Medieval music

Polyphonic genres, in which multiple independent melodic lines are performed simultaneously, began to develop during the high medieval era, becoming prevalent by the later 13th and early 14th century.

The development of polyphonic forms is often associated with the Ars antiqua style associated with Notre-Dame de Paris, but improvised polyphony around chant lines predated this.

The principles of this kind of organum date back at least to an anonymous 9th century tract, the Musica enchiriadis, which describes the tradition of duplicating a preexisting plainchant in parallel motion at the interval of an octave, a fifth or a fourth.

[5] While most early motets were sacred and may have been liturgical (designed for use in a church service), by the end of the thirteenth century the genre had expanded to include secular topics, such as political satire and courtly love, and French as well as Latin texts.

The madrigal form also gave rise to polyphonic canons (songs in which multiple singers sing the same melody, but starting at different times), especially in Italy where they were called caccie.

[12] As Rome tried to centralize the various liturgies and establish the Roman rite as the primary church tradition the need to transmit these chant melodies across vast distances effectively was equally glaring.

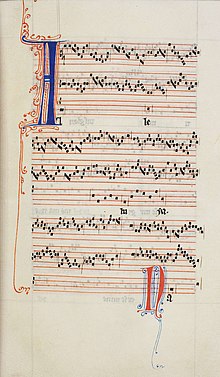

The first step to fix this problem came with the introduction of various signs written above the chant texts to indicate direction of pitch movement, called neumes.

[12] The origin of neumes is unclear and subject to some debate; however, most scholars agree that their closest ancestors are the classic Greek and Roman grammatical signs that indicated important points of declamation by recording the rise and fall of the voice.

In contrast, the Ars Nova period introduced two important changes: the first was an even smaller subdivision of notes (semibreves, could now be divided into minim), and the second was the development of "mensuration."

Many scholars, citing a lack of positive attributory evidence, now consider "Vitry's" treatise to be anonymous, but this does not diminish its importance for the history of rhythmic notation.

In his work he describes three defining elements to each mode: the final (or finalis), the reciting tone (tenor or confinalis), and the range (or ambitus).

Around the end of the 9th century, singers in monasteries such as St. Gall in Switzerland began experimenting with adding another part to the chant, generally a voice in parallel motion, singing mostly in perfect fourths or fifths above the original tune (see interval).

Later developments of organum occurred in England, where the interval of the third was particularly favoured, and where organa were likely improvised against an existing chant melody, and at Notre Dame in Paris, which was to be the centre of musical creative activity throughout the thirteenth century.

Surviving manuscripts from this period include the Musica Enchiriadis, Codex Calixtinus of Santiago de Compostela, the Magnus Liber, and the Winchester Troper.

[citation needed] Many have been preserved sufficiently to allow modern reconstruction and performance (for example the Play of Daniel, which has been recently recorded at least ten times).

The clausula, thus practised, became the motet when troped with non-liturgical words, and this further developed into a form of great elaboration, sophistication and subtlety in the fourteenth century, the period of Ars nova.

[57] The increasing rhythmic complexity seen in Petronian motets would be a fundamental characteristic of the 14th century, though music in France, Italy, and England would take quite different paths during that time.

[citation needed] The Cantigas de Santa Maria ("Canticles of St. Mary") are 420 poems with musical notation, written in Galician-Portuguese during the reign of Alfonso X The Wise (1221–1284).

The music of the troubadours and trouvères was a vernacular tradition of monophonic secular song, probably accompanied by instruments, sung by professional, occasionally itinerant, musicians who were as skilled as poets as they were singers and instrumentalists.

The period of the troubadours wound down after the Albigensian Crusade, the fierce campaign by Pope Innocent III to eliminate the Cathar heresy (and northern barons' desire to appropriate the wealth of the south).

The Galician-Portuguese school, which was influenced to some extent (mainly in certain formal aspects) by the Occitan troubadours, is first documented at the end of the twelfth century and lasted until the middle of the fourteenth.

The term "Ars nova" (new art, or new technique) was coined by Philippe de Vitry in his treatise of that name (probably written in 1322), in order to distinguish the practice from the music of the immediately preceding age.

This tradition started around mid-century with isolated or paired settings of Kyries, Glorias, etc., but Machaut composed what is thought to be the first complete mass conceived as one composition.

The Geisslerlieder were the songs of wandering bands of flagellants, who sought to appease the wrath of an angry God by penitential music accompanied by mortification of their bodies.

Already discussed under Ars Nova has been the practice of isorhythm, which continued to develop through late-century and in fact did not achieve its highest degree of sophistication until early in the 15th century.

The term "mannerism" was applied by later scholars, as it often is, in response to an impression of sophistication being practised for its own sake, a malady which some authors have felt infected the Ars subtilior.

While the music of the fourteenth century is fairly obviously medieval in conception, the music of the early fifteenth century is often conceived as belonging to a transitional period, not only retaining some of the ideals of the end of the Middle Ages (such as a type of polyphonic writing in which the parts differ widely from each other in character, as each has its specific textural function), but also showing some of the characteristic traits of the Renaissance (such as the increasingly international style developing through the diffusion of Franco-Flemish musicians throughout Europe, and in terms of texture an increasing equality of parts).

[citation needed] English stylistic tendencies in this regard had come to fruition and began to influence continental composers as early as the 1420s, as can be seen in works of the young Dufay, among others.

He was the most famous member of the Franco-Flemish School in the last half of the 15th century, and is often considered[weasel words] the most influential composer between Dufay and Josquin des Prez.

A strong influence on Josquin des Prez and the subsequent generation of Netherlanders, Ockeghem was famous throughout Europe Charles VII for his expressive music, although he was equally renowned for his technical prowess.