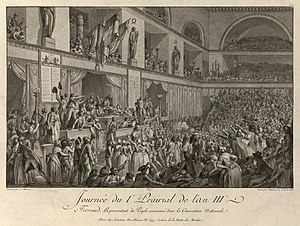

National Convention

The eight months from the fall of 1793 to the spring of 1794, when Maximilien Robespierre and his allies dominated the Committee of Public Safety, represent the most radical and bloodiest phase of the French Revolution, known as the Reign of Terror.

The low turn-out was partly due to a fear of victimization; in Paris, Robespierre presided over the elections and, in concert with the radical press, managed to exclude any candidate of royalist sympathies.

[14] The Montagnards drew their support from the Paris Commune and the popular societies such as the Jacobin Club and the Cordeliers, they got their name from the high bleachers on which they sat while the Convention was in session.

Much of the Gironde wished to remove the Assembly from a city dominated by "agitators and flatterers of the people" but did not yet encourage an aggressive federalism, which would have run counter to its political ambitions.

Most Montagnards favoured judgment and execution, but the Girondins were divided concerning Louis's fate, with some arguing for royal inviolability, others supporting clemency and still others advocating lesser punishment or banishment.

The Girondins had relied on votes from the majority of the deputies, many of whom were alarmed as well as scandalized by the September massacres, but their insistence on monopolising all positions of authority during the Convention, and their attacks on the Montagnard leaders, soon irritated them and caused them to regard the party as a faction.

Since the king's trial, the sans-culottes had been constantly assailing the "appealers" (appelants), quickly came to desire their expulsion from the Convention and demanded the establishing a Revolutionary Tribunal to deal with supposed aristocratic plots.

[25] Military setbacks from the First Coalition, Charles François Dumouriez's defection to the enemy and the War in the Vendée, which began in March 1793, were all used as arguments by Montagnards and sans-culottes to portray Girondins as soft.

In reply, Maximin Isnard, who was presiding over the Convention, launched into a diatribe reminiscent of the Brunswick Manifesto: "If any attack made on the persons of the representatives of the nation, then I declare to you in the name of the whole country that Paris would be destroyed".

[29] The Montagnards attempted to reassure the middle classes by rejecting any idea of terror, by protecting property rights and by restricting the popular movement to very narrowly-circumscribed limits.

[41] The dictatorship of the Convention and the committees, simultaneously supported and controlled by the Parisian sections, representing the sovereign people in permanent session, lasted from June to September.

[43] The committee was always managed collegially, despite the specific nature of the tasks of each director: the division into "politicians" and "technicians" was a Thermidorian invention, intended to lay the corpses of the Terror at the door of the Robespierrists alone.

Robert Lindet had qualms about the Terror which, by contrast, was the outstanding theme of Collot d'Herbois and Billaud-Varenne, latecomers to the committee, forced on it by the sans-culottes in September; unlike Robespierre and his friends, Lazare Carnot had given his support only provisionally and for reasons of state to a policy concession to the people.

[38] The Committee had to set itself above all, and choose those popular demands which were most suitable for achieving the Assembly's aims: to crush the enemies of the Republic and dash the last hopes of the aristocracy.

[44] The ensemble of institutions, measures and procedures which constituted it was codified in a decree of 14 Frimaire (4 December) which set the seal on what had been the gradual development of centralized dictatorship founded on the Terror.

Raw materials were carefully sought out: metal of all kinds, church bells, old paper, rags and parchments, grasses, brushwood, and even household ashes for manufacturing of potassium salts, and chestnuts for distilling.

All businesses were placed at the disposal of the nation: forests, mines, quarries, furnaces, forges, tanneries, paper mills, large cloth factories and shoe making workshops.

[49] Still Paris became calmer because the sans-culottes were gradually finding ways to subsist; the levée en masse and the formation of the revolutionary army were thinning their ranks; many now were working in arms and equipment shops or in the offices of the committees and ministries, which were expanded enormously.

François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers, Lazare Hoche, Jean Baptiste Kléber, André Masséna, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, and a host of others, backed by officers who combined abilities as soldiers and their political sense.

Firstly, those who were later called Hébertists although Jacques Hébert himself was never the official leader of a party that advocated war to the death and adopted the program of the enragés, ostensibly because the sans-culottes approved it.

In order to balance the contradictory demands of these two factions, the Revolutionary Government attempted to maintain a position halfway between the moderate Dantonists (citras) and the extremist Hébertists (ultras).

The Committee linked Hébert, Charles-Philippe Ronsin, François-Nicolas Vincent, and Antoine-François Momoro to the émigrés Proli, Anacharsis Cloots and Pereira, so as to present the Hébertists as parties to the "foreign plot".

The Revolutionary Army was disbanded, the inspectors of food-hoarding were dismissed, Jean Baptiste Noël Bouchotte lost the War Office, the Cordeliers Club was forced to self-censor and the Government pressure brought about closing 39 popular societies.

[77] When pressured by the Society of the Friends of the Blacks to end the slave trade in the colonies, the National Convention refused on the grounds of slavery being too core to the French economic wealth.

On hearing the news the Paris Commune, loyal to the man who had inspired it, called for an insurrection and released the arrested deputies in the evening and mobilized two or three thousand militants.

[98] On the morning of 12 Germinal (1 April) crowds gathered on the Ile de la Cité and, pushing aside the palace guards, burst into the chamber where the Convention met.

"[1] By a decree of 4 February 1794 (16 Pluviôse) it also ratified and expanded to the whole French colonial empire the 1793 abolition of slavery on Saint-Domingue by civil commissioners Sonthonax and Polverel, though this did not affect Martinique or Guadeloupe and was abolished by the law of 20 May 1802.

[107] Under a public assistance law of 19 March 1793, various principles were established such as state aid to be distributed according to population in each department, while work was to be provided to the able-bodied and home relief "wherever possible for other varieties of the needy," while almsgiving was prohibited.

A later public assistance law dated 28 June 1793 provided for state aid to be given through district ‘agencies’ to the aged, children and, for the first time in the history of France, unmarried mothers.

A variety of local and concrete welfare projects were pursued by the Jacobins, including a program that provided for free healthcare for armaments workers, along with pay for sick leave and disability and death benefits.

Jacques-Louis David , 1793, Brussels