Newmarket Canal

With a total length of about 10 miles (16 km), it was supposed to connect the town to the Trent–Severn Waterway via the East Holland River and Lake Simcoe.

The project was originally presented as a way to avoid paying increasing rates on the Northern Railway of Canada, which threatened to make business in Newmarket uncompetitive.

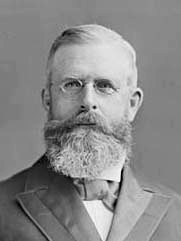

From the start, the real impetus for the project was a way to bring federal money to the riding of York North, which was held by powerful Liberal member William Mulock.

[3] Traffic on this section led William Roe and Andrew Borland to set up a fur trading post under a huge elm tree on the bank of the river at the ending of the War of 1812.

Borland moved on, but Roe stayed in town and set up a new store at the south end of what developed into Main Street, complete with a dock on the river for traders to use.

[3] The town of Newmarket had undergone rapid growth before the start of the 20th century due largely to the efforts of William Mulock, then a sitting member of the Liberal Party of Canada and Wilfrid Laurier's right-hand man in the province.

The remains of these industries are still visible on the local geography; Joseph Hill's lumber mill and later William Cane and Sons factory's mill stock now forms Fairy Lake,[5] the Davis Leather Company's buildings today form the Tannery Mall,[6] and one of the original Office Specialty factory buildings has been converted to lofts just east of Main Street.

It was ultimately completed both for political reasons and as a way to secure water rights for hydroelectricity, the idea of using it as a shipping route was no longer important.

[3] The usefulness of such a route was suspect, given that the northward flow of goods was limited to perhaps 20 short tons (18,000 kg) a day, compared to 40 moving south to Toronto.

[12] Mulock and the mayor of Newmarket, Howard S. Cane,[b] one of the "Sons" of the local factory, met by chance on the train to Toronto in September 1904.

They arrived on 21 February 1905 and found the Prime Minister more than interested in the project, and he noted: ...instead of asking for a post-office or cut-stone building, the first request ever made by the County of York for the expenditure of public money was for the more substantial purpose of enhancing the facilities of transportation of their people for the development of commerce.

[17] He had the Minister for Railways and Canals, Henry Emmerson, order a more complete estimate from Walsh, this time with an eye to reducing the cost as much as possible.

[15] Shortly after taking office, Walsh noted that Butler had spoken "in a contemptuous manner of Sir William Mulock and the Holland River improvements, and expressed himself as thoroughly opposed.

[16] By January 1906, under intense pressure, the Department of Railways and Canals ordered Walsh to present plans for the dredging of the Holland, section 1, as soon as possible.

It was relatively similar to the ad hoc plans presented earlier, based on the 143 by 33 feet (44 m × 10 m) lock size used across the Trent system.

To address the lack of water, Walsh added large piers leading upstream from the locks, forming small lakes at the entrance to each one.

Wilcox, about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south of Aurora, normally empties to the west, ultimately flowing into Lake Ontario via the Humber River.

As if this were not enough, when the original dredging efforts failed and were taken over in May 1908, Grant ordered a new survey of the Holland and came up with the plan of cutting a channel from the eastern to western branches.

His reserved his strongest complaints for the changes to the locks, noting that they would "enormously increase the aggregate cost of the work, lessen the water storage for supply purposes, and substitute not the slightest benefit or advantage in any other respect.

[33] Contract tenders for section 2 were sent out in the spring of 1907, shortly after Emmerson had been replaced by George Perry Graham as Minister of Railways and Canals.

[39] As early as 1905, when it became clear that the project had strong backing within the Liberal establishment and that appealing to reason was not going to work, the Conservatives switched their attacks to the problem of a lack of suitable water supply.

He returned these plans to Butler in September 1908, having also reduced their length back to 143 feet and adopted Walsh's original valve system and eliminating his own lock-side tubes.

These would sit on the bottom of the lock and be raised using winches, held in place by an inflated India rubber bag at the top, and latches at the sides.

The Orillia Packet joked that the builders could dispense with the swing bridges, and people could cross it by simply putting on their rubber boots.

[40] Haughton Lennox, the longtime member for Simcoe South which included Aurora, remained staunchly opposed to the system, and repeatedly spoke out against it in the House.

Thomas George Wallace opposed the motion so he could add an amendment cancelling the canal as "a wanton misuse and waste of public money."

[54]Once again the debate stretched for hours, this time with attacks against a long series of similar Liberal projects across the country, or ones that had been proposed only to be immediately cancelled when a by-election brought a Conservative to that riding.

Bowden, the new chief engineer, replied with a report on 3 January 1912, stating that about 80% of the work was complete on the main portion of the canal, but little of the dredging of the upper Holland had been carried out.

He estimated traffic would be limited to pleasure boats and barges carrying wood to the factories, but the locks and bridges would have to be manned at an annual cost of $4,000, and another $4,000 to run the pumping system that had been introduced to keep the canal full.

The eastern arm runs roughly southward through River Drive Park and into Holland Landing on the west side of town.