Neural correlates of consciousness

The neural correlates of consciousness (NCC) are the minimal set of neuronal events and mechanisms sufficient for the occurrence of the mental states to which they are related.

The combination of fine-grained neuronal analysis in animals with increasingly more sensitive psychophysical and brain imaging techniques in humans, complemented by the development of a robust theoretical predictive framework, will hopefully lead to a rational understanding of consciousness, one of the central mysteries of life.

Research has shown a correlation between significant measurable changes in brain structure at the end of the second trimester, which facilitate the emergence of early consciousness in the fetus.

These structural developments include the maturation of neural connections and the formation of key brain regions associated with sensory processing and emotional regulation.

This early stage of consciousness is crucial, as it lays the foundation for later cognitive and social development, influencing how individuals will interact with the world around them after birth.

To be conscious of anything the brain must be in a relatively high state of arousal (sometimes called vigilance), whether in wakefulness or REM sleep, vividly experienced in dreams although usually not remembered.

Brain arousal level fluctuates in a circadian rhythm but may be influenced by lack of sleep, drugs and alcohol, physical exertion, etc.

Yet in REM sleep there is a characteristic atonia, low motor arousal and the person is difficult to wake up, but there is still high metabolic and electric brain activity and vivid perception.

Many nuclei with distinct chemical signatures in the thalamus, midbrain and pons must function for a subject to be in a sufficient state of brain arousal to experience anything at all.

Conversely, it is likely that the specific content of any particular conscious sensation is mediated by particular neurons in the cortex and their associated satellite structures, including the amygdala, thalamus, claustrum and the basal ganglia.

In this manner the neural mechanisms that respond to the subjective percept rather than the physical stimulus can be isolated, permitting visual consciousness to be tracked in the brain.

Logothetis and colleagues[16] recorded a variety of visual cortical areas in awake macaque monkeys performing a binocular rivalry task.

The distribution of the switching times and the way in which changing the contrast in one eye affects these leaves little doubt that monkeys and humans experience the same basic phenomenon.

A number of fMRI experiments that have exploited binocular rivalry and related illusions to identify the hemodynamic activity underlying visual consciousness in humans demonstrate quite conclusively that activity in the upper stages of the ventral pathway (e.g., the fusiform face area and the parahippocampal place area) as well as in early regions, including V1 and the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), follow the percept and not the retinal stimulus.

[22][23] Single-neuron recordings in the medial temporal lobe of epilepsy patients during flash suppression likewise demonstrate abolishment of response when the preferred stimulus is present but perceptually masked.

[27] Impaired consciousness in epileptic seizures of the temporal lobe was likewise accompanied by a decrease in cerebral blood flow in frontal and parietal association cortex and an increase in midline structures such as the mediodorsal thalamus.

These nuclei – three-dimensional collections of neurons with their own cyto-architecture and neurochemical identity – release distinct neuromodulators such as acetylcholine, noradrenaline/norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine and orexin/hypocretin to control the excitability of the thalamus and forebrain, mediating alternation between wakefulness and sleep as well as general level of behavioral and brain arousal.

A feature that distinguishes humans from most animals is that we are not born with an extensive repertoire of behavioral programs that would enable us to survive on our own ("physiological prematurity").

Take, as an example, the incredible fine motor skills exerted in playing a Beethoven piano sonata or the sensorimotor coordination required to ride a motorcycle along a curvy mountain road.

Seemingly complex visual processing (such as detecting animals in natural, cluttered scenes) can be accomplished by the human cortex within 130–150 ms,[40][41] far too brief for eye movements and conscious perception to occur.

It is quite plausible that such behaviors are mediated by a purely feed-forward moving wave of spiking activity that passes from the retina through V1, into V4, IT and prefrontal cortex, until it affects motorneurons in the spinal cord that control the finger press (as in a typical laboratory experiment).

Conversely, conscious perception is believed to require more sustained, reverberatory neural activity, most likely via global feedback from frontal regions of neocortex back to sensory cortical areas[21] that builds up over time until it exceeds a critical threshold.

Struck with the elegance of SS Stevens approach of magnitude estimation, Mountcastle's group discovered three different modalities of somatic sensation shared one cognitive attribute: in all cases the firing rate of peripheral neurons was linearly related to the strength of the percept elicited.

More recently, Ken H. Britten, William T. Newsome, and C. Daniel Salzman have shown that in area MT of monkeys, neurons respond with variability that suggests they are the basis of decision making about direction of motion.

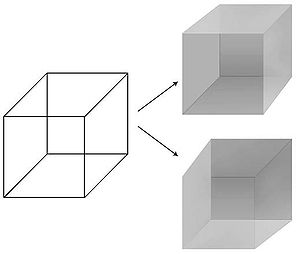

Many of these studies employ perceptual illusions as a way to dissociate sensations (i.e., the sensory information that the brain receives) from perceptions (i.e., how the consciousness interprets them).

Another set of experiments using binocular rivalry in humans showed that certain layers of the cortex can be excluded as candidates of the neural correlate of consciousness.

Francis Crick wrote a popular book, "The Astonishing Hypothesis", whose thesis is that the neural correlate for consciousness lies in our nerve cells and their associated molecules.

Crick and his collaborator Christof Koch[44] have sought to avoid philosophical debates that are associated with the study of consciousness, by emphasizing the search for "correlation" and not "causation".

[needs update] There is much room for disagreement about the nature of this correlate (e.g., does it require synchronous spikes of neurons in different regions of the brain?