Names of the Celts

The names Κελτοί (Keltoí) and Celtae are used in Greek and Latin, respectively, to denote a people of the La Tène horizon in the region of the upper Rhine and Danube during the 6th to 1st centuries BC in Graeco-Roman ethnography.

There is scant record of the term "Celt" being used prior to the 17th century in connection with the inhabitants of Ireland and Great Britain during the Iron Age.

However, Parthenius writes that Celtus descended through Heracles from Bretannos, which may have been a partial (because the myth's roots are older) post–Gallic War epithet of Druids who traveled to the islands for formal study, and was the posited seat of the order's origins.

The first recorded use of the name of Celts – as Κελτοί (Keltoí) – to refer to an ethnic group was by Hecataeus of Miletus, the Greek geographer, in 517 BC when writing about a people living near Massilia (modern Marseille).

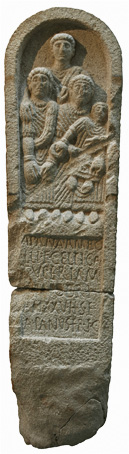

[7] According to the 1st-century poet Parthenius of Nicaea, Celtus (Κελτός, Keltos) was the son of Heracles and Celtine (Κελτίνη, Keltine), the daughter of Bretannus (Βρεττανός, Brettanos); this literary genealogy exists nowhere else and was not connected with any known cult.

Later, Ptolemy referred to the Celtici inhabiting a more reduced territory, comprising the regions from Évora to Setúbal, i.e. the coastal and southern areas occupied by the Turdetani.

Pliny mentioned a second group of Celtici living in the region of Baeturia (northwestern Andalusia); he considered that they were "of the Celtiberians from the Lusitania, because of their religion, language, and because of the names of their cities".

They comprised several populi, including the Celtici proper: the Praestamarici south of the Tambre river (Tamaris), the Supertamarici north of it, and the Nerii by the Celtic promontory (Promunturium Celticum).

Pomponius Mela affirmed that all inhabitants of Iberia's coastal regions, from the bays of southern Galicia to the Astures, were also Celtici: "All (this coast) is inhabited by the Celtici, except from the Douro river to the bays, where the Grovi dwelt (…) In the north coast first there are the Artabri, still of the Celtic people (Celticae gentis), and after them the Astures.

This is also the name of an archpriesthood of the Roman Catholic Church, a division of the archbishopric of Santiago de Compostela, encompassing part of the lands attributed to the Celtici Supertamarici by ancient authors.

An early attestation is found in Milton's Paradise Lost (1667), in reference to the Insular Celts of antiquity: [the Ionian gods ... who] o'er the Celtic [fields] roamed the utmost Isles.

[20] James Macpherson's Ossian fables, which he claimed were ancient Scottish Gaelic poems that he had "translated," added to this romantic enthusiasm.

After its use by Edward Lhuyd in 1707,[28] the use of the word "Celtic" as an umbrella term for the pre-Roman peoples of the British Isles gained considerable popularity.

Lhuyd was the first to recognise that the Irish, British, and Gaulish languages were related to one another, and the inclusion of the Insular Celts under the term "Celtic" from this time forward expresses this linguistic relationship.

The timeline of Celtic settlement in the British Isles is unclear and the object of much speculation, but it is clear that by the 1st century BC most of Great Britain and Ireland was inhabited by Celtic-speaking peoples now known as the Insular Celts.

Galatia in Anatolia) seems to be based on the same root, borrowed directly from the same hypothetical Celtic source that gave us Galli (the suffix -atai simply indicates that the word is an ethnic name).

The Proto-Indo-European verbal root in question is reconstructed by Schumacher as *gelH-,[30] meaning German: Macht bekommen über, "to acquire power over" in the Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben.

[31] The name of the Gallaeci (earlier form Callaeci or Callaici), a Celtic federation in northwest Iberia, may seem related to Galli but is not.

An earlier form was Pritani, or Πρετ(τ)αν(ν)οί in Greek (as recorded by Pytheas in the 4th century BC, among others, and surviving in Welsh as Prydain, the old name for Britain).

Related to this is *Priteni, the reconstructed self-designation of the people later called Picts, which is recorded later in Old Irish as Cruithin and Welsh as Prydyn.