Nabataean art

They are known for finely-potted painted ceramics, which became dispersed among Greco-Roman world, as well as contributions to sculpture and Nabataean architecture.

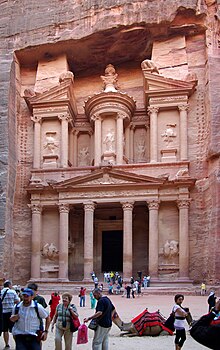

Nabataean art is most well known for the archaeological sites in Petra, specifically monuments such as Al Khazneh and Ad Deir.

[3] These vessels would have been for daily use, not ceremonial, despite the unusually large amount of broken shards found in rubbish heaps.

Some offer features of clear Greek influence, such as pediments, metope and triglyph entablatrures, and capitals.

These tombs are simple in style but elaborated in function, often featuring steps, platforms, libation holes, cisterns, water channels and sometimes banqueting halls.

Many feature numerous religious icons, inscriptions, and sanctuaries found in association with springs, catchment pools, and channels.

Later, under Achaemenid Persians, the fortification context was removed, giving a greater scope to a sign of kingship and authority.

Obelisks are a narrow tapering monument, often used to represent the Nephesh, specific leaders, and gods of monolithic societies.

The Urn Tomb is built high on the mountain side, and requires climbing up a number of flights of stairs.

[5] Feasts dedicated to the dead were held in the area of Petra in triclinia set up in man-made caves, which in special cases were part of large, elaborate complexes, such as the one in Wadi Farasa.

Wild hair, dramatic facial expressions, and S-curves mirrored the Hellenistic style of sculpture.

Greek sculpture was represented with the long, tight beards, symmetry, and perfecting of the human body.

The majority are gods and goddesses that were worshiped by the Nabataeans; however, some are representative of Greek, Roman, and Middle Eastern beliefs.

The carvings are rectangular and non-figural, though in some cases they have stylised eyes and a nose, similar to Aramic and South Arabian face stelae.

[11] In 2010, it was revealed that a biclinium, now known colloquially as the Painted House, at Little Petra in Jordan had extensive ceiling frescoes, which had long been concealed under soot from Bedouin campfires, and other inscriptions in the ensuing centuries.

They depict, in extensive detail and with a variety of media, including glazes and gold leaf, imagery such as grapevines and putti associated with the Greek god Dionysus, suggesting the space may have been used for wine consumption, perhaps with visiting merchants.