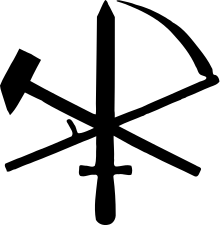

National Bolshevism

[6][7][need quotation to verify] During the 1920s, a number of German intellectuals began a dialogue which created a synthesis between radical nationalism (typically referencing Prussianism) and Bolshevism as it existed in the Soviet Union.

[10] Co-publisher and illustrator of Widerstand was the openly antisemitic A. Paul Weber, who saw himself primarily concerned with the future of Germany due to the growing popularity of Nazism.

[12] The ideology of Ernst Niekisch and the group which had formed around the publication, named Widerstandskreis, has been described as anti-democratic, nationalist, anti-capitalist, anti-western, as well as exhibiting racist and fascist traits.

While initially somewhat receptive to Nazism, Paetel quickly grew disillusioned with the NSDAP as he no longer believed they were genuinely committed to either revolutionary activity or socialist economics.

Similarly to the Communists and Strasserists, Paetel too, tried to split off vulnerable elements of the Nazi Party; an example of this being his largely unsuccessful attempt to win over a section of the Hitler Youth to his cause.

[25][24] Similarly to the National Bolshevism of Niekisch, Paetel's ideology was strongly anti-western, focusing on anti-imperialism and opposition to the Treaty of Versailles, as well as being characterized by an Anti-French sentiment.

[24] The National Bolshevik project of figures such as Niekisch and Paetel was typically presented as just another strand of Bolshevism by the Nazi Party, and was thus viewed just as negatively and as part of a "Jewish conspiracy".

Despite opposition to National Bolshevism, usually on the grounds that it tends to take Marxist influence, a similarly syncretic, but non-Marxist, tendency had developed in the left-wing of the Nazi Party.

As the Russian Civil War dragged on, a number of prominent Whites switched to the Bolshevik side because they saw it as the only hope for restoring greatness to Russia.

His followers, the Smenovekhovtsy (named after a series of articles he published in 1921) Smena vekh (Russian: change of milestones), came to regard themselves as National Bolsheviks, borrowing the term from Niekisch.

[30] Ustryalov and others sympathetic to the Smenovekhovtsy cause, such as Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy and Ilya Ehrenburg, were eventually able to return to the Soviet Union and following the co-option of aspects of nationalism by Stalin and his ideologue Andrei Zhdanov enjoyed membership of the intellectual elite under the designation non-party Bolsheviks.

[34][35] Many of the original proponents of National Bolshevism, such as Ustryalov and members of the Smenovekhovtsy were suppressed and executed during the Great Purge for "anti-Soviet agitation", espionage and other counter-revolutionary activities.

[36][37] Russian historian Andrei Savin stated that Stalin's policy shifted away from internationalism towards National Bolshevism[38] a view also shared by David Brandenberger[39] and Evgeny Dobrenko.

[52] Solzhenitsyn and his followers, known as vozrozhdentsy (revivalists), differed from the National Bolsheviks, who were not religious in tone (although not completely hostile to religion) and who felt that involvement overseas was important for the prestige and power of Russia.

[65] According to Gylling, the successful construction of socialism in Karelia required " the implementation of nationalist politics in a communist spirit", which would win the support of the anti-Russian peasant population.

[70] During Gylling's time, Finnish workers from Canada and the United States were also systematically enticed to Soviet Karelia, from which several thousands would be recruited during the Great Depression.

[72] Yrjö Ruutu, the founder and leader of the interwar Strasserist National Socialist Union of Finland, joined the communist Finnish People's Democratic League after the Second World War.

[73] After the war, the leader of the Nazi Finnish-Socialist Workers' Party Ensio Uoti praised Stalin's "nationalist communism" and applauded him taking a stand against "jewish internationalism and jew-finance capitalism".

[80] The Franco-Belgian Parti Communautaire National-Européen shares National Bolshevism's desire for the creation of a united Europe as well as many of the NBP's economic ideas.

[81] The Nouvelle Droite tendency was influenced by both left-wing and right-wing doctrines, taking heavy inspiration from Antonio Gramsci,[82] with many supporters of the concept calling themselves "Gramscians of the Right".

[85] In 1944, Indian nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose called for "a synthesis between National Socialism and communism" to take root in India.

After the death of Avraham Stern, the new leadership of the Israeli paramilitary organization Lehi moved towards support for Joseph Stalin[87] and the doctrine of National Bolshevism,[88][89] which was a break from the group's fascist outlook under its previous leader.