Napoléon (1927 film)

[8] In the winter of 1783, young Napoleon Buonaparte (Vladimir Roudenko) is enrolled at Brienne College, a military school for sons of nobility, run by the religious Minim Fathers in Brienne-le-Château, France.

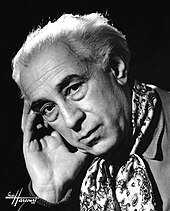

The leaders of the group, Georges Danton (Alexandre Koubitzky), Jean-Paul Marat (Antonin Artaud) and Maximilien Robespierre (Edmond Van Daële), are seen conferring.

[9] A young army captain, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle (Harry Krimer) has written the words and brought the song to the club.

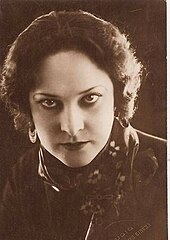

Splashed with water in a narrow Paris street, Napoleon is noticed by Joséphine de Beauharnais (Gina Manès) and Paul Barras (Max Maxudian) as they step from a carriage on their way into the house of Mademoiselle Lenormand (Carrie Carvalho), the fortune teller.

The shepherd Santo-Ricci (Henri Baudin) interrupts the happy welcome to tell Napoleon the bad news that Corsica's president, Pasquale Paoli (Maurice Schutz), is planning to give the island to the British.

Riding a horse and revisiting places of his childhood, Napoleon stops in Milelli gardens and considers whether to retreat and protect his family, or to advance into the political arena.

Later in the streets of Ajaccio, Pozzo di Borgo (Acho Chakatouny) encourages a mob to put Napoleon to death for opposing Paoli, and the townsfolk surround the Buonaparte home.

The larger ship is steered to rescue the unknown boat, and as it is pulled close, Napoleon is recognised, lying unconscious at the bottom, gripping the French flag.

The British warship HMS Agamemnon sights Le Hasard, and a young officer, Horatio Nelson (Olaf Fjord), asks his captain if he might be allowed to shoot at the enemy vessel and sink it.

Two months later, General Jean François Carteaux (Léon Courtois), in control of a French army, is ineffectively besieging the port of Toulon, held by 20,000 English, Spanish and Italian troops.

In an archive room filled with the files of condemned prisoners, clerks Bonnet (Boris Fastovich-Kovanko [fr]) and La Bussière (Jean d'Yd) work secretly with Fleuri to destroy (by eating) some of the dossiers including those for Napoleon and Joséphine.

The plans are sent back, and Napoleon pastes them up to cover a broken window in the poor apartment he shares with Captain Marmont (Pierre de Canolle), Sergeant Junot (Jean Henry) and the actor Talma (Roger Blum).

[13][14] Beginning in late 1979, Carmine Coppola composed a score incorporating themes taken from various sources such as Ludwig van Beethoven, Hector Berlioz, Bedřich Smetana, Felix Mendelssohn and George Frideric Handel.

Coppola's score was heard first in New York at Radio City Music Hall performed for very nearly four hours, accompanying a film projected at 24 frames per second as suggested by producer Robert A.

Filming the whole story in Polyvision was logistically difficult as Gance wished for a number of innovative shots, each requiring greater flexibility than was allowed by three interlocked cameras.

When the film was greatly trimmed by the distributors early on during exhibition, the new version only retained the centre strip to allow projection in standard single-projector cinemas.

[23][24][25] Brownlow's 1980 reconstruction was re-edited and released in the United States by American Zoetrope (through Universal Pictures) with a score by Carmine Coppola performed live at the screenings.

The acclaim surrounding the film's revival brought Gance much-belated recognition as a master director before his death eleven months later, in November 1981.

When it was screened at the Barbican Centre in London, French actress Annabella, who plays the fictional character Violine in the film (personifying France in her plight, beset by enemies from within and without), was in attendance.

She was introduced to the audience prior to screenings and during one of the intervals sat alongside Kevin Brownlow, signing copies of the latter's book about the history and restoration of the film.

One such screening was at the Royal Festival Hall in London in December 2004, including a live orchestral score of classical music extracts arranged and conducted by Carl Davis.

[27] Coppola's single-screen version of the film was last projected for the public at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in two showings in celebration of Bastille Day on 13–14 July 2007, using a 70 mm print struck by Universal Studios in the early 1980s.

[28] At the San Francisco Silent Film Festival in July 2011, Brownlow announced there would be four screenings of his 2000 version, shown at the original 20 frames per second, with the final triptych and a live orchestra, to be held at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, from 24 March to 1 April 2012.

[2][29][30][31][32] At a screening of Napoléon on 30 November 2013, at the Royal Festival Hall in London, full to capacity, the film and orchestra received a standing ovation, without pause, from the front of the stalls to the rear of the balcony.

The BBC website announced: "Historian Kevin Brownlow tells Francine Stock about his 50-year quest to restore Abel Gance's silent masterpiece Napoleon to its five and half-hour glory, and why the search for missing scenes still continues even though the film is about to be released on DVD for the very first time.

The website's critics consensus reads: "Monumental in scale and distinguished by innovative technique, Napoléon is an expressive epic that maintains a singular intimacy with its subject.

"[40] Anita Brookner of London Review of Books wrote that the film has an "energy, extravagance, ambition, orgiastic pleasure, high drama and the desire for endless victory: not only Napoleon’s destiny but everyone’s most central hope.

"[42] Judith Martin of The Washington Post wrote that the film "inspires that wonderfully satisfying theatrical experience of whole-heartedly cheering a hero and hissing villains, while also providing the uplift that comes from a real work of art" and praised its visual metaphors, editing, and tableaus.

"[6] Mark Kermode described the film "as significant to the evolution of cinema as the works of Sergei Eisenstein and D. W. Griffith" that "created a kaleidoscopic motion picture which stretched the boundaries of the screen in every way possible.

Technically [Gance] was ahead of his time and he introduced new film techniques – in fact Eisenstein credited him with stimulating his initial interest in montage – but as far as story and performance goes it's a very crude picture.