Apostasy in Islam

[14][15][16][17] Until the late 19th century, the majority of Sunni and Shia jurists held the view that for adult men, apostasy from Islam was a crime as well as a sin, punishable by the death penalty,[3][18] but with a number of options for leniency (such as a waiting period to allow time for repentance[3][19][20][21] or enforcement only in cases involving politics),[22][23][24] depending on the era, the legal standards and the school of law.

The Quran references apostasy[49] (2:108, 66; 10:73; 3:90; 4:89, 137; 5:54; 9:11–12, 66; 16:06; 88:22–24) in the context of attitudes associated with impending punishment, divine anger, and the rejection of repentance for individuals who commit this act.

"Other hadith give differing statements about the fate of apostates;[36][67] that they were spared execution by repenting, by dying of natural causes or by leaving their community (the last case sometimes cited as an example of open apostasy that was left unpunished).

'The argument has been made (by the Fiqh Council of North America, among others) that the hadiths above – traditionally cited as proof that apostates from Islam should be punished by death – have been misunderstood.

(In the words of Frank Griffel) these are: Three centuries later, Al-Ghazali wrote that one group, known as "secret apostates" or "permanent unbelievers" (aka zandaqa), should not be given a chance to repent, eliminating Al-Shafi'i's third condition for them although his view was not accepted by his Shafi'i madhhab.

"[94][95] Historian Bernard Lewis writes that in "religious polemic" of early Islamic times, it was common for one scholar to accuse another of apostasy, but attempts to bring an alleged apostate to justice (have them executed) were very rare.

Al-Ghazali "is often credited with having persuaded theologians", in his Fayal al-tafriqa, "that takfir is not a fruitful path and that utmost caution is to taken in applying it", but in other writing, he made sure to condemn as beyond the pale of Islam "philosophers and Ismaili esotericists".

[101] There is general agreement among Muslims that the takfir and mass killings of alleged apostates perpetrated not only by ISIL but also by the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's jihadis[82] were wrong, but there is less unanimity in other cases, such as what to do in a situation where self-professed Muslim(s) – post-modernist academic Nasr Abu Zayd or the Ahmadiyya movement – disagree with their accusers on an important doctrinal point.

[104] The three types (conversion, blasphemy and heresy) of apostasy may overlap – for example some "heretics" were alleged not to be actual self-professed Muslims, but (secret) members of another religion, seeking to destroy Islam from within.

(Abdullah ibn Mayun al-Qaddah, for example, "fathered the whole complex development of the Ismaili religion and organisation up to Fatimid times," was accused by his different detractors of being (variously) "a Jew, a Bardesanian and most commonly as an Iranian dualist")[105] In Islamic literature, the term "blasphemy" sometimes also overlaps with kufr ("unbelief"), fisq (depravity), isa'ah (insult), and ridda (apostasy).

[39] Still others support a "centrist or moderate position" of executing only those whose apostasy is "unambiguously provable" such as if two just Muslim eyewitnesses testify; and/or reserving the death penalty for those who make their apostacy public.

[126] Traditional Sunnī and Shīʿa Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) and their respective schools (maḏāhib) agree on some issues – that male apostates should be executed, and that most but not all perpetrators should not be given a chance to repent; among the excluded are those who practice sorcery (subhar), treacherous heretics (zanādiqa), and "recidivists".

[140] "The vast majority of Muslim scholars both past as well as present" consider apostasy "a crime deserving the death penalty", according to Abdul Rashided Omar, writing circa 2007.

At least some conservative jurists and preachers have attempted to reconcile following the traditional doctrine of death for apostasy while addressing the principle of freedom of religion.

[216] Shias believe ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib is the true successor to Muhammad, while Sunnis consider Abu Bakr to hold that position.

[26] According to historian Bernard Lewis, in "religious polemic" in the "early times" of Islam, "charges of apostasy were not unusual", but the accused were seldom prosecuted, and "some even held high offices in the Muslim state".

[96] Another source, legal historian Sadakat Kadri, argues execution was rare because "it was widely believed" that any accused apostate "who repented by articulating the shahada [...] had to be forgiven" and their punishment delayed until after Judgement Day.

However, he also states that prior to 11th century execution seems rare he gives an example of a Jew who had converted to Islam and used the threat of reverting to Judaism in order to gain better treatment and privilege.

[230] Zindīq (often a "blanket phrase" for "intellectuals" under suspicion of having abandoned Islam" or freethinker, atheist or heretic who conceal their religion),[231] experienced a wave of persecutions from 779 to 786.

A history of those times states:[229] "Tolerance is laudable", the Spiller (the Caliph Abu al-Abbās) had once said, "except in matters dangerous to religious beliefs, or to the Sovereign's dignity.

He was the first Caliph to order composition of polemical works to in refutation of Freethinkers and other heretics; and for years he tried to exterminate them absolutely, hunting them down throughout all provinces and putting accused persons to death on mere suspicion.

"[232]) In 12th-century Iran, al-Suhrawardi along with followers of Ismaili sect of Islam were killed on charges of being apostates;[53] in 14th-century Syria, Ibn Taymiyyah declared Central Asian Turko-Mongol Muslims as apostates due to the invasion of Ghazan Khan;[233] in 17th-century India, Dara Shikoh and other sons of Shah Jahan were captured and executed on charges of apostasy from Islam by his brother Aurangzeb although historians agree it was more political than a religious execution.

[citation needed] British envoy to the court of Sultan Abdulmejid I (1839–1861), Stratford Canning, led diplomatic representatives from Austria, Russia, Prussia, and France in a "tug of war" with the Ottoman government.

[235] In the end (following the execution of the Armenian), the Sublime Porte agreed to allow "complete freedom of Christian missionaries" to try to convert Muslims in the Empire.

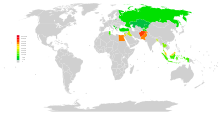

[254] As of 2014, apostasy was a capital offense in Afghanistan, Brunei, Mauritania, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

For example, the Christian organisation Barnabas Fund reports: The field of apostasy and blasphemy and related "crimes" is thus obviously a complex syndrome within all Muslim societies which touches a raw nerve and always arouses great emotional outbursts against the perceived acts of treason, betrayal and attacks on Islam and its honour.

[266] Writing in 2015, Ahmed Benchemsi argued that while Westerners have great difficulty even conceiving of the existence of an Arab atheist, "a generational dynamic" is underway with "large numbers" of young people brought up as Muslims "tilting away from ... rote religiosity" after having "personal doubts" about the "illogicalities" of the Quran and Sunnah.

[267] Immigrant apostates from Islam in Western countries "converting" to Atheism have often gathered for comfort in groups such as Women in Secularism, Ex-Muslims of North America, Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain,[268] sharing tales of the tension and anxieties of "leaving a close-knit belief-based community" and confronting "parental disappointment", "rejection by friends and relatives", and charges of "trying to assimilate into a Western culture that despises them", often using terminology first uttered by the LGBT community – "'coming out,' and leaving 'the closet'".

[267]A survey based on face-to-face interviews conducted in 80 languages by the Pew Research Center between 2008 and 2012 among thousands of Muslims in many countries, found varied views on the death penalty for those who leave Islam to become an atheist or to convert to another religion.

[32] The Governments of the Gulf Cooperation Council (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait) did not permit Pew Research to survey nationwide public opinion on apostasy in 2010 or 2012.