Neuroscience of sleep

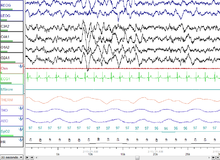

[5] However, the development of improved imaging techniques like EEG, PET and fMRI, along with faster computers have led to an increasingly greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying sleep.

In areas with reduced activity, the brain restores its supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the molecule used for short-term storage and transport of energy.

[12] According to the Hobson & McCarley activation-synthesis hypothesis, proposed in 1975–1977, the alternation between REM and non-REM can be explained in terms of cycling, reciprocally influential neurotransmitter systems.

At a symptomatic level, sleep is characterized by lack of reactivity to sensory inputs, low motor output, diminished conscious awareness and rapid reversibility to wakefulness.

The features defining sleep have been identified for the most part, and like mammals, this includes reduced reaction to sensory input, lack of motor response in the form of antennal immobility, etc.

[52] According to Mander et al., atrophy in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) gray matter is a predictor of disruption in slow activity during NREM sleep that may impair memory consolidation in older adults.

[59][60] The use of imaging modalities like PET, fMRI and MEG, combined with EEG recordings, gives a clue to which brain regions participate in creating the characteristic wave signals and what their functions might be.

Functional paralysis from muscular atonia in REM may be necessary to protect organisms from self-damage through physically acting out scenes from the often-vivid dreams that occur during this stage.

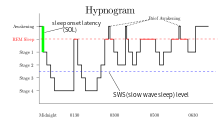

In EEG recordings, REM sleep is characterized by high frequency, low amplitude activity and spontaneous occurrence of beta and gamma waves.

PGO waves have been recorded in the lateral geniculate nucleus and occipital cortex during the pre-REM period and are thought to represent dream content.

The greater signal-to-noise ratio in the LG cortical channel suggests that visual imagery in dreams may appear before full development of REM sleep, but this has not yet been confirmed.

In this relation, some studies have shown that after a sequential motor task, the pre-motor and visual cortex areas involved are most active during REM sleep, but not during NREM.

Further research has shown that the hypothalamic region called ventrolateral preoptic nucleus produces the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA that inhibits the arousal system during sleep onset.

The thalamus also plays a critical role in sleep onset when it changes from tonic to phasic mode, thus acting like a mirror for both central and decentral elements and linking distant parts of the cortex to co-ordinate their activity.

[110][111] With the development of EEG, it was found that the brain has almost continuous internal activity during sleep, leading to the idea that the function could be that of reorganization or specification of neuronal circuits or strengthening of connections.

The short term consequences include increased stress responsivity and psychosocial issues such as impaired cognitive or academic performance and depression.

Experiments indicated that, in healthy children and adults, episodes of fragmented sleep or insomnia increased sympathetic activation, which can disrupt mood and cognition.

The long term consequences include metabolic issues such as glucose homeostasis disruption and even tumor formation and increased risks of cancer.

Therefore, circadian regulation is more than sufficient to explain periods of activity and quiescence that are adaptive to an organism, but the more peculiar specializations of sleep probably serve different and unknown functions.

[117][118] Such mechanisms, which remain under preliminary research as of 2017, indicate potential ways in which sleep is a regulated maintenance period for brain immune functions and clearance of beta-amyloid, a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.

For example, cortisol, which is essential for metabolism (it is so important that animals can die within a week of its deficiency) and affects the ability to withstand noxious stimuli, is increased by waking and during REM sleep.

[139][140] This assumption is based on the active system consolidation hypothesis, which states that repeated reactivations of newly encoded information in hippocampus during slow oscillations in NREM sleep mediate the stabilization and gradually integration of declarative memory with pre-existing knowledge networks on the cortical level.

In doing so, the resource demands can be lessened, since the upkeep and strengthening of synaptic connections constitutes a large portion of energy consumption by the brain and tax other cellular mechanisms such as protein synthesis for new channels.

[126][150] Without a mechanism like this taking place during sleep, the metabolic needs of the brain would increase over repeated exposure to daily synaptic strengthening, up to a point where the strains become excessive or untenable.

[151] Sleep deprivation is common and sometimes even necessary in modern societies because of occupational and domestic reasons like round-the-clock service, security or media coverage, cross-time-zone projects etc.

[163][54][164][56][165][167] Furthermore, RBD has been also highlighted as a strong precursor of future development of those neurodegenerative diseases over several years in prior, which seems to be a great opportunity for improving treatments.

[168] As well as in PD population, insomnia and hypersomnia are frequently recognized in AD patients, which are associated with accumulation of Beta-amyloid, circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD) and melatonin alteration.

[168] The poorly sleep onset in AD has been also associated with dream-related hallucination, increased restlessness, wandering and agitation, that seem to be related with sundowning - a typical chronobiological phenomenon presented in the disease.

[56][167][168] Therefore, a deeper understanding of the relationship between sleep disorders and neurodegenerative diseases seems to be extremely important, mainly considering the limited research related to it and the increasing expectancy of life.

From an evolutionary standpoint, dreams might simulate and rehearse threatening events, that were common in the organism's ancestral environment, hence increasing a person's ability to tackle everyday problems and challenges in the present.