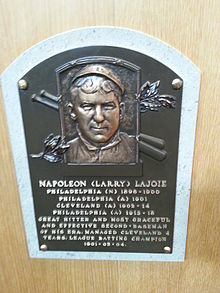

Nap Lajoie

He'd take your leg off with a line drive, turn the third baseman around like a swinging door and powder the hand of the left fielder.

[11]: p.179 When word of Lajoie's baseball ability spread, he began to play for other semi-professional teams at $2 to $5 per game ($73 to $183 in current dollar terms).

[7] He left Woonsocket and his $7.50 per week ($275 in current dollar terms) working as a taxi driver and joined the Class B New England League's Fall River Indians in 1896.

[12]: p.19 The Philadelphia Phillies of the MLB's National League (NL) purchased Lajoie and teammate Phil Geier from Fall River for $1,500 ($54,936 in current dollar terms) on August 9.

Phillies' manager Billy Nash originally went to Fall River intending to sign Geier only but obtained Lajoie when the team agreed to include him in their asking price.

[14][15]: p.55 Author David Jordan wrote: A legend later grew up that Geier was the main target of Nash's pursuit and that Marston "threw in" Lajoie in order to get the Phillies to pay the $1,500 asking price.

While Geier was considered a good prospect, Lajoie was banging the ball at a .429 clip in his first professional season, was a fine fielder, and had already been sought by several big league clubs.

[10] Lajoie's batting average that year was .426 (due to a transcription error that was not discovered until 1954, which inaccurately gave his hit total as 220 instead of 229, it was originally recorded at .405, later changed to .422, before finally being revised again to .426).

[29] Mack responded by trading Lajoie and Bill Bernhard to the then-moribund Cleveland Bronchos, whose owner, Charles Somers, had provided considerable financial assistance to the A's in the early years.

[33] Lajoie, nicknamed "The Frenchman" and considered baseball's most famous player at the time, arrived in Cleveland on June 4; his play was immediately met with approval from fans.

[5]: p.12 [10] The Bronchos' record at the time Lajoie and fellow Athletics teammate, Bill Bernhard, joined was 11–24 and improved to 12–24 after the team's inaugural game with their new players, a 4–3 win over the Boston Americans.

[32]: p.36 The issue was finally resolved when the leagues made peace through the National Agreement in September 1903 (which also brought the formation of the World Series).

[5]: p.13 [9]: p.40 To begin the 1903 season, the club changed its name from the Bronchos to the Naps in honor of Lajoie after a readers' poll result was released by the Cleveland Press.

[40]: p.65 Franklin Lewis, sports writer and author, wrote "Lajoie, in spite of his marvelous fielding and tremendous batting, was not exactly a darling of the grandstand as a manager.

Lajoie later described the decision to take on the added duties as a player-manager as the biggest mistake of his career as he felt it negatively affected his play.

In his final major league game, he hit a triple to help Athletics pitcher Joe Bush win his no-hitter.

[22]: p.100 He later was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers for $3,000 ($60,770 in current dollar terms) in March 1918 but the contract was annulled by the Commissioner's office and made a free agent to which Lajoie was "well pleased".

He helped lead the team to a third-place finish but the season was impacted due to the U.S.'s involvement in World War I. Lajoie made his services available to the draft board but they rejected his offer.

Baseball historian David Anderson wrote: Nap Lajoie reached the milestone later in the summer with even less hoopla, in an age when individual records received little attention from the press and were generally scorned by many players.

The modesty of Wagner and Lajoie over their achievements contrasted sharply with Cobb's ambition and overriding interest in his individual numbers.

[65] Lajoie and the Naps faced a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns in Sportsman's Park, Cleveland's final two games of the season.

After a sun-hindered fly ball went for a stand-up triple and another batted ball landed for a cleanly hit single, Lajoie had five subsequent hits – bunt singles dropped in front of rookie third baseman Red Corriden (whose normal position was shortstop), who was playing closer to shallow left field on orders, it has been suggested, of manager Jack O'Connor.

Although the AL office had not officially announced the results, Lajoie began to receive congratulations from fans and players, including eight of Cobb's Detroit Tigers teammates.

"[64] Howell was reported to have offered a bribe to Parish, which as described in Al Stump's biography of Cobb, was a $40 ($1,263 in current dollar terms) suit.

"[32]: p.125 Lajoie said, "I am quite satisfied that I was treated fairly in every way by President Johnson, but I think the scorer at St. Louis made an error in not crediting me with nine hits.

"[32]: p.125 The Sporting News published an article written by Paul MacFarlane in its April 18, 1981, issue where historian Pete Palmer had discovered that while Cobb's September 24 doubleheader was not correctly tabulated (perhaps purposely) according to the correct date, the second game's statistics were in fact included in the next day's ledger, thus incorrectly recording a second 2-for-3 performance from Cobb which meant Lajoie's average was greater.

Total Baseball, which is now the official major-league record, lists both men at .384 in its seasonal section, but its player register has Lajoie at the same number and Cobb at .383—so even the various editors of that source do not, or cannot, agree.

[41]: p.339 Baseball historian William McNeil rates Lajoie as the game's greatest second baseman, when combining both offensive and defensive impact.

[81] Lajoie is mentioned in the poem "Line-Up for Yesterday" by Ogden Nash: L is for LajoieWhom Clevelanders love,Napoleon himself,With glue in his glove.

Big Nap Lay'-ooh-wayLajoie's likeness made a brief cameo appearance in the 1992 The Simpsons episode "Homer at the Bat" as one of the would-be ringers for Mr. Burns' company softball team.