Nathan Bedford Forrest

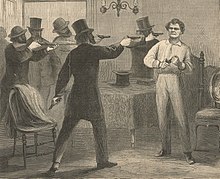

[3][4] His role in the massacre of several hundred U.S. Army soldiers at Fort Pillow remains controversial, as the most infamous application of the Confederate no-quarter policy toward black enemy combatants.

In 1869, Forrest expressed disillusionment with the terrorist group's lack of discipline,[8] and issued a letter ordering the dissolution of the Ku Klux Klan as well as the destruction of its costumes; he then withdrew from the organization.

While scholars generally acknowledge Forrest's skills and acumen as a cavalry leader and tactician, due to his pre-war slave trading and his post-war leadership of the Klan, he is now considered a shameful signifier of a bleaker, less-equal United States.

[38] After the war, a woman named Nellie Harbold placed a family reunification ad hoping to find her children, Lydia, Miley A., and Samuel Tirley, all of whom had been sold to separate buyers out of "the yard of Forrest the Trader" in Memphis in 1854.

The Memphis Avalanche suggests that as Fred is ample able to make the outlay he should either purchase his own flesh and blood from servitude, or cease his shrieks over an institution which possesses such untold horrors.In 1859, a federal investigation found that Forrest also sold 37 individuals illegally imported to the United States from Africa on the slave ship Wanderer.

[64] Forrest won praise for his performance under fire during an early victory in the Battle of Sacramento in Kentucky, the first in which he commanded troops in the field, where he routed a U.S. Army force by personally leading a cavalry charge that Brigadier General Charles Clark later commended.

After his cavalry captured a U.S. artillery battery, he broke out of a siege headed by Major General Ulysses S. Grant, rallying nearly 4,000 troops and leading them to escape across the Cumberland River.

He described the battle graphically, recounted exaggerated Union casualty figures, and noted, 'It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with the Southerners.

On May 9, 1865, at Gainesville, Forrest read his farewell address to the men under his command, urging them to "submit to the powers to be, and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land.

Nearly ruined as the result of this failure, Forrest spent his final days running an eight-hundred-acre farm on land he leased on President's Island in the Mississippi River, where he and his wife lived in a log cabin.

As the Klan's first national leader, he became the Lost Cause of the Confederacy's avenging angel, galvanizing a loose collection of boyish secret social clubs into a reactionary instrument of terror still feared today.

[173] Author Andrew Ward, however, writes, "In the spring of 1867, Forrest and his dragoons launched a campaign of midnight parades; 'ghost' masquerades; and 'whipping' and even 'killing Negro voters and white Republicans, to scare blacks off voting and running for office'".

[178][179] After only a year as Grand Wizard, in January 1869, faced with an ungovernable membership employing methods that seemed increasingly counterproductive, Forrest dissolved the Klan, ordered their costumes destroyed,[180] and withdrew from participation.

[181] In 1871, the U.S. Congressional Committee Report stated that "The natural tendency of all such organizations is to violence and crime, hence it was that Gen. Forrest and other men of influence by the exercise of their moral power, induced them to disband".

Prominent ex-Confederates, including Forrest, the Grand Wizard of the Klan, and South Carolina's Wade Hampton, attended as delegates at the 1868 Democratic Convention, held at Tammany Hall headquarters at 141 East 14th Street in New York City.

Many in the United States, including President Grant, backed the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave voting rights to American men regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude".

He denied membership, but his role in the KKK was beyond the scope of the investigating committee, which wrote: "Our design is not to connect General Forrest with this order (the reader may form his own conclusion upon this question)".

[189] The committee also noted, "The natural tendency of all such organizations is to violence and crime; hence it was that General Forrest and other men of influence in the state, by the exercise of their moral power, induced them to disband".

"[191] After the lynch mob murder of four black people who had been arrested for defending themselves in a brawl at a barbecue, Forrest wrote to Tennessee governor John C. Brown in August 1874 volunteering to personally lead a posse to punish the "white marauders" responsible.

He made what The New York Times described as a "friendly speech"[193][194] during which, when offered a bouquet by the daughter of a Pole Bearers’ officer, he accepted them,[195] thanked the young black woman and kissed her on the cheek.

[10] In response to the Pole-Bearers speech, the Cavalry Survivors Association of Augusta, the first Confederate organization formed after the war, held a meeting on July 30, 1875 in which Captain Francis Edgeworth Eve, a former enlisted cavalry soldier who had been elected to his rank in the Georgia Hussars, gave a speech expressing strong disapproval of Forrest's remarks promoting inter-ethnic harmony, ridiculing his faculties and judgment and berating the woman who gave Forrest flowers as "a mulatto wench".

The school unveiled its latest mascot, a winged horse named "Lightning" inspired by the mythological Pegasus, during halftime of a basketball game against rival Tennessee State University on January 17, 1998.

[226] The city council then voted on December 20, 2017, to sell Health Sciences Park to Memphis Greenspace, a new non-profit corporation not subject to the Heritage Protection Act, which removed the statue and another of Jefferson Davis that same evening.

The effort was spearheaded by Shelby County Commissioner Tami Sawyer, an educator and Memphis native who founded a group called Take 'Em Down 901 to advocate for the removal of Confederate iconography.

[249] U.S. Army General William Tecumseh Sherman called him "that devil Forrest" in wartime communications with Ulysses S. Grant and considered him "the most remarkable man our civil war produced on either side".

Paramount in his strategy was fast movement, even if it meant pushing his horses at a killing pace, to constantly harass the enemy during raids by disrupting their supply trains and communications with the destruction of railroad tracks and the cutting of telegraph lines, as he wheeled around his opponent's flank.

Now often recast as "Getting there firstest with the mostest",[255] this misquote first appeared in a New York Tribune article written to provide colorful comments in reaction to European interest in Civil War generals.

But those virtues, he continues, are useful to armies when they are demonstrated by junior officers and enlisted men, not generals who must consider the larger picture, as Forrest failed to do when he led troops to Ebenezer Church rather than prepare a more robust defense at Selma, a loss that effectively ended the war as the Union destroyed the Confederacy's last manufacturing center.

His failures at Chickamauga left Bragg with a more ephemeral victory than he might have otherwise gained, at Tupelo he escaped but at the cost of his ability to mount serious raids on Sherman's supply lines, and Johnsonville, despite its overwhelming success, hurt the Confederacy as it led Hood to delay his advance into Tennessee, allowing Thomas to consolidate his defenses for the Battle of Nashville, where Union victory ended the Army of Tennessee as a force to reckon with, and with it the Confederacy's Western Theater campaign.

Richard L. Fuchs, author of An Unerring Fire, concluded: The affair at Fort Pillow was simply an orgy of death, a mass lynching to satisfy the basest of conduct—intentional murder—for the vilest of reasons—racism and personal enmity.