Neuroscience of music

When the hair cells on the basilar membrane move back and forth due to the vibrating sound waves, they release neurotransmitters and cause action potentials to occur down the auditory nerve.

[2] A widely postulated mechanism for pitch processing in the early central auditory system is the phase-locking and mode-locking of action potentials to frequencies in a stimulus.

Hyde, Peretz and Zatorre (2008) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in their study to test the involvement of right and left auditory cortical regions in the frequency processing of melodic sequences.

Zatorre, Perry, Beckett, Westbury and Evans (1998) examined the neural foundations of AP using functional and structural brain imaging techniques.

AP possessors and non-AP subjects demonstrated similar patterns of left dorsolateral frontal activity when they performed relative pitch judgments.

Studies suggest that individuals are capable of automatically detecting a difference or anomaly in a melody such as an out of tune pitch which does not fit with their previous music experience.

Brattico, Tervaniemi, Naatanen, and Peretz (2006) performed one such study to determine if the detection of tones that do not fit an individual's expectations can occur automatically.

Rhythm, the pattern of temporal intervals within a musical measure or phrase, in turn creates the perception of stronger and weaker beats.

[21] Lastly, the premotor cortex has been shown to be involved in tasks that require the production of relatively complex sequences, and it may contribute to motor prediction.

Studies in animals and humans have established the involvement of parietal, sensory–motor and premotor cortices in the control of movements, when the integration of spatial, sensory and motor information is required.

Another example is the effect of music on movement disorders: rhythmic auditory stimuli have been shown to improve walking ability in Parkinson's disease and stroke patients.

[21] The literature has shown a highly specialized cortical network in the skilled musician's brain that codes the relationship between musical gestures and their corresponding sounds.

[52] Utilizing positron emission tomography (PET), the findings showed that both linguistic and melodic phrases produced activation in almost identical functional brain areas.

Differences were found in lateralization tendencies as language tasks favoured the left hemisphere, but the majority of activations were bilateral which produced significant overlap across modalities.

Jentschke, Koelsch, Sallat and Friederici (2008) conducted a study investigating the processing of music in children with specific language impairments (SLI).

[54] Stewart et al. found that TMS applied to the left frontal lobe disturbs speech but not melody supporting the idea that they are subserved by different areas of the brain.

Krings, Topper, Foltys, Erberich, Sparing, Willmes and Thron (2000) utilized fMRI to study brain area involvement of professional pianists and a control group while performing complex finger movements.

[61] Krings et al. found that the professional piano players showed lower levels of cortical activation in motor areas of the brain.

[75] Herholz, Lappe, Knief and Pantev (2008) investigated the differences in neural processing of a musical imagery task in musicians and non-musicians.

Utilizing magnetoencephalography (MEG), Herholz et al. examined differences in the processing of a musical imagery task with familiar melodies in musicians and non-musicians.

A PET study conducted by Zatorre, Halpern, Perry, Meyer and Evans (1996) investigated cerebral blood flow (CBF) changes related to auditory imagery and perceptual tasks.

CBF increases in the inferior frontal polar cortex and right thalamus suggest that these regions may be related to retrieval and/or generation of auditory information from memory.

Samson and Baird (2009) found that the ability of musicians with Alzheimer's Disease to play an instrument (implicit procedural memory) may be preserved.

Contrasting attended versus unattended instruments, ERP analysis shows subject- and instrument-specific responses including P300 and early auditory components.

This indicates that attention paid to a particular instrument in polyphonic music can be inferred from ongoing EEG, a finding that is potentially relevant for building more ergonomic music-listing based brain-computer interfaces.

This was confirmed by a study by Schlaug et al. in 1995 that found that classical musicians between the ages of 21 and 36 have significantly greater anterior corpora callosa than the non-musical control.

The dystonic guitarists showed significantly more activation of the contralateral primary sensorimotor cortex as well as a bilateral underactivation of premotor areas.

Even in professional musicians, widespread bilateral cortical region involvement is necessary to produce complex hand movements such as scales and arpeggios.

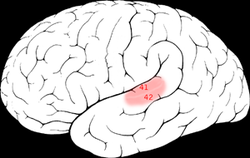

These differences suggest abnormal neuronal development in the auditory cortex and inferior frontal gyrus, two areas which are important in musical-pitch processing.

Gosselin, Peretz, Johnsen and Adolphs (2007) studied S.M., a patient with bilateral damage of the amygdala with the rest of the temporal lobe undamaged and found that S.M.