New Journalism

The subjective nature of New Journalism received extensive exploration: one critic suggested the genre's practitioners functioned more as sociologists and psychoanalysts than as journalists.

[3] Ault and Emery, for instance, said "[i]ndustrialization and urbanization changed the face of America during the latter half of the Nineteenth century, and its newspapers entered an era known as that of the 'New Journalism.

'"[4] John Hohenberg, in The Professional Journalist (1960), called the interpretive reporting which developed after World War II a "new journalism which not only seeks to explain as well as to inform; it even dares to teach, to measure, to evaluate.

[9] Matthew Arnold is credited with coining the term "New Journalism" in 1887,[10][11] which went on to define an entire genre of newspaper history, particularly Lord Northcliffe's turn-of-the-century press empire.

[23] Rarely mentioned, perhaps because they are somewhat less playfully countercultural in tone, as early and eminent exemplars of the new form are: Hannah Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem"[24], John Hersey's "Hiroshima"[25], and Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring";[26] articles which respectively introduced the Holocaust, nuclear war, and the existential threat of mass extinction into public consciousness for the first time for most of their contemporary readers.

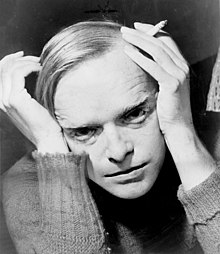

[32] The first of the new breed of nonfiction writers to receive wide notoriety was Truman Capote,[33] whose 1965 best-seller, In Cold Blood, was a detailed narrative of the murder of a Kansas farm family.

[33] Wolfe's The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, whose introduction and title story, according to James E. Murphy, "emerged as a manifesto of sorts for the nonfiction genre,"[33] was published the same year.

In his introduction,[36] Wolfe wrote that he encountered trouble fashioning an Esquire article out of material on a custom car extravaganza in Los Angeles, in 1963.

Finding he could not do justice to the subject in magazine article format, he wrote a letter to his editor, Byron Dobell, which grew into a 49-page reportb detailing the custom car world, complete with scene construction, dialogue and flamboyant description.

[37] A review by Jack Newfield of Dick Schaap's Turned On saw the book as a good example of budding tradition in American journalism which rejected many of the constraints of conventional reporting: This new genre defines itself by claiming many of the techniques that were once the unchallenged terrain of the novelist: tension, symbol, cadence, irony, prosody, imagination.

[40]Seymour Krim's Shake It for the World, Smartass, which appeared in 1970, contained "An Open Letter to Norman Mailer"[41] which defined New Journalism as "a free nonfictional prose that uses every resource of the best fiction.

[46] David McHam, in an article titled "The Authentic New Journalists", distinguished the nonfiction reportage of Capote, Wolfe and others from other, more generic interpretations of New Journalism.

[47] Also in 1971, William L. Rivers disparaged the former and embraced the latter, concluding, "In some hands, they add a flavor and a humanity to journalistic writing that push it into the realm of art.

[53] In contrast to a conventional journalistic striving for an objectivity, subjective journalism allows for the writer's opinion, ideas or involvement to creep into the story.

In another 1971 article under the same title, Ridgeway called the counterculture magazines such as The New Republic and Ramparts and the American underground press New Journalism.

[16] Critical comment dealing with New Journalism as a literary-journalistic genre (a distinct type of category of literary work grouped according to similar and technical characteristics[57]) treats it as the new nonfiction.

[59] Stein, for instance, found the key to New Journalism not its fictionlike form but the "saturation reporting" which precedes it, the result of the writer's immersion in his subject.

I contend that it has already proven itself more accurate than traditional journalism—which unfortunately is saying but so much...[62]Wolfe coined "saturation reporting" in his Bulletin of the American Society of Newspaper Editors article.

[17] In Wolfe's Esquire piece, saturation became the "Locker Room Genre" of intensive digging into the lives and personalities of one's subject, in contrast to the aloof and genteel tradition of the essayists and "The Literary Gentlemen in the Grandstand".

[52] Among the most prominent New Journalists, Murphy lists: Jimmy Breslin, Truman Capote, Joan Didion, David Halberstam, Pete Hamill, Larry L. King, Norman Mailer, Joe McGinniss, Rex Reed, Mike Royko, John Sack, Dick Schaap, Terry Southern, Gail Sheehy, Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson, Dan Wakefield and Tom Wolfe.

[52] In The New Journalism, the editors E.W Johnson and Tom Wolfe, include George Plimpton for Paper Lion, Life writer James Mills and Robert Christgau, et cetera, in the corps.

[65][66] Robert Stein believed that "In the New Journalism the eye of the beholder is all—or almost all,"[67] and in 1971 Philip M. Howard, wrote that the new nonfiction writers rejected objectivity in favor of a more personal, subjective reportage.

This is sometimes felt to be egotistical, and the frank identification of the author, especially as the "I" instead of merely the impersonal "eye" is often frowned upon and taken as proof of "subjectivity", which is the opposite of the usual journalistic pretense.

[37]And in spite of the fact that Capote believed in the objective accuracy of In Cold Blood and strove to keep himself totally out of the narrative, one reviewer found in the book the "tendency among writers to resort to subjective sociology, on the other hand, or to super-creative reportage, on the other.

[80] New Yorker writers Renata Adler and Gerald Jonas joined the fray in the Winter 1966 issue of Columbia Journalism Review.

[81] Wolfe himself returned to the affair a full seven years later, devoting the second of his two February New York articles[82] (1972) to his detractors but not to dispute their attack on his factual accuracy.

'"[83] Widely criticized was the technique of the composite character,[83] the most notorious example of which was "Redpants", a presumed prostitute whom Gail Sheehy wrote about in New York in a series on that city's sexual subculture.

"[87] While the practice of journalism had improved during the past fifteen years, he argued, it was because of an influx of good writers notable for unique styles, not because they belonged to any school or movement.

Salinger wrote to Jock Whitney "With the printing of the inaccurate and sub-collegiate and gleeful and unrelievedly poisonous article on William Shawn, the name of the Herald Tribune, and certainly your own will very likely never again stand for anything either respect-worthy or honorable."

White's letter to Whitney, dated "April 1965," contains the following passage: "Tom Wolfe's piece on William Shawn violated every rule of conduct I know anything about.