Napoleon's theorem

Some have suggested that it may date back to W. Rutherford's 1825 question published in The Ladies' Diary, four years after the French emperor's death,[1][2] but the result is covered in three questions set in an examination for a Gold Medal at the University of Dublin in October, 1820, whereas Napoleon died the following May.

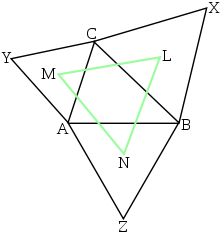

A quick way to see that △LMN is equilateral is to observe that MN becomes CZ under a clockwise rotation of 30° around A and a homothety of ratio

with the same center, and that LN also becomes CZ after a counterclockwise rotation of 30° around B and a homothety of ratio

[6][8] The theorem has frequently been attributed to Napoleon, but several papers have been written concerning this issue[9][10] which cast doubt upon this assertion (see (Grünbaum 2012)).

The following entry appeared on page 47 in the Ladies' Diary of 1825 (so in late 1824, a year or so after the compilation of Dublin examination papers).

"Since William Rutherford was a very capable mathematician, his motive for requesting a proof of a theorem that he could certainly have proved himself is unknown.

Maybe he posed the question as a challenge to his peers, or perhaps he hoped that the responses would yield a more elegant solution.

However, it is clear from reading successive issues of the Ladies' Diary in the 1820s, that the Editor aimed to include a varied set of questions each year, with some suited for the exercise of beginners.

Plainly there is no reference to Napoleon in either the question or the published responses, which appeared a year later in 1826, though the Editor evidently omitted some submissions.

Indeed, the Woodburn Problem Solving Group, as it might be known today, was sufficiently well known by then to be written up in A Historical, Geographical, and Descriptive View of the County of Northumberland ... (2nd ed.

It had been thought that the first known reference to this result as Napoleon's theorem appears in Faifofer's 17th Edition of Elementi di Geometria published in 1911,[11] although Faifofer does actually mention Napoleon in somewhat earlier editions.

But this is moot because we find Napoleon mentioned by name in this context in an encyclopaedia by 1867.

What is of greater historical interest as regards Faifofer is the problem he had been using in earlier editions: a classic problem on circumscribing the greatest equilateral triangle about a given triangle that Thomas Moss had posed in the Ladies Diary in 1754, in the solution to which by William Bevil the following year we might easily recognize the germ of Napoleon's Theorem - the two results then run together, back and forth for at least the next hundred years in the problem pages of the popular almanacs: when Honsberger proposed in Mathematical Gems in 1973 what he thought was a novelty of his own, he was actually recapitulating part of this vast, if informal, literature.

Just as authors returned repeatedly to consider other properties of Euclid's Windmill or Bride's Chair, so the equivalent figure with equilateral triangles replacing squares invited - and received - attention.

Perhaps the most majestic effort in this regard is William Mason's Prize Question in the Lady's and Gentleman's Diary for 1864, the solutions and commentary for which the following year run to some fifteen pages.

In the Geometry paper, set on the second morning of the papers for candidates for the Gold Medal in the General Examination of the University of Dublin in October 1820, the following three problems appear.

However, there are several items of cognate interest in the problem pages of the popular almanacs both going back to at least the mid-1750s (Moss) and continuing on to the mid-1860s (Mason), as alluded to above.

As it happens, Napoleon's name is mentioned in connection with this result in no less a work of reference than Chambers's Encyclopaedia as early as 1867 (Vol.

[13]But then the result had appeared, with proof, in a textbook by at least 1834 (James Thomson's Euclid, pp.

In an endnote (p. 372), Thomason adds This curious proposition I have not met with, except in the Dublin Problems, published in 1823, where it is inserted without demonstration.In the second edition (1837), Thomson extended the endnote by providing proof from a former student in Belfast: The following is an outline of a very easy and neat proof it by Mr. Adam D. Glasgow of Belfast, a former student of mine of great taste and talent for mathematical pursuits:Thus, Thomson does not appear aware of the appearance of the problem in the Ladies' Diary for 1825 or the Gentleman's Diary for 1829 (just as J. S. Mackay was to remain unaware of the latter appearance, with its citation of Dublin Problems, while noting the former; readers of the American Mathematical Monthly have a pointer to Question 1249 in the Gentleman's Diary from R. C. Archibald in the issue for January 1920, p. 41, fn.

7, although the first published solution in the Ladies Diary for 1826 shows that even Archibald was not omniscient in matters of priority).

P. G. Tait, then Professor of Natural Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh, is listed amongst the contributors, but J. U. Hillhouse, Mathematical Tutor also at the University of Edinburgh, appears amongst other literary gentlemen connected for longer or shorter times with the regular staff of the Encyclopaedia.

However, in Section 189(e) of An Elementary Treatise on Quaternions,[15] also in 1867, Tait treats the problem (in effect, echoing Davies' remarks in the Gentleman's Diary in 1831 with regard to Question 1265, but now in the setting of quaternions): If perpendiculars be erected outwards at the middle points of the sides of a triangle, each being proportional to the corresponding side, the mean point of their extremities coincides with that of the original triangle.

The discussion is retained in subsequent editions in 1873 and 1890, as well as in his further Introduction to Quaternions [16] jointly with Philip Kelland in 1873.

Analytically, it can be shown[6] that each of the three sides of the outer Napoleon triangle has a length of

The relation between the latter two equations is that the area of an equilateral triangle equals the square of the side times

[23] Given a hexagon ABCDEF with equilateral ∆'s ABG, DHC, IEF constructed on the alternate sides AB, CD and EF, either inwardly or outwardly.

[24] (If, for example, we let points A and F coincide, as well as B and C, and D and E, then Dao Than Oai’s result reduces to Napoleon’s theorem).