Murder of William de Cantilupe

The murder of Sir William de Cantilupe, who was born around 1345, by members of his household, took place in Scotton, Lincolnshire, in March 1375.

The family was a long-established and influential one in the county; de Cantilupes traditionally provided officials to the Crown both in central government and at the local level.

The chief suspects were two neighbours—a local knight, Ralph Paynel; and the sheriff, Sir Thomas Kydale—as well as de Cantilupe's entire household, particularly his wife Maud, the cook and a squire.

[3] The family had traditionally played an important role in both local society and central government[4] with a history of loyal and diligent service to the crown.

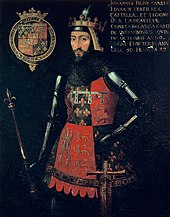

[2] William de Cantilupe, 30 years old at the time of his death,[8] was a "knight of some stature" in the region, notes the historian J. G. Bellamy,[9] and by then had been retained by John of Gaunt.

[14][15] A later jury established that de Cantilupe was "at peace with God and the lord king", and Pedersen has taken this to indicate that he had prayed, and, therefore, was about to retire for the night.

[22]The attempt to foist guilt upon highwaymen was a piece of cool calculation and the dressing up of William's body while rigor mortis set in shows a cold-blooded attitude to the job which would be impressive were it not so horrific.

[19] Four members of the household were later alleged to have sought refuge with Sir Ralph Paynel, whose manor was 90 miles (140 km) south of Scotton.

The medievalist Rosamund Sillem has identified Paynel as the conspiracy's mastermind,[30] for example, while Pedersen has argued that "there is a strong circumstantial case to be made that they were acting under the direction of William's wife, Maud Nevil".

Sillem suggests that this may be explained by the fact that, by the time they came to consider the evidence, they could only rely on memories to an event which occurred at least six months previously.

[39] Maud and de Cletham were released on a bond of mainprise on the charges of aiding and abetting those other principals who had failed to appear.

[note 18] Paynel was charged with harbouring Maud, Lovel, Gyse and Cooke[9][16] on his Caythorpe manor, and also released on mainprise until Michaelmas the following year.

[22] One of Kydale's duties as sheriff was to select the juries that sat on the case, and by extension, that would decide Maud's guilt or innocence.

On Monday 27 August 1375[13] she escaped the immediate dispensing of justice by bribing her gaolers in Lincoln Castle, where she had been imprisoned awaiting trial.

[44][note 22] The castle bailiffs, Thomas Thornhaugh and John Bate, were later arrested and tried for allowing Agatha to escape justice.

[44][note 23] Cooke and Gyse were charged of having with sedicioni precogitale ... interfecerunt et murdraverunt ("sedition aforethought ... killed and murdered") their master.

Pedersen suggests they may have been promised a form of insurance by their social betters against capture and conviction, or that if that occurred, they would be treated leniently and their families "looked after in case [Gyse and Cooke] were not able to flee the country".

[51] De Cantilupe had been serving abroad in the years before his death, and it is possible that Maud and Kydale had begun a relationship in his absence.

Regarding Ralph Paynel, for example: The literature has accepted that he probably played a crucial role in the murder, and that he was pivotal in ensuring that most of the persons involved in the crime avoided the censure of the law.

[54]Paynel "was no doubt acutely aware of the multitude of insults he had received at the hands of the de Cantilupes",[2] which went back to at least 1368.

Others escaped, either through complicated manipulation of the law and jury rigging—for example Maud, Kydale and Ralph—or simpler, more traditional methods, such as Agatha's prison break.

[9] Bellamy suggests that the reason the household workers ran away in the first place was probably down to the infamy the case had engendered, as a direct result of which, he says, "juries were more likely than usual to find the accused guilty".

[16] Not only had it effectively ended a family which, in Sillem's words, had "played a considerable part in English history",[68] but the killing of a man by either his servants or his wife—or both—"was regarded as particularly heinous by all ranks of society".

[note 33] The medievalist Carol Rawcliffe suggests that "whatever apprehensions Bussy may have felt in following the short-lived Kydale as her third husband were clearly overcome by the prospect of a greatly increased rent-roll".

In what Sillem calls a "curious exception" to the unknown fates of most of those who had been outlawed, at the supplication of Queen Anne in 1387, King Richard pardoned John Tailour of Barneby, Cantilupe's steward.

[note 35] She highlighted how the case not only demonstrated contemporary approaches to crime and petty treason but also provided a wealth of information on the more mundane aspects of society, such as the organisation of a late-14th century magnatial household.

[22] Platts has compared the killing of de Cantilupe to the "kind of plotting in which Shakespeare's audiences revelled" two and a half centuries later,[16] while Bellamy suggests it "contained elements of the modern murder drama".

[9] Not least, argues Bellamy, because of the transporting of the corpse and the attempt at blaming highwaymen, elements of crime which "are rarely found in medieval records".

[35][note 38] Pedersen suggests that not only was de Cantilupe's murder cleverly planned over a long period, "it also bears all the hallmarks of ... having been put on hold until everybody was in positions of power where they could cover for each other.

When Richard Pope and William del Idle slew their master John Coventry, his wife Elena set a standard of spousal rectitude that is singled out for approving mention, promptly pursuing the fleeing murderers through four neighboring villages and beyond.