Neutron–proton ratio

In particular, most pairs of protons in large nuclei are not far enough apart, such that electrical repulsion dominates over the strong nuclear force, and thus proton density in stable larger nuclei must be lower than in stable smaller nuclei where more pairs of protons have appreciable short-range nuclear force attractions.

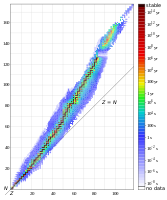

For many elements with atomic number Z small enough to occupy only the first three nuclear shells, that is up to that of calcium (Z = 20), there exists a stable isotope with N/Z ratio of one.

The exceptions are beryllium (N/Z = 1.25) and every element with odd atomic number between 9 and 19 inclusive (though in those cases N = Z + 1 always allows for stability).

Radioactive decay generally proceeds so as to change the N/Z ratio to increase stability.

If the N/Z ratio is greater than 1, alpha decay increases the N/Z ratio, and hence provides a common pathway towards stability for decays involving large nuclei with too few neutrons.

From the liquid drop model, this bonding energy is approximated by empirical Bethe–Weizsäcker formula Given a value of

This nuclear physics or atomic physics–related article is a stub.