Nature versus nurture

The view that humans acquire all or almost all their behavioral traits from "nurture" was termed tabula rasa ('blank tablet, slate') by John Locke in 1690.

As both "nature" and "nurture" factors were found to contribute substantially, often in an inextricable manner, such views were seen as naive or outdated by most scholars of human development by the 21st century.

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, complained that by denying the possibility of any innate ideas, Locke "threw all order and virtue out of the world," leading to total moral relativism.

[20] In the early 20th century, there was an increased interest in the role of one's environment, as a reaction to the strong focus on pure heredity in the wake of the triumphal success of Darwin's theory of evolution.

[21] During this time, the social sciences developed as the project of studying the influence of culture in clean isolation from questions related to "biology.

This is based on the following quote which is frequently repeated without context, as the last sentence is frequently omitted, leading to confusion about Watson's position:[22]Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select – doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.

I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years.During the 1940s to 1960s, Ashley Montagu was a notable proponent of this purist form of behaviorism which allowed no contribution from heredity whatsoever:[23] Man is man because he has no instincts, because everything he is and has become he has learned, acquired, from his culture ... with the exception of the instinctoid reactions in infants to sudden withdrawals of support and to sudden loud noises, the human being is entirely instinctless.

Organised opposition to Montagu's kind of purist "blank-slatism" began to pick up in the 1970s, notably led by E. O. Wilson (On Human Nature, 1979).

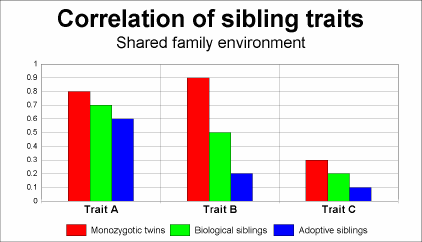

The tool of twin studies was developed as a research design intended to exclude all confounders based on inherited behavioral traits.

"[26] In a comparable avenue of research, anthropologist Donald Brown in the 1980s surveyed hundreds of anthropological studies from around the world and collected a set of cultural universals.

"[30] The situation as it presented itself by the end of the 20th century was summarized in The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2002) by Steven Pinker.

The book became a best-seller, and was instrumental in bringing to the attention of a wider public the paradigm shift away from the behaviourist purism of the 1940s to 1970s that had taken place over the preceding decades.

Pinker focuses on reasons he assumes were responsible for unduly repressing evidence to the contrary, notably the fear of (imagined or projected) political or ideological consequences.

[33] For an individual, even strongly genetically influenced, or "obligate" traits, such as eye color, assume the inputs of a typical environment during ontogenetic development (e.g., certain ranges of temperatures, oxygen levels, etc.).

This problem can be overcome by finding existing populations of humans that reflect the experimental setting the researcher wishes to create.

A classic example of gene–environment interaction is the ability of a diet low in the amino acid phenylalanine to partially suppress the genetic disease phenylketonuria.

Individual development, even of highly heritable traits, such as eye color, depends on a range of environmental factors, from the other genes in the organism, to physical variables such as temperature, oxygen levels etc.

[40] With virtually all biological and psychological traits, however, genes and environment work in concert, communicating back and forth to create the individual.

[41] Extreme genetic or environmental conditions can predominate in rare circumstances—if a child is born mute due to a genetic mutation, it will not learn to speak any language regardless of the environment; similarly, someone who is practically certain to eventually develop Huntington's disease according to their genotype may die in an unrelated accident (an environmental event) long before the disease will manifest itself.

Steven Pinker likewise described several examples:[42][43][C]oncrete behavioral traits that patently depend on content provided by the home or culture—which language one speaks, which religion one practices, which political party one supports—are not heritable at all.

It would be more accurate to state that the degree of heritability and environmentality is measured in its reference to a particular phenotype in a chosen group of a population in a given period of time.

For example, the rewarding sweet taste of sugar and the pain of bodily injury are obligate psychological adaptations—typical environmental variability during development does not much affect their operation.

Subsequent developmental genetic analyses found that variance attributable to additive environmental effects is less apparent in older individuals, with estimated heritability of IQ increasing in adulthood.

[59] Evidence from behavioral genetic research suggests that family environmental factors may have an effect upon childhood IQ, accounting for up to a quarter of the variance.

The American Psychological Association's report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" (1995) states that there is no doubt that normal child development requires a certain minimum level of responsible care.

For example, research has shown that factors such as access to education, nutrition, and social support can have a significant impact on IQ.

Furthermore, research has suggested that certain experiences during early childhood, such as exposure to lead or other environmental toxins, can have a negative impact on IQ.

A supporting article had focused on the heritability of personality (which is estimated to be around 50% for subjective well-being) in which a study was conducted using a representative sample of 973 twin pairs to test the heritable differences in subjective well-being which were found to be fully accounted for by the genetic model of the Five-Factor Model's personality domains.

An example of a visible human trait for which the precise genetic basis of differences are relatively well known is eye color.

The growing consensus in medicine is that ... children should be assigned to their chromosomal (i.e., genetic) sex regardless of anatomical variations and differences—with the option of switching, if desired, later in life.