Lynching in the United States

In the 17th century, in the context of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the British Isles and unsettled social and political conditions in the American colonies, lynchings became a frequent form of "mob justice" when the authorities were perceived as untrustworthy.

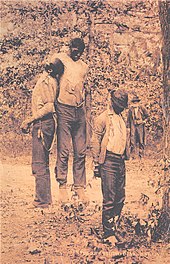

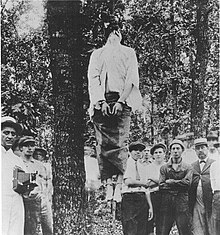

[9] At the first recorded lynching, in St. Louis in 1835, a Black man named McIntosh (who killed a deputy sheriff while being taken to jail) was captured, chained to a tree, and burned to death on a corner lot downtown in front of a crowd of more than 1,000 people.

[10] According to historian Michael J. Pfeifer, the prevalence of lynchings in post–Civil War America reflected people's lack of confidence in the "due process" of the U.S. judicial system.

[28] Tuskegee Institute's method of categorizing most lynching victims as either Black or white in publications and data summaries meant that the murders of some minority and immigrant groups were obscured.

In earlier years, Whites who were subject to lynching were often targeted because of suspected political activities or support of freedmen, but they were generally considered members of the community in a way new immigrants were not.

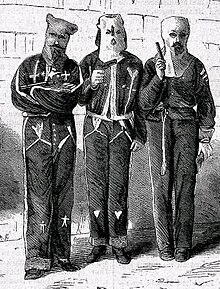

Secret vigilante and terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) instigated extrajudicial assaults and killings in order to discourage freedmen from voting, working, and getting educated.

Lynchings to prevent freedmen and their allies from voting and bearing arms were extralegal ways of trying to enforce the previous system of social dominance and the Black Codes, which had been invalidated by the 14th and 15th Amendments in 1868 and 1870.

[51] The frequency of lynchings rose during years of poor economy and low prices for cotton, demonstrating that more than social tensions generated the catalysts for mob action against the underclass.

[52] Henry Smith, an African-American handyman accused of murdering a policeman's daughter, was a noted lynching victim because of the ferocity of the attack against him and the huge crowd that gathered.

[55] In Duluth, Minnesota, on June 15, 1920, three young African-American traveling circus workers were lynched after having been accused of having raped a white woman and were jailed pending a grand jury hearing.

[57] D. W. Griffith's 1915 film, The Birth of a Nation, glorified the original Ku Klux Klan as protecting white southern women during Reconstruction, which he portrayed as a time of violence and corruption, following the Dunning School's interpretation of history.

[97] African-American women's clubs raised funds and conducted petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings, and demonstrations to highlight the issues and combat lynching.

[98] In the great migration, particularly from 1910 to 1940, 1.5 million African Americans left the South, primarily for destinations in northern and mid-western cities, both to gain better jobs and education and to escape the high rate of violence.

A mob destroyed his printing press and business, ran Black leaders out of town and killed many others, and overturned the biracial Populist-Republican city government, headed by a white mayor and majority-white council.

[102] In 1904, Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, published an article in the magazine North American Review to respond to Southerner Thomas Nelson Page.

The pledge included the statement: In light of the facts we dare no longer to... allow those bent upon personal revenge and savagery to commit acts of violence and lawlessness in the name of women.

Its passage was blocked by White Democratic senators from the Solid South, the only representatives elected since the southern states had disfranchised African Americans around the start of the 20th century.

Florida constable Tom Crews was sentenced to a $1,000 fine (equivalent to $15,600 in 2023) and one year in prison for civil rights violations in the killing of an African-American farm worker.

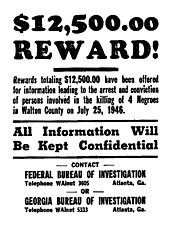

In 1946, a mob of white men shot and killed two young African-American couples near Moore's Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia, 60 miles east of Atlanta.

Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out, and he was shot in the head before being thrown into the Tallahatchie River, his body weighed down with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire.

The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the Black community throughout the U.S.[137] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-white jury.

In 2005, 80-year-old Edgar Ray Killen, one of the men who had earlier gone free, was retried by the state of Mississippi, convicted of three counts of manslaughter in a new trial, and sentenced to 60 years in prison.

[144] The resolution expressed "the deepest sympathies and most solemn regrets of the Senate to the descendants of victims of lynching, the ancestors of whom were deprived of life, human dignity and the constitutional protections accorded all citizens of the United States".

[145] A number of nooses appeared in 2017, primarily in or near Washington, D.C.[146][147][148] In August 2014, Lennon Lacy, a teenager from Bladenboro, North Carolina, who had been dating a white girl, was found dead, hanging from a swing set.

[159][160] The San Francisco Vigilance Movement has traditionally been portrayed as a positive response to government corruption and rampant crime, but revisionist historians have argued that it created more lawlessness than it eliminated.

[175] In the South, Blacks generally were not able to serve on juries, as they could not vote, having been disfranchised by discriminatory voter registration and electoral rules passed by majority-white legislatures in the late 19th century, who also imposed Jim Crow laws.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr. succeeded in gaining House passage of an anti-lynching bill, but it was defeated in the Senate, still dominated by the Southern Democratic bloc, supported by its disfranchisement of Blacks.

[181][182][183] House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer criticized Rand Paul's position, saying on Twitter that "it is shameful that one GOP Senator is standing in the way of seeing this bill become law."

[188][189] Virginia passed anti-lynching legislation, which was signed on March 14, 1928 by Governor Harry F. Byrd following a media campaign by Norfolk Virginian-Pilot editor Louis Isaac Jaffe against mob violence.

[198] In 2010, the South Carolina Sentencing Reform Commission voted to rename the law "assault and battery by a mob", and to soften consequences for situations in which no one was killed or seriously injured in an attack by two or more people on a single victim.