Receptor (biochemistry)

In biochemistry and pharmacology, receptors are chemical structures, composed of protein, that receive and transduce signals that may be integrated into biological systems.

[1] These signals are typically chemical messengers[nb 1] which bind to a receptor and produce physiological responses such as change in the electrical activity of a cell.

For example, GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, inhibits electrical activity of neurons by binding to GABAA receptors.

The structures and actions of receptors may be studied by using biophysical methods such as X-ray crystallography, NMR, circular dichroism, and dual polarisation interferometry.

One measure of how well a molecule fits a receptor is its binding affinity, which is inversely related to the dissociation constant Kd.

The final biological response (e.g. second messenger cascade, muscle-contraction), is only achieved after a significant number of receptors are activated.

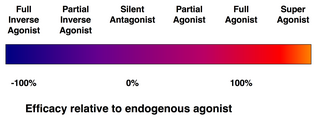

A receptor which is capable of producing a biological response in the absence of a bound ligand is said to display "constitutive activity".

The anti-obesity drugs rimonabant and taranabant are inverse agonists at the cannabinoid CB1 receptor and though they produced significant weight loss, both were withdrawn owing to a high incidence of depression and anxiety, which are believed to relate to the inhibition of the constitutive activity of the cannabinoid receptor.

Ariëns & Stephenson introduced the terms "affinity" & "efficacy" to describe the action of ligands bound to receptors.

[12] Cells can increase (upregulate) or decrease (downregulate) the number of receptors to a given hormone or neurotransmitter to alter their sensitivity to different molecules.

4 examples of intracellular LGIC are shown below: Many genetic disorders involve hereditary defects in receptor genes.

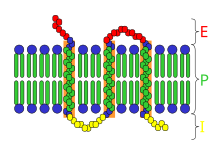

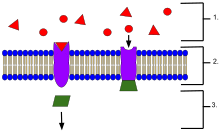

- Ligands, located outside the cell

- Ligands connect to specific receptor proteins based on the shape of the active site of the protein.

- The receptor releases a messenger once the ligand has connected to the receptor.