Nandi people

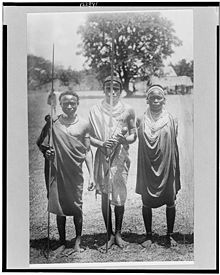

Modern ethnicities Diaspora Performing arts Government agencies Television Radio Newspapers The Nandi are part of the Kalenjin, a Nilotic tribe living in East Africa.

They traditionally have lived and still form the majority in the highland areas of the former Rift Valley Province of Kenya, in what is today Nandi County.

They include: the Nandi, Kipsigis, Tugen, Keiyo, Okiek, Marakwet, Sengwer, Sabaot, Terik, Pokot and Sebei.

Oret (clan) membership cuts across the various communities with Nandi and Kipsigis ortinwek ties being particularly intricate thus making both seem as a single identity even to date.

The traditional Nandi account is that the first settlers in their country came from Elgon during the time of the Maina[definition needed] and formed the Kipoiis clan; a name that possibly means 'the spirits'.

[6] Inward migrants and general population growth are conjectured to have led to a northward expansion of the growing identity during the eighteenth century.

These were Wareng, located to the north, Mosop in the northeast, Tindiret in the east, Soiin and Pelkut in the south, Aldai and Chesumei in the west and Emgwen in the center.

The kokwet elders were the local authority for allocating land for cultivation, they were also the body to whom the ordinary member of the tribe would look for a decision in a dispute or problem which defied solution by direct agreement between the parties.

Membership of the kokwet council was acquired by seniority and personality and within it decisions were taken by a small number of elders whose authority derived from their natural powers of leadership.

It is said they, that ibinda, the korongoro put on their ears some septook (broken pieces of calabashes) to avoid listening to the wise words of the Orkoiyot.

The earliest recorded mention of Arab caravans in Nandi oral tradition date to the 1850s during the time when the Sawe ibinda (age-set) were warriors.

Trusted Sotik and Dorobo agents were employed to act as "middle men" who would trade ivory and other coastal goods for cattle to the Nandi for a large commission.

Dutifully, a party of twenty men would be dispatched with cloth, wire, and other trade goods only to be ambushed by the Nandi and massacred."

[10] Economically, it is noted that the veterans did not receive pensions as they had expected but that they did return with their back-pay which for some amounted to as much as several hundred shillings, quite a significant sum at the time.

Much as the Government had alienated part of the Nandi Reserve the population pressure was not yet great enough to leave most men dissatisfied with the amount of land they would acquire by traditional means.

The District Commissioner was hard put in 1922 for instance to produce 200 able-bodied young men to work on a local road-building project.

[10][11] Politically, it is observed that the Nyongik assimilated back into the traditional power structure in much the same positions they had left some three or four years earlier.

The obligations and ties they resumed were to their families, age-set and korotinwek meaning the common interests of veterans gave way to a man's traditional associations.

[10] Greenstein states that in the period following the War, the minority European civilian population resident in Kenya and the Protectorate Government, were worried about the possibility of armed insurrection among the indigenous peoples.

He quotes Shiroya who was writing after the war to illustrate a then commonly held perception which was that "the ex-askari had learned and observed that without modern technology, a European was no better than an African".

[12] The introduction of the Maxim gun altered the power symmetry which Greenstein suggests was apparent to Africans hence "the deference showed, which some Europeans took as awe and respect".

Fears that appear to have been stoked by an upsurge in political activity in the 1920s, notably Archdeacon Owen's Piny Owacho (Voice of the People) movement and Harry Thuku's Young Kikuyu Association.

In 1923, the saget ab eito (sacrifice of the ox), a historically significant ceremony where leadership of the community was transferred between generations, was to take place.

This ceremony had always been followed by an increased rate of cattle raiding as the now formally recognized warrior age-set sought to prove its prowess.

The approach to a saget ab eito thus witnessed expressions of military fervour and for the ceremony all Nandi males would gather in one place.

Alarmed at the prospect and as there was also organized protest among the Kikuyu and Luo at that time, the colonial government came to believe that the Orkoiyot was planning to use the occasion of the Saget ab eito of 1923 as a cover under which to gather forces for a massive military uprising.

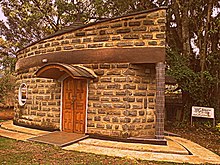

On 16 October 1923, several days before the scheduled date for the saget ab eito, the Orkoiyot Barsirian Arap Manyei and four other elders were arrested and deported to Meru.

Seroney was arrested and detained without trial for three and a half years for defending the independence of Parliament at a time when it was becoming an arm of the Executive.

He worked hard to introduce Bills that would remove or at least check the excessive powers vested in the President as a result of the numerous amendments to the Kenya Constitution.

Notable Nandi female politicians include Philomena Chelagat Mutai, a lifelong activist for the inclusion of women in Kenyan politics and society, and Sally Kosgei, a former MP for Aldai.