Murabaha

Murabaḥah, murabaḥa, or murâbaḥah (Arabic: مرابحة, derived from ribh Arabic: ربح, meaning profit) was originally a term of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) for a sales contract where the buyer and seller agree on the markup (profit) or "cost-plus" price[1] for the item(s) being sold.

Murabaha financing is basically the same as a rent-to-own arrangement in the non-Muslim world, with the intermediary (e.g., the lending bank) retaining ownership of the item being sold until the loan is paid in full.

[4] The purpose of murabaha is to finance a purchase without involving interest payments, which most Muslims (particularly most scholars) consider riba (usury) and thus haram (forbidden).

The buyer/borrower pays the seller/lender at an agreed-upon higher price; instead of interest charges, the seller/lender makes a religiously permissible "profit on the sale of goods".

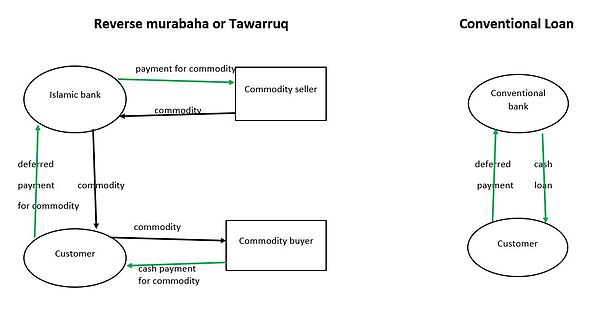

"[16][19] Critics/skeptics complain/note that in practice most "murabaḥah" transactions are merely cash-flows between banks, brokers, and borrowers, with no buying or selling of commodities;[20] that the profit or markup is based on the prevailing interest rate used in haram lending by the non-Muslim world;[21] that "the financial outlook" of Islamic murabaha financing and conventional debt/loan financing is "the same",[22] as is most everything else besides the terminology used.

Another scholar, M.O.Farooq, states "it is well-known and supported by many hadiths that the Prophet had entered into credit-purchase transactions (nasi'ah) and also that he paid more than the original amount" in his repayment.

[25] Murabahah and related fixed financing has been approved by a number of government reports in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan on how to eliminate Interest.

[36] According to one source (Mushtak Parker), Islamic financial institutions "have long tried to grapple with the issue of delayed payments or defaults, but thus far there is no universal consensus across jurisdictions in this respect.

"[35]) In its 1980 Report on the Elimination of Interest from the Economy,[37] the Council of Islamic Ideology of Pakistan stated that murabahah should Murâbaḥah is one of three types of bayu-al-amanah (fiduciary sale), requiring an "honest declaration of cost".

[W]here direct purchase from the supplier is not practicable for some reason, it is also allowed that he makes the customer himself his agent to buy the commodity on his behalf.

[39]The idea that the seller may not use murâbaḥah if profit-sharing modes of financing such as mudarabah or musharakah are practicable, is supported by other scholars that those in the Council of Islamic Ideology.

"[42] A number of economists have noted the dominance of murabahah in Islamic finance, despite its theological inferiority to profit and loss sharing.

Reportedly the most popular mode of Islamic financing is cost-plus murabaha in a credit sale setting (Bay bithaman 'ajil) with "an added binding promise on the customer to purchase the property, thus replicating secured lending in `Shari'a compliant` manner."

The concept was developed by Sami Humud, and shortly after it became popular Islamic Banking began its strong growth in the late 1970s.

While this is not "preferable" from a Sharia point of view, it avoids extra cost and the problem of a financial institution lacking the expertise to identify the exact or best product or the ability to negotiate a good price.

[53] It was used by a number of modern Islamic financial institutions despite condemnation by jurists, but in recent years its use is "very much limited" according to Harris Irfan.

According to Islamic banker Harris Irfan, this complication has "not persuaded the majority of scholars that this series of transactions is valid in the Sharia.

[67][68] Orthodox Islamic Scholars such as Taqi Usmani emphasize that murâbaḥah should only be used as a structure of last resort where profit and loss sharing instruments are unavailable.

[25] Usmani himself describes murâbaḥah as a "borderline transaction" with "very fine lines of distinction" compared to an interest bearing loan, as "susceptible to misuse", and "not an ideal way of financing".

[21]Another pioneer, Mohammad Najatuallah Siddiqui, has lamented that "as a result of diverting most of its funds towards murabaha, Islamic financial institutions may be failing in their expected role of mobilizing resources for development of the countries and communities they are serving,"[69] and even bringing about "a crisis of identity of the Islamic financial movement.

[20] Frank Vogel and Samuel Hayes also note multi-billion-dollar murabaha transactions in London "popular for many years", where "many doubt the banks truly assume possession, even constructively, of inventory".

[35][36][Note 9] According to Ibrahim Warde, Islamic banks face a serious problem with late payments, not to speak of outright defaults, since some people take advantage of every dilatory legal and religious device ...

As a result, 'debtors know that they can pay Islamic banks last since doing so involves no cost'[81][83] Warde also complains that "Many businessmen who had borrowed large amounts of money over long periods of time seized the opportunity of Islamicization to do away with accumulated interest of their debt, by repaying only the principal -- usually a puny sum when years of double-digit inflation were taken into consideration.

But regulatory frameworks in most countries forbid financial intermediaries such as banks "from owning or trading real properties" (according to scholar Mahmud El-Gamal).

To avoid these dangers SPVs (Special Purpose Vehicles) are created to hold title to the property and also "serve as parties to various agreements regarding obligations for repairs and insurance" as required by Islamic jurists.

Another argument that murahaba is shariah compliant is that it is made up of two transactions, both halal (permissible): Buying a car for $10,000 and selling it for $12,000 is allowed by Islam.

The fact that no penalties are assessed if Adam is delinquent on his payments simply means that the amount of interest in the murabaha contract is fixed at $2,000.