Multituberculata

Multituberculata (commonly known as multituberculates, named for the multiple tubercles of their teeth) is an extinct order of rodent-like mammals with a fossil record spanning over 130 million years.

[2][3] Multituberculates are usually placed as crown mammals outside either of the two main groups of living mammals—Theria, including placentals and marsupials, and Monotremata[4]—but usually as closer to Theria than to monotremes.

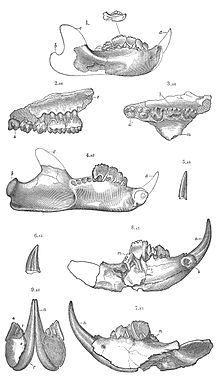

The multituberculates had a cranial and dental anatomy superficially similar to rodents such as mice and rats, with cheek-teeth separated from the chisel-like front teeth by a wide tooth-less gap (the diasteme).

[citation needed] Unlike rodents, which have ever-growing teeth, multituberculates underwent dental replacement patterns typical of most mammals (though in at least some species the lower incisors continued to erupt long after the root's closure).

[4][7] Palinal jaw strokes are almost entirely absent in modern mammals (with the possible exception of the dugong[11]), but are also present in haramiyidans, argyrolagoideans and tritylodontids, the former historically united with multituberculates on that basis.

Multituberculate mastication is thought to have operated in a two stroke cycle: first, food held in place by the last upper premolar was sliced by the bladelike lower pre-molars as the dentary moved orthally (upward).

[4][7] The structure of the pelvis in the Multituberculata suggests that they gave birth to tiny helpless, underdeveloped young, similar to modern marsupials, such as kangaroos.

[16] Multituberculates first appear in the fossil record during the Jurassic period, and then survived and even dominated for over one hundred million years, longer than any other order of mammaliforms, including placental mammals.

[17] During the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, primitive multituberculates, collectively grouped into the paraphyletic "Plagiaulacida", were abundant and widespread across Laurasia (including Europe, Asia and North America).

Thanks to the well-preserved Ptilodus specimens found in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, we know that these multituberculates were able to abduct and adduct their big toes, and thus that their foot mobility was similar to that of modern squirrels, which descend trees head first.

[citation needed] Suborder †Plagiaulacida Simpson 1925 Source:[29] Paulchoffatiidae Plagiaulacidae Eobaataridae Ferugliotheriidae Groeberiidae Sudamericidae Cimolodontidae Ptilodontoidea Cimexomys Cimolomyidae Boffius Buginbaatar Eucosmodontidae Microcosmodontidae Bulganbaatar Chulsanbaatar Sloanbaataridae Nemegtbaatar Djadochtatheriidae Kogaionidae Yubaatar Bubodens Valenopsalis Lambdopsalidae Taeniolabididae Multituberculates are some of the earliest mammals to display complex social behaviours.

For one thing, it relies on the assumption that these mammals are "inferior" to more derived placentals, and ignores the fact that rodents and multituberculates had co-existed for at least 15 million years.

This combination of factors suggests that, rather than gradually declining due to pressure from rodents and similar placentals, multituberculates simply could not cope with climatic and vegetation changes, as well as the rise of new predatory eutherians, such as miacids.

As a whole, it seems that Asian multituberculates, unlike North American and European species, never recovered from the KT event, which allowed the evolution and propagation of rodents in the first place.