Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945)

Following the Anschluss of Austria in March 1938 and the Munich Agreement in September of that same year, Adolf Hitler annexed the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia on 1 October, giving Germany control of the extensive Czechoslovak border fortifications in this area.

Germany had the second-largest economy in the world, [citation needed] but German agriculture was not capable of feeding the population, and there was also a lack of many raw materials, which had to be imported.

[4] Though the Four Year Plan aimed at autarky, there were certain raw materials such as high-grade iron, oil, chrome, nickel, tungsten, and bauxite that Germany did not have and had to be imported.

[7] The British historian Richard Overy wrote the huge demands of the Four Year Plan "...could not be fully met by a policy of import substitution and industrial rationalisation", thus leading Hitler to decide in November 1937 that to stay ahead in the arms race with the other powers that Germany had to seize Czechoslovakia in the near-future.

[8] The Hossbach conference was largely taken up with an extended discussion about the necessity of bringing areas adjunct to Germany under German economic control, by force if necessary, as Hitler argued that this was the best way to win the arms race.

[8] Overy wrote about Hitler's attitude to the Reich's economic problems that: "He simply saw war instrumentally, as the Japanese had done in Manchuria, as a way to expand the German resource base and to secure it against other powers".

Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on 28 March 1938, where he was instructed to raise demands unacceptable to the Czechoslovak government led by president Edvard Beneš.

Reflecting the spread of modern Ukrainian national consciousness, the pro-Ukrainian faction, led by Avhustyn Voloshyn, gained control of the local government and Subcarpathian Ruthenia was renamed Carpatho-Ukraine.

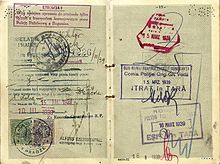

Part of the funds were allocated to help resettle Czechs and Slovaks who had fled from territories lost to Germany, Hungary, and Poland in the Munich Agreement or the Vienna Arbitration Award.

[18] In November 1938, Emil Hácha, who succeeded Beneš, was elected president of the federated Second Republic, renamed Czecho-Slovakia and consisting of three parts: Bohemia and Moravia, Slovakia, and Carpatho-Ukraine.

Without the natural defensive barrier of the mountains of the Sudetenland, Hácha carried out a foreign policy that was slavishly pro-German as he felt this was the best way to preserve his nation's independence.

[19] In late 1938-early 1939, the continuing economic crisis caused by problems of rearmament, especially the shortage of foreign hard currencies needed to pay for raw materials Germany lacked together with reports from Hermann Göring that the Four Year Plan was hopelessly behind schedule forced Hitler in January 1939 to reluctantly order major defense cuts with the Wehrmacht having its steel allocations cut by 30%, aluminum 47%, cement 25%, rubber 14% and copper 20%.

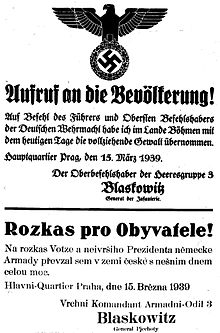

Von Ribbentrop testified at the Nuremberg trials that during this meeting, Hácha had told him that "he wanted to place the fate of the Czech State in the Führer's hands.

"[26][27] According to Joachim Fest, Hácha suffered a heart attack induced by Hermann Göring's threat to bomb the capital and by four o'clock he contacted Prague, effectively "signing Czechoslovakia away" to Germany.

The British historian Victor Rothwell wrote that the Czechoslovak reserves of gold and hard currency seized in March 1939 were "invaluable in staving off Germany's foreign exchange crisis".

Setting up an artificially high exchange rate between the Czechoslovak koruna and the Reichsmark brought consumer goods to Germans (and soon created shortages in the Czech lands).

[34] The National Union of Employees was remolded in the style of the Nazi pseudo-union, the German Labour Front, to provide free sports events, films, concerts and plays for the workers.

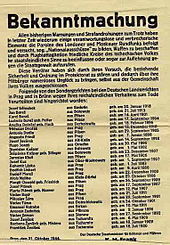

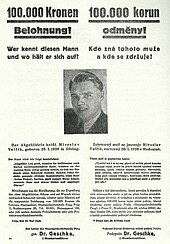

The most important event of the resistance was Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, SS leader Heinrich Himmler's deputy and the then Protector of Bohemia and Moravia.

This is attributed to the view within the Nazi hierarchy that a large swath of the populace was "capable of Aryanization," hence, the Czechs were not subjected to a similar degree of random and organized acts of brutality that their Polish counterparts experienced.

"[40] A paradox of German policy was that the collaborators such as Hácha were held in contempt by the Nazis as "riff raff" while those who clung most defiantly to their sense of Czech identity were considered to be the better subjects of Germanizaton.

[41] Heydrich in a report to Berlin stated that Hácha was "incapable of Germanization" as "he is always sick, arrives with a trembling voice and attempts to evoke pity that demands our mercy".

[41] Aside from the inconsistency of animosity towards Slavs,[42] there is also the fact that the forceful but restrained policy in Czechoslovakia was partly driven by the need to keep the population nourished and complacent so that it can carry out the vital work of arms production in the factories.

After World War II broke out, a Czechoslovak national committee was constituted in France, and under Beneš's presidency sought international recognition as the exiled government of Czechoslovakia.

This attempt led to some minor successes, such as the French-Czechoslovak treaty of 2 October 1939, which allowed for the reconstitution of the Czechoslovak army on French territory, yet full recognition was not reached.

The success of Operation Anthropoid—which resulted in the British-backed assassination of one of Hitler's top henchmen, Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia Reinhard Heydrich, by Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš on 27 May—influenced the Allies in this repudiation.

Beneš worked to bring Czechoslovak communist exiles in Britain into cooperation with his government, offering far-reaching concessions, including the nationalization of heavy industry and the creation of local people's committees at the war's end.

On 21 September, Czechoslovak troops formed in the Soviet-liberated village, Kalinov, which was the first liberated settlement of Slovakia, located near the Dukla Pass in northeastern part of the country.

The delegation was to mobilize the liberated local population to form a Czechoslovak army and to prepare for elections in cooperation with recently established national committees.

In July, Czechoslovak representatives addressed the Potsdam Conference (the U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union) and presented plans for a "humane and orderly transfer" of the Sudeten German population.

[53] The joint Czech-German commission of historians stated in 1996 the following numbers: The deaths caused by violence and abnormal living conditions amount to approximately 10,000 persons killed.