Nibelungenlied

The Nibelungenlied is based on an oral tradition of Germanic heroic legend that has some of its origin in historic events and individuals of the 5th and 6th centuries and that spread throughout almost all of Germanic-speaking Europe.

Its legacy today is most visible in Richard Wagner's operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which, however, is mostly based on Old Norse sources.

[22][18] At the same time, the young Siegfried is receiving his courtly education in the Netherlands; he is dubbed a knight and decides that he will go to Worms to ask for Kriemhild as his wife.

Kriemhild only agrees after Etzel's messenger, Margrave Rüdiger von Bechelaren, swears loyalty to her personally and she realizes she can use the Huns to gain revenge on Siegfried's murderers.

Kriemhild then seeks to convince Dietrich von Bern and Hildebrand to attack the Burgundians; they refuse, but Etzel's brother Bloedelin agrees.

[41] This anonymity extends to discussions of literature in other Middle High German works: although it is common practice to judge or praise the poems of others, no other poet refers to the author of the Nibelungenlied.

[45] Although a single Nibelungenlied-poet is often posited, the degree of variance in the text and its background in an amorphous oral tradition mean that ideas of authorial intention must be applied with caution.

Wolfram von Eschenbach references the cook Rumolt, usually taken to be an invention of the Nibelungenlied-poet, in his romance Parzival (c. 1204/5), thereby providing an upper bound on the date the epic must have been composed.

These facts, combined with the dating, have led scholars to believe that Wolfger von Erla, Bishop of Passau (reigned 1191–1204) was the patron of the poem.

German medievalist Jan-Dirk Müller claims that the poem in its written form is entirely new, although he admits the possibility that an orally transmitted epic with relatively consistent contents could have preceded it.

[58] The language of the Nibelungenlied is characterized by its formulaic nature, a feature of oral poetry, meaning that similar or identical words, epithets, phrases, and even lines can be found in various positions throughout the poem.

An acute accent indicates the stressed beat of a metrical foot, and || indicates the caesura: Ze Wórmez bí dem Ríne || si wónten mít ir kráft.

German medievalist Jan-Dirk Müller notes that while it would be typical of a medieval poet to incorporate lines from other works in their own, no stanza of the Nibelungenlied can be proven to have come from an older poem.

[64] The nature of the stanza creates a structure whereby the narrative progresses in blocks: the first three lines carry the story forward, while the fourth introduces foreshadowing of the disaster at the end or comments on events.

This kingdom, under the rule of king Gundaharius, was destroyed by the Roman general Flavius Aetius in 436/437, with survivors resettled in eastern Gaul in a region centered around modern-day Geneva and Lyon (at the time known as Lugdunum).

[82] Scholars such as Otto Höfler have speculated that Siegfried and his slaying of the dragon may be a mythologized reflection of Arminius and his defeat of the Roman legions in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

The Old Norse Atlakviða, a poem likely originally from the ninth century that has been reworked as part of the Poetic Edda, tells the story of the death of the Burgundians without any mention of Sigurd (Siegfried) and can be taken as an attestation for an older tradition.

[74][84] In fact, the earliest attested work to connect Siegfried explicitly with the destruction of the Burgundians is the Nibelungenlied itself, though Old Norse parallels make it clear that this tradition must have existed orally for some time.

[88] More elaborate stories about Siegfried's youth are found in the Thidrekssaga and in the later heroic ballad Das Lied vom Hürnen Seyfrid, both of which appear to preserve German oral traditions about the hero that the Nibelungenlied-poet decided to suppress for their poem.

Earlier (and many later) attestations of Kriemhild outside of the Nibelungenlied portray her as obsessed with power and highlight her treachery to her brothers rather than her love for her husband as her motivation for betraying them.

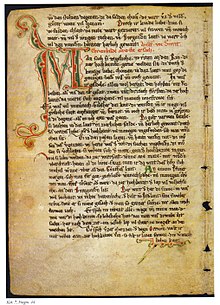

[7] The Ambraser Heldenbuch titles its copy of the Nibelungenlied with "Ditz Puech heysset Chrimhilt" (this book is named "Kriemhild"), showing that she was seen as the most important character.

The earliest attested reception of the Nibelungenlied, the Nibelungenklage, which was likely written only shortly afterwards, shows an attempt both to make sense of the horror of the destruction and to absolve Kriemhild of blame.

[98] The majority of these epics revolve around the hero Dietrich von Bern, who plays a secondary role in the Nibelungenlied: it is likely that his presence there inspired these new poems.

Bodmer dubbed the Nibelungenlied the "German Iliad" ("deutsche Ilias"), a comparison that skewed the reception of the poem by comparing it to the poetics of a classical epic.

Bodmer attempted to make the Nibelungenlied conform more closely to these principles in his own reworkings of the poem, leaving off the first part in his edition, titled Chriemhilden Rache, in order to imitate the in medias res technique of Homer.

[108] Many early supporters sought to distance German literature from French Classicism and belonged to artistic movements such as Sturm und Drang.

This interpretation of the epic continued during the Biedermeier period, during which the heroic elements of the poem were mostly ignored in favor of those that could more easily be integrated into a bourgeois understanding of German virtue.

Especially important for this new understanding of the poem was Richard Wagner's operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which, however, was based almost entirely on the Old Norse versions of the Nibelung saga.

[113] During the Second World War, Hermann Göring would explicitly use this aspect of the Nibelungenlied to celebrate the sacrifice of the German army at Stalingrad and compare the Soviets to Etzel's Asiatic Huns.

However, the majority of popular adaptations of the material today in film, computer games, comic books, etc., are not based on the medieval epic directly.