Hindu temple architecture

[1] Hindu temple architecture reflects a synthesis of arts, the ideals of dharma, values, and the way of life cherished under Hinduism.

[2] The form and meanings of architectural elements in a Hindu temple are designed to function as a place in which to create a link between man and the divine, to help his progress to spiritual knowledge and truth, his liberation it calls moksha.

Aspects seen on Buddhist architecture like the stupa may have been influenced by the shikhara, a stylistic element which in some regions evolved to the pagoda which are seen throughout Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal, China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

[18][20] Though there are very few remains of stone Hindu temples before the Gupta dynasty in the 5th century CE, there may be earlier structures constructed from timber-based architecture.

The rock-cut Udayagiri Caves (401 CE) are among the most important early sites, built with royal sponsorship, recorded by inscriptions, and with impressive sculpture.

According to Meister, the Mahabalipuram temples are "monolithic models of a variety of formal structures all of which already can be said to typify a developed "Dravida" (South Indian) order".

[31] Possibly the oldest Hindu temples in Southeast Asia dates back to 2nd century BCE from the Funan site of Oc Eo in the Mekong Delta.

[41][note 1] Prior to the 14th-century local versions of Hindu temples were built in Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

[49][50] At the centre of the temple, typically below and sometimes above or next to the deity, is mere hollow space with no decoration, symbolically representing Purusa, the Supreme Principle, the sacred Universal, one without form, which is present everywhere, connects everything, and is the essence of everyone.

The appropriate site for a Mandir, suggest ancient Sanskrit texts, is near water and gardens, where lotus and flowers bloom, where swans, ducks and other birds are heard, where animals rest without fear of injury or harm.

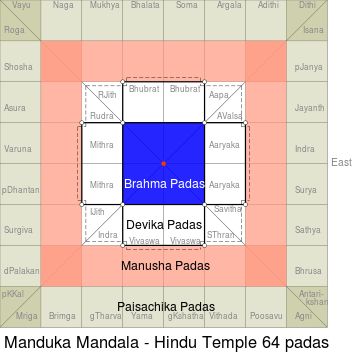

[54] The design lays out a Hindu temple in a symmetrical, self-repeating structure derived from central beliefs, myths, cardinality and mathematical principles.

[2] Scholars such as Lewandowski state that this shape is inspired by cosmic mountain of Mount Meru or Himalayan Kailasa, the abode of gods according to its ancient mythology.

[2] In some temples, these images or wall reliefs may be stories from Hindu Epics, in others they may be Vedic tales about right and wrong or virtues and vice, in some they may be idols of minor or regional deities.

Michael Meister states that these exceptions mean the ancient Sanskrit manuals for temple building were guidelines, and Hinduism permitted its artisans flexibility in expression and aesthetic independence.

[6] The Hindu text Sthapatya Veda describes many plans and styles of temples of which the following are found in other derivative literature: Chaturasra (square), Ashtasra (octagonal), Vritta (circular), Ayatasra (rectangular), Ayata Ashtasra (rectangular-octagonal fusion), Ayata Vritta (elliptical), Hasti Prishta (apsidal), Dvayasra Vrita (rectangular-circular fusion); in Tamil literature, the Prana Vikara (shaped like a Tamil Om sign, ) is also found.

[62] The guilds covered almost every aspect of life in the camps around the site where the workmen lived during the period of construction, which in the case of large projects might be several years.

[65] This "presumably reflected the influence of Brahman theologians" states Michell, and the "increasing dependence of the artist upon the brahmins" on suitable forms of sacred images.

[70] Some scholars have questioned the relevance of these texts, whether the artists relied on śilpa śāstras theory and Sanskrit construction manuals probably written by Brahmins, and did these treatises precede or follow the big temples and ancient sculptures therein.

Other scholars question whether big temples and complex symmetric architecture or sculpture with consistent themes and common iconography across distant sites, over many centuries, could have been built by artists and architects without adequate theory, shared terminology and tools, and if so how.

[71] According to George Michell – an art historian and professor specializing in Hindu Architecture, the theory and the creative field practice likely co-evolved, and the construction workers and artists building complex temples likely consulted the theoreticians when they needed to.

[65] The ancient Hindu texts on architecture such as Brihatsamhita and others, states Michell, classify temples into five orders based on their typological features: Nagara, Dravida, Vesara, ellipse and rectangle.

In some regions, such as in South Karnataka, the local availability of soft stone led to Hoysala architects to innovate architectural styles that are difficult with hard crystalline rocks.

Hindu temple architecture has historically been affected by the building material available in each region, its "tonal value, texture and structural possibilities" states Michell.

There are numerous other distinct features such as the dvarapalakas – twin guardians at the main entrance and the inner sanctum of the temple and goshtams – deities carved in niches on the outer side walls of the garbhagriha.

Mentioned as one of three styles of temple building in the ancient book Vastu shastra, the majority of the existing structures are located in the Southern Indian states of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, some parts of Maharashtra, Odisha and Sri Lanka.

For example, the rainy climate and the materials of construction available in Bengal, Kerala, Java and Bali Indonesia have influenced the evolutions of styles and structures in these regions.

Between 500 and 757 CE, Badami Chalukyas built Hindu temples out of sandstone cut into enormous blocks from the outcrops in the chains of the Kaladgi hills.

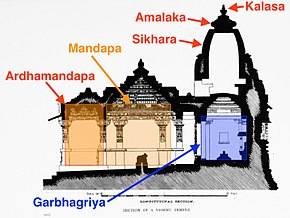

Subsequently, the design, plan and layout of the temple follows the rule of space allocation within three elements; commonly identified as foot (base), body (centre), and head (roof).

The main superstructure of typical Khmer temple is a towering prasat called prang which houses the garbhagriha inner chamber, where the murti of Vishnu or Shiva, or a lingam resides.

Khmer temples were typically enclosed by a concentric series of walls, with the central sanctuary in the middle; this arrangement represented the mountain ranges surrounding Mount Meru, the mythical home of the gods.