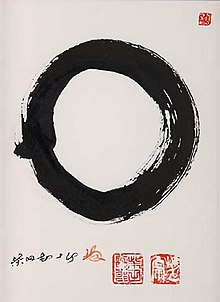

No-mind

Likewise, in Sanskrit, the term is a compound of the prefix a- (for negation) and the word citta (mind, thought, consciousness, heart).

[10] Another similar Sanskrit term is amanasikāra (non-thinking, mental non-engagement), which is found in the works of the 11th century tantric yogi Maitripa.

Suzuki see the term wu-nien (無念, without thought, without recollection, with nien possibly rendering smṛti, "mindfulness") as being synonymous to wu-xin.

[2] Regarding terms which negate "vikalpa" (conceptualization, discrimination, imagination), such as avikalpa and nirvikalpa, these are also widely used in Buddhist sources.

"[18] The Aṣṭasāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā sutra even equates the two, stating: "the non-perception (anupalambha) of all principles (dharmas) is called the perfection of wisdom".

The Sanskrit term acitta (no-mind, no-thought, unconceived, inconceivable, from a+citta) is found in several Mahayana sutras, and it is often related to an absence of conceptualization (vikalpa), clinging and negative mental states or thoughts.

When the mind is neither associated with nor dissociated from greed, hatred, delusion, proclivities (anusaya), fetters (samyojana), or false views (drsti), then this constitutes its luminosity.

The state of no-mind, which is immutable (avikra) and undifferentiated (avikalpa), constitutes the ultimate reality (dharmata) of all dharmas [phenomena].

[21] The term also appears in the Gaganagañjaparipṛcchā sutra, which states:Strive for awakening (bodhi) freed from false view (darśana), and for essential nature (svabhāva) which is like an illusion (māya) and mirage (marīci).

[24]In his commentary on this passage, the later Indian philosopher Sthiramati states that this kind of supramundane knowledge refers to a non-discriminative experience beyond subject-object duality.

[25] The term no-mind (wu-xin) is also found in the Zhuangzi as well as in the commentary of Guo Xiang, as was thus also discussed by Chinese Daoist thinkers.

As such, many scholars like Fukunaga Mitsuji have suggested that this Daoist idea also influenced the Chinese Buddhist understanding of no-mind.

[26][27] It is a state of being carefree and ease which the sage has achieved through the pursuit of Daoist self-cultivation practices such as fasting the mind (心齋, xīn zhāi) and sitting and forgetting (坐忘; zuòwàng).

If, for one thought-moment, there is a break, the dharma-body separates from the physical body, and in the midst of successive thoughts there will be no attachment to any kind of matter.

It is the key topic of a short Chan text from Dunghuang called Treatise on No-Mind (Wuxinlun) which is attributed to Bodhidharma.

[30] Likewise, Huangbo Xiyun (died 850 CE) mentions the concept several times, writing that "if one could only achieve no-mind right at this moment, the fundamental essence (本体) will appear of itself".

Analogously, the perceptions of seeing and hearing, just like the film that creates the illusion for diseased eyes, cause the errors and delusions of all sentient beings.

[1] Likewise, Japanese philosopher Izutsu Toshihiko argues that no-mind is not unconsciousness, mental torpor, lethargy or absent-mindedness.

When the Ch'an writers talk about no-thought, or no-mind, it is this state of non-clinging or freedom from mistaken conceptualization to which they are referring, rather than the permanent cessation of thinking that some imagine.

In this context, the Zen student trains to live in the state of no-mind in every aspect of their daily routine, eventually achieving a kind of effortlessness in all activities.

[36]This passage is actually based on a traditional zen dialogue about master Yakusan Gudo (Chinese: Yueh-shan Hung-tao c. 745-828) which also contains phrases like non-thinking.

[38] According to Dogen scholar Masanobu Takahashi, the term hishiryō is not a state in which there is no mental activity whatsoever nor a cutting off of all thinking.

Instead, it refers to a state "beyond thinking and not-thinking" which Thomas Kasulis glosses as "merely accepting the presence of ideation without either affirmation or denial.

[39] Kasulis understands the term phenomenologically as "pure presence of things as they are", "without affirming nor negating", without accepting nor rejecting, without believing nor disbelieving.

[40] Similarly, Hee-Jin Kim describes this state as "not just to transcend both thinking and not-thinking, but to realize both, in the absolutely simple and singular act of resolute sitting itself", which is "objectless, subjectless, formless, goalless and purposeless" and yet it is not "void of intellectual content as in a vacuum".

He wrote an influential letter to a master swordsman, Yagyū Munenori, called The Mysterious Record of Immovable Wisdom.

[44] On page 84 of his 1979 book Zen in the Martial Arts, Joe Hyams wrote that Bruce Lee had read the following quote to him, attributed to the legendary Zen master Takuan Sōhō:[45] The mind must always be in the state of 'flowing,' for when it stops anywhere that means the flow is interrupted and it is this interruption that is injurious to the well-being of the mind.

Many martial artists train to achieve this state of mind during kata so that a flawless execution of moves is learned and may be repeated at any other time.

[12] Suzuki held that a key aspect of no-mind was “receptivity” (judōsei 受動性), a state of acceptance, openness, letting go, and non-resistance.

"[48] For Suzuki, the attainment of no-mind is achieved through entrusting oneself to the Buddha, which is the “original purity” (honshō shōjō 本性清浄) at heart of all beings.