Ancient Greek comedy

A burlesque dramatic form that blended tragic and comic elements, known as phlyax play or hilarotragedy, developed in the Greek colonies of Magna Graecia by the late 4th century BC.

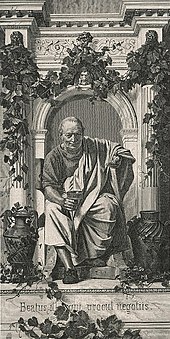

The philosopher Aristotle wrote in his Poetics (c. 335 BC) that comedy is a representation of laughable people and involves some kind of blunder or ugliness which does not cause pain or disaster.

Aristophanes lampooned the most important personalities and institutions of his day, as can be seen, for example, in his buffoonish portrayal of Socrates in The Clouds, and in his racy anti-war farce Lysistrata.

He was one of a large number[clarification needed] of comic poets working in Athens in the late 5th century, his most important contemporary rivals being Hermippus and Eupolis.

Stock characters of all sorts also emerge: courtesans, parasites, revellers, philosophers, boastful soldiers, and especially the conceited cook with his parade of culinary science.

[7] The satirical and farcical element which featured so strongly in Aristophanes' comedies was increasingly abandoned, the de-emphasis of the grotesque—whether in the form of choruses, humour or spectacle—opening the way for greater representation of daily life and the foibles of recognisable character types.

[8] Apart from Diphilus, the New Comedians preferred the everyday world to mythological themes, coincidences to miracles or metamorphoses; and they peopled this world with a whole series of semi-realistic, if somewhat stereotypical figures,[8] who would become the stock characters of Western comedy: braggarts, the permissive father figure and the stern father (senex iratus), young lovers, parasites, kind-hearted prostitutes, and cunning servants.

[9] Their largely gentle comedy of manners drew on a vast array of dramatic devices, characters and situations their predecessors had developed: prologues to shape the audience's understanding of events, messengers' speeches to announce offstage action, descriptions of feasts, the complications of love, sudden recognitions, ex machina endings were all established techniques which playwrights exploited and evoked.

[citation needed] In his own time, Philemon was perhaps the most successful among the New Comedy, regularly beating the younger figure of Menander in contests; but the latter would be the most highly esteemed by subsequent generations.

[18] The New Comedy influenced much of Western European literature, primarily through Plautus and Terence: in particular the comic drama of Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, Congreve, and Wycherley,[19] and, in France, Molière.