Nahuas

They have also been called Mēxihcatl [meːˈʃiʔkat͡ɬ] (singular), Mēxihcah [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ] (plural)[15] or in Spanish Mexicano(s) [mexiˈkano(s)] "Mexicans", after the Mexica, the Nahua tribe which founded the Aztec Empire.

[23] The largest concentrations of Nahuatl speakers are found in the states of Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, and Guerrero.

Significant populations are also found in México State, Morelos, and the Mexican Federal District, with smaller communities in Michoacán and Durango.

The modern influx of Mexican workers and families into the United States has resulted in the establishment of a few small Nahuatl-speaking communities, particularly in Texas, New York and California.

[43] Classical Nahuatl was a lingua franca in Central Mexico before the Spanish conquest due to Aztec hegemony,[44] and its role was not only preserved but expanded in the initial stage of colonial rule, encouraged by the Spaniards as a literary language and tool to convert diverse Mesoamerican peoples.

[45] Nahua populations in Mexico are centered in the middle of the country, with most speakers in the states of Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Guerrero and San Luis Potosí.

[49] From c. 600 CE the Nahua quickly rose to power in central Mexico and expanded into areas earlier occupied by Oto-Manguean, Totonacan and Huastec peoples.

Around 1000 CE the Toltec people, normally assumed to have been of Nahua ethnicity, established dominion over much of central Mexico which they ruled from Tollan Xicocotitlan.

After the fall of the Toltecs a period of large population movements followed and some Nahua groups such as the Pipil and Nicarao arrived as far south as northwestern Costa Rica.

They formed the Aztec Empire after allying with the Tepanecs and Acolhua people of Texcoco, spreading the political and linguistic influence of the Nahuas well into Central America.

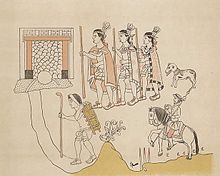

In 1519 an expedition of Spaniards sailing from Cuba under the leadership of Hernán Cortés arrived on the Mexican gulf coast near the Totonac city of Quiyahuiztlan.

It consisted mostly in the mendicants who sought to convert the population to Catholicism, and the reorganization of the indigenous tributary system to benefit individual Spaniards.

[61][62] In this early period, the hereditary indigenous ruler or tlatoani and noblemen continued to hold power locally and were key to mobilizing tribute and labor for encomenderos.

Nahua forces often formed the bulk of the Spanish military expeditions that conquered other Mesoamerican peoples, such as the Maya, Zapotecs, and Mixtecs.

Often they kept practicing their own religion in the privacy of their homes, especially in rural areas where Spanish presence was almost completely lacking and the conversion process was slow.

It was established by the Franciscans whose aim was to educate young Nahua noblemen to be Catholic priests who were trilingual: literate in Spanish, Latin and Nahuatl.

A classic study of sixteenth-century Tlaxcala, the main ally of the Spaniards in the conquest of the Mexica, shows that much of the prehispanic structure continued into the colonial period.

showing not only that literacy of some elite men in alphabetic writing in Nahuatl was a normal part of everyday life at the local level[69] and that the notion of making a final will was expected, even for those who had little property.

[70][71][72] From the mid-seventeenth century to the achievement of independence in 1821, Nahuatl shows considerable impact from the European sphere and a full range of bilingualism.

[82] Labor arrangements between Nahuas and Spaniards were largely informal, rather than organized through the mainly defunct encomienda and the poorly functioning repartimiento.

The indigenous communities continued to function as political entities, but there was greater fragmentation of units as dependent villages (sujetos) of the main settlement (cabecera) sought full, independent status themselves.

With the achievement of Mexican independence in 1821, the casta system, which divided the population into racial categories with differential rights, was eliminated and the term "Indian" (indio) was no longer used by government, although it continued to be used in daily speech.

"[85] Lack of official recognition and both economic and cultural pressures meant that most Indigenous peoples in Central Mexico became more Europeanized and many became Spanish speakers.

[85] In 19th-century Mexico, the so-called "Indian Question" exercised politicians and intellectuals, who viewed Indigenous people as backward, unassimilated to the Mexican nation, whose custom of communal rather than individual ownership of land was impediment to economic progress.

The liberal Reforma enshrined in the Constitution of 1857 mandated the breakup of corporate-owned property, therefore targeting Indigenous communities and the Roman Catholic Church, which also had significant holdings.

The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in Morelos, which still had a significant Nahua population, was sparked by peasant resistance to the expansion of sugar estates.

This was preceded in the nineteenth century by smaller Indigenous revolts against encroachment, particularly during the civil war of the Reforma, foreign intervention, and a weak state following the exit of the French in 1867.

But an important nineteenth-century figure of Nahua was Ignacio Manuel Altamirano (1834–1893), born in Tixtla, Guerrero who became a well respected liberal intellectual, man of letters, politician, and diplomat.

[91] Indigenous surnames were uncommon in post-colonial Mexico but prevalent in Tlaxcala due to certain protections granted by the Spanish government in return for Tlaxcallan support during the overthrow of the Aztecs.

[93] The Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata (1879–1919) was likely of mixed Nahua-Spanish heritage, with ancestry going back to the Nahua city of Mapaztlán, in the state of Morelos.