Neutrino astronomy

Because of this, neutrinos offer a unique opportunity to observe processes that are inaccessible to optical telescopes, such as reactions in the Sun's core.

Neutrinos can also offer a very strong pointing direction compared to charged particle cosmic rays.

In order to detect neutrinos, scientists have to shield the detectors from cosmic rays, which can penetrate hundreds of meters of rock.

The resulting nuclear reaction produces secondary particles traveling at high speeds that give off a blue light called Cherenkov radiation.

One was led by Frederick Reines who operated a liquid scintillator - the Case-Witwatersrand-Irvine or CWI detector - in the East Rand gold mine in South Africa at an 8.8 km water depth equivalent.

[6] The other was a Bombay-Osaka-Durham collaboration that operated in the Indian Kolar Gold Field mine at an equivalent water depth of 7.5 km.

[7] Although the KGF group detected neutrino candidates two months later than Reines CWI, they were given formal priority due to publishing their findings two weeks earlier.

[8] In 1968, Raymond Davis, Jr. and John N. Bahcall successfully detected the first solar neutrinos in the Homestake experiment.

[9] Davis, along with Japanese physicist Masatoshi Koshiba were jointly awarded half of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics "for pioneering contributions to astrophysics, in particular for the detection of cosmic neutrinos (the other half went to Riccardo Giacconi for corresponding pioneering contributions which have led to the discovery of cosmic X-ray sources).

"[10] The first generation of undersea neutrino telescope projects began with the proposal by Moisey Markov in 1960 "...to install detectors deep in a lake or a sea and to determine the location of charged particles with the help of Cherenkov radiation.

[12] AMANDA (Antarctic Muon And Neutrino Detector Array) used the 3 km thick ice layer at the South Pole and was located several hundred meters from the Amundsen-Scott station.

[8][12] An example of an early neutrino detector is the Artyomovsk Scintillation Detector [ru] (ASD), located in the Soledar Salt Mine in Ukraine at a depth of more than 100 m. It was created in the Department of High Energy Leptons and Neutrino Astrophysics of the Institute of Nuclear Research of the USSR Academy of Sciences in 1969 to study antineutrino fluxes from collapsing stars in the Galaxy, as well as the spectrum and interactions of muons of cosmic rays with energies up to 10 ^ 13 eV.

A feature of the detector is a 100-ton scintillation tank with dimensions on the order of the length of an electromagnetic shower with an initial energy of 100 GeV.

It consists of 12 strings, each carrying 25 "storeys" equipped with three optical modules, an electronic container, and calibration devices down to a maximum depth of 2475 m.[12] NEMO (NEutrino Mediterranean Observatory) was pursued by Italian groups to investigate the feasibility of a cubic-kilometer scale deep-sea detector.

[8][12] The NESTOR Project was installed in 2004 to a depth of 4 km and operated for one month until a failure of the cable to shore forced it to be terminated.

[8][12] The second generation of deep-sea neutrino telescope projects reach or even exceed the size originally conceived by the DUMAND pioneers.

[14] Both KM3NeT and GVD have completed at least part of their construction[14][15] and it is expected that these two along with IceCube will form a global neutrino observatory.

This is the first time that a neutrino detector has been used to locate an object in space and that a source of cosmic rays has been identified.

These findings in a well-known object are expected to help study the active nucleus of this galaxy, as well as serving as a baseline for future observations.

[19][20] In June 2023, astronomers reported using a new technique to detect, for the first time, the release of neutrinos from the galactic plane of the Milky Way galaxy.

A famous example is that anti-electron neutrinos can interact with a nucleus in the detector by inverse beta decay and produce a positron and a neutron.

[25] To observe neutrino interactions, detectors use photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) to detect individual photons.

[30] There are currently goals to detect neutrinos from other sources, such as active galactic nuclei (AGN), as well as gamma-ray bursts and starburst galaxies.

Seven neutrino experiments (Super-K, LVD, IceCube, KamLAND, Borexino, Daya Bay, and HALO) work together as the Supernova Early Warning System (SNEWS).

If two or more of SNEWS detectors observe a coincidence of an increased flux of neutrinos, an alert is sent to professional and amateur astronomers to be on the lookout for supernova light.

By using the distance between detectors and the time difference between detections, the alert can also include directionality as to the supernova's location in the sky.

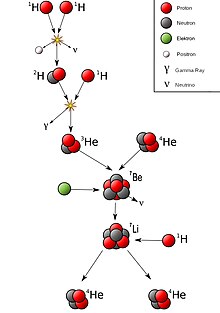

The first is the Proton-Proton (PP) chain, in which protons are fused together into helium, sometimes temporarily creating the heavier elements of lithium, beryllium, and boron along the way.

Therefore, by detecting the anti-neutrino flux as a function of energy, we can obtain the relative compositions of these elements and set a limit on the total power output of Earth's geo-reactor.

The interaction probability will depend on the number of nucleons the neutrino passed along its path, which is directly related to density.

[35] These high-energy neutrinos are either the primary or secondary cosmic rays produced by energetic astrophysical processes.