Neferneferuaten

Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure/Waenre/Aten Neferneferuaten (Ancient Egyptian: nfr-nfrw-jtn)[citation needed] was a name used to refer to a female king who reigned toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

If this person is Nefertiti ruling as sole king, it has been theorized by Egyptologist and archaeologist Zahi Hawass that her reign was marked by the fall of Amarna and relocation of the capital back to the traditional city of Thebes.

Simultaneously, Neferneferuaten obtained another epithet, Axt-n-H(j)=s, "One Who is Beneficial for Her Husband", which Gabolde used to prove this king's female identity beyond doubt...

Manetho was an Egyptian priest who lived in the third century BC during the time of the Ptolemies, a thousand years after the Amarna Period of the Eighteenth Dynasty when this woman would have been king.

Manetho's Epitome, a summary of his work, describes the late Eighteenth Dynasty succession as Orus or "Amenophis for 30 years 10 months.

Akhenaten is not even mentioned in the most accurate 18th dynasty king list of Manetho's Epitome of Aegyptiaca compiled by Josephus in Contra Apionem.

[14]Nicholas Reeves sees this graffito as a sign of a "new phase" of the Amarna revolution, with Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten "taking a decidedly softer line" toward the Amun priesthood.

These include: The clues may point to a female coregent, but the unique situation of succeeding kings using identical throne names may have resulted in a great deal of confusion.

[19][20] For some time the accepted interpretation of the evidence was that Smenkhkare served as coregent with Akhenaten beginning about year 15 using the throne name Ankhkheperure.

Things remained in this state of interpretation until the early 1970s when English Egyptologist John Harris noted in a series of papers the existence of versions of the first cartouche that seemed to include feminine indicators.

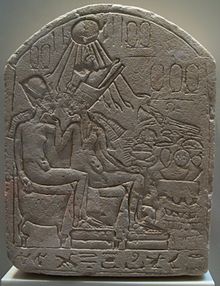

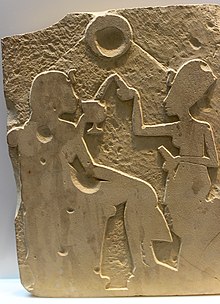

[24] These were linked with a few items including a statuette found in Tutankhamun's tomb depicting a king whose appearance was particularly feminine, even for Amarna art that seems to favor androgyny.

[2] He suggests that adoption of the throne name Ankhkheperure by Smenkhkare was "to emphasize the legitimacy of Smenkh-ka-re's claim against that of Akhenaton's "chosen" (/mr/) coregent".

This was offered as a simple and logical reading of the evidence to explain the nature of the epithets, the use of identical prenomens by successive kings and that she was denied a royal burial.

Akhenaten was left with two royal wives (Nefertiti and Meritaten) and one possible future successor, who was still too young to reign (Tutankhaten).

Nefertiti, who already played an important role in Amarna, and already bore the name Neferneferuaten, is in my view the most likely candidate for this function....After her husband's death, Nefertiti would reign the country herself..[31]The Egyptologists, Rolf Krauss[32] and Nozomu Kawai both assign the female king Neferneferuaten an independent reign of between 2 and 3 years between Akhenaten and Tutankhamun.

[33] Athena Van Der Perre writes: The attestations of the name confirm the reign of Neferneferuaten, which, if this was Nefertiti, could not have started until after the 1st month of the 16th year of Akhenaten, as has been shown in the quarry inscription at Deir Abū Ḥinnis.

[36] Many Egyptologists believe she also served as coregent on the basis of the stela and epithets, although a sole reign seems very likely, given that the Pairi inscription is dated using her regnal years.

[41] The core premise is that her prominence and power in the Amarna Period was almost unprecedented for a great royal wife, which makes her the most likely and most able female to succeed Akhenaten.

However, she is now known to have still been alive in the second to last year of Akhenaten's reign and still bearing the title of Great Royal Wife, based on an ink inscription dated explicitly to 'Year 16 III Akhet day 15' in a limestone quarry at Dayr Abū Ḥinnis.

[47] He proposes that Neferneferuaten helped guide the reformation in the early years of Tutankhaten and conjectures that the return to the dominence of the Amun priesthood is the result of her 'rapid adjustment to political reality'.

[48] This is not a view shared by the excavators, who note that sealings and small objects such as bezel rings from many Eighteenth Dynasty royals including Akhenaten, Ay, Queen Tiye, and Horemheb were found,[49] and that "linking Tutankhamun and Neferneferuaten politically, based on the discovery of their names on amphorae at Tell el-Borg, is unwarranted.

[57] Evidence put forward to suggest she predeceased Akhenaten includes pieces of an ushabti indicating her title at death was Great Royal Wife; wine dockets from her estate declining and ceasing after Year 13;[58] Meritaten's title as Great Royal Wife alongside Akhenaten's name on items from Tutankhamun's tomb indicating she likely replaced Nefertiti in that role; the floor of the tomb intended for her shows signs of cuts being started for the final placement of her sarcophagus.

She had been put forth by Rolf Krauss in 1973 to explain the feminine traces in the prenomen and epithets of Ankhkheperure and to conform to Manetho's description of a Akenkheres as a daughter of Oros.

[51] Most recently, Gabolde has proposed that Meritaten was raised to coregent of Akhenaten during the final years of his reign and that she succeeds him as interregnum regent using the name Ankhkheperure.

Cases have been made for her being the former Nefertiti (Harris, Samson and others), Meryetaten (Krauss 1978; Gabolde 1998) and most recently Neferneferuaten-tasherit, [the] fourth daughter of Akheneten (Allen 2006).

She is thought to have been about ten at the time of Akhenaten's death,[70] but Allen suggests that some daughters may have been older than generally calculated based on their first depicted appearance.

According to Nicholas Reeves, almost 80% of Tutankhamun's burial equipment was derived from Neferneferuaten's original funerary goods, including the famous gold mask, middle coffin, canopic coffinettes, several of the gilded shrine panels, the shabti-figures, the boxes and chests, the royal jewelry, etc.,[74][75] and adapted for use after his unexpected early death.

With so much evidence expunged, first by Neferneferuaten's successor, then the entire Amarna Period by Horemheb, and later in earnest by the kings of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the exact details of events may never be known.

Neferneferuaten's identity and legacy is a key part of the archaeological topics in Jacqueline Benson's 2024 historical fantasy novel, Tomb of the Sun King.

James Allen's previous work in this area primarily dealt with establishing the female gender of Neferneferuaten and then as an individual apart from Smenkhkare.