Italianization

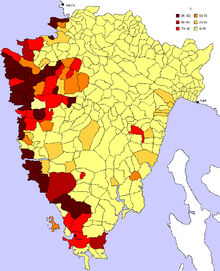

Between 1922 and the beginning of World War II, the affected people were the German-speaking and Ladin-speaking populations of Trentino-Alto Adige, Friulians, and Slovenes and Croats in the Julian March.

The program was later extended to areas annexed during World War II, affecting Slovenes in the Province of Ljubljana, and Croats in Gorski Kotar and coastal Dalmatia, Greeks in the Ionian islands and, to a lesser extent, to the French- and Arpitan-speaking regions of the western Alps (such as the Aosta valley).

On the other hand, other indigenous communities, such as in Lombardy, Venetia and the island of Sardinia, had already undergone cultural and linguistic Italianization starting from an earlier period.

The period of violent persecution of Slovenes in Trieste began with riots on 13 April 1920, which were organised as a retaliation for the assault on the Italian occupying troops by the local Croatian population in the 11 July Split incident.

Many Slovene-owned shops and buildings were destroyed during the riots, which culminated in the burning down of the Narodni dom ("National Home"), the community hall of the Triestine Slovenes, by a group of Italian Fascists, led by Francesco Giunta.

Slovene and Croat societies and sporting and cultural associations had to cease every activity in line with a decision of provincial Fascist secretaries dated 12 June 1927.

[7] Among the notable Slovene émigrés from Trieste were the writers Vladimir Bartol and Josip Ribičič, the legal theorist Boris Furlan, and the architect Viktor Sulčič.

During the Italian annexation of Dalmatia in World War II, Giuseppe Bastianini immediately gave way to a massive and violent Italianization of the annexed provinces: the political secretaries of the fascist party, of the after-work club, of the agricultural consortia and doctors, teachers, municipal employees, midwives were sent to administer them, immediately hated by those whose jobs they took away.

Several factors limited the effects of the Italian policy, namely the adverse nature of the territory (mainly mountains and valleys of difficult access), the difficulty for the Italian-speaking individuals to adapt to a completely different environment and, later on, the alliance between Germany and Italy: under the 1939 South Tyrol Option Agreement, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini determined the status of the German people living in the province.

Following World War II, South Tyrol was one of the first regions to be granted autonomy on the ground of its peculiar linguistic situation; any further attempts at Italianization were formally abandoned.

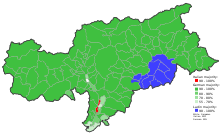

In 1720, the island of Sardinia was ceded to Alpine House of Savoy, which at the time already controlled a number of other states in the Italian mainland, most notably Piedmont.

In fact, the complex linguistic composition of the native islanders, theretofore extraneous to Italian and its cultural sphere, had been previously roofed by Spanish as the prestige language of the upper class for centuries; in this context, Italianization, while difficult at first, was intended as a cultural policy whereby the social and economic structures of the island could become increasingly intertwined with the Mainland and expressly Piedmont, where the Kingdom's central power lay.

[25] The 1847 Perfect Fusion, performed with an assimilationist intent[26] and politically analogous to the Acts of Union between Britain and Ireland, determined the conventional moment wherefrom, according to Antonietta Dettori, the Sardinian language ceased to be regarded as an identity marker of a specific ethnic group, and was instead lumped in with a dialectal conglomerate which, in the Mainland, had long been subordinate to the national language.

[32] After the end of the Second World War, efforts continued to be made to further Italianize the population, with the justification that by doing so, as the principles of the modernization theory ran, the island could rid itself of the "ancient traditional practices" which held it back, regarded as a legacy of barbarism to be disposed of at once in order to join the Mainland's economic growth;[33] Italianization had thus become a mass phenomenon, taking roots in the hitherto predominantly Sardinian-speaking villages.

[38] Research on ethnolinguistic prejudice has pointed to feelings of inferiority amongst the Sardinians in relation with mainlanders and the Italian language, perceived as a symbol of continental superiority and cultural dominance.

[46] A 2012 study conducted by the University of Cagliari and Edinburgh found that the interviewees from Sardinia with the strongest sense of Italian identity were also those expressing the most unfavourable opinion towards Sardinian.

Mussolini informed General Carlo Geloso that the Ionian Islands would form a separate Italian province through a de facto annexation, but the Germans would not approve it.

Finally, on 22 April 1941, after discussions between the German and Italian rulers, Hitler agreed that Italy could proceed with a de facto annexation of the islands.

As soon as the fascist governor Piero Parini had installed himself on Corfu he vigorously began a forced Italianization policy that lasted until the end of the war.

Italian was designated the islands' only official language; a new currency, the Ionian drachma, was introduced with the aim to hamper trade with the rest of Greece, which was forbidden by Parini.