Nicene Creed

[6] The Nicene Creed is part of the profession of faith required of those undertaking important functions within the Orthodox, Catholic and Lutheran Churches.

[15][8] However, part of it can be found as an "Authorized Affirmation of Faith" in the main volume of the Common Worship liturgy of the Church of England published in 2000.

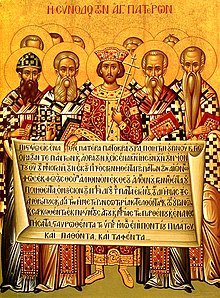

[22] The Nicene Creed was adopted to resolve the Arian controversy, whose leader, Arius, a clergyman of Alexandria, "objected to Alexander's (the bishop of the time) apparent carelessness in blurring the distinction of nature between the Father and the Son by his emphasis on eternal generation".

[23] Emperor Constantine called the Council at Nicaea to resolve the dispute in the church which resulted from the widespread adoption of Arius' teachings, which threatened to destabilize the entire empire.

[27] The Athanasian Creed, formulated about a century later, which was not the product of any known church council and not used in Eastern Christianity, describes in much greater detail the relationship between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The earlier Apostles' Creed, apparently formulated before the Arian controversy arose in the fourth century, does not describe the Son or the Holy Spirit as "God" or as "consubstantial with the Father.

"[27] Thomas Aquinas stated that the phrase for us men, and for our salvation was to refute the error of Origen, "who alleged that by the power of Christ's Passion even the devils were to be set free."

The text ends with anathemas against Arian propositions, preceded by the words: "We believe in the Holy Spirit" which terminates the statements of belief.

[37] Their initial text was probably a local creed from a Syro-Palestinian source into which they inserted phrases to define the Nicene theology.

[43]Since the end of the 19th century,[44] scholars have questioned the traditional explanation of the origin of this creed, which has been passed down in the name of the council, whose official acts have been lost over time.

Though some scholarship claims that hints of the later creed's existence are discernible in some writings,[46] no extant document gives its text or makes explicit mention of it earlier than the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon in 451.

[11][44] The Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus) reaffirmed the original 325 version[c] of the Nicene Creed and declared that "it is unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν) faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicaea" (i.e., the 325 creed).

[50] This question is connected with the controversy whether a creed proclaimed by an ecumenical council is definitive in excluding not only excisions from its text but also additions to it.

[citation needed] In one respect, the Eastern Orthodox Church's received text of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed differs from the earliest text,[51] which is included in the acts of the Council of Chalcedon of 451: The Eastern Orthodox Church uses the singular forms of verbs such as "I believe", in place of the plural form ("we believe") used by the council.

All ancient liturgical versions, even the Greek, differ at least to some small extent from the text adopted by the First Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople.

[citation needed] Although the councils' texts have "Πιστεύομεν [...] ὁμολογοῦμεν [...] προσδοκοῦμεν" ("we believe [...] confess [...] await"), the creed that the Churches of Byzantine tradition use in their liturgy has "Πιστεύω [...] ὁμολογῶ [...] προσδοκῶ" ("I believe [...] confess [...] await"), accentuating the personal nature of recitation of the creed.

The Armenian text has many more additions, and is included as showing how that ancient church has chosen to recite the creed with these numerous elaborations of its contents.

Καὶ εἰς ἕνα Κύριον Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν, τὸν Υἱὸν τοῦ Θεοῦ τὸν μονογενῆ, τὸν ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς γεννηθέντα πρὸ πάντων τῶν αἰώνων· φῶς ἐκ φωτός, Θεὸν ἀληθινὸν ἐκ Θεοῦ ἀληθινοῦ, γεννηθέντα οὐ ποιηθέντα, ὁμοούσιον τῷ Πατρί, δι' οὗ τὰ πάντα ἐγένετο.

[72][73] Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipoténtem, factórem cæli et terræ, visibílium ómnium et invisibílium.

Et in unum Dóminum, Jesum Christum, Fílium Dei unigénitum, et ex Patre natum ante ómnia sǽcula.

Crucifíxus étiam pro nobis sub Póntio Piláto; passus et sepúltus est, et resurréxit tértia die, secúndum Scriptúras, et ascéndit in coelum, sedet ad déxteram Patris.

Et íterum ventúrus est cum glória, judicáre vivos et mórtuos, cujus regni non erit finis.

The implications of the difference in overtones of "ἐκπορευόμενον" and "qui [...] procedit" was the object of the study The Greek and the Latin Traditions regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit published by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity in 1996.

[75] Again, the terms ὁμοούσιον and consubstantialem, translated as "of one being" or "consubstantial", have different overtones, being based respectively on Greek οὐσία (stable being, immutable reality, substance, essence, true nature),[76] and Latin substantia (that of which a thing consists, the being, essence, contents, material, substance).

[77] "Credo", which in classical Latin is used with the accusative case of the thing held to be true (and with the dative of the person to whom credence is given),[78] is here used three times with the preposition "in", a literal translation of the Greek εἰς (in unum Deum [...], in unum Dominum [...], in Spiritum Sanctum [...]), and once in the classical preposition-less construction (unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam).

He suffered, was crucified, was buried, rose again on the third day, ascended into heaven with the same body, [and] sat at the right hand of the Father.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the uncreate and the perfect; Who spoke through the Law, the prophets, and the Gospels; Who came down upon the Jordan, preached through the apostles, and lived in the saints.

Writing in 1971, the Ruthenian scholar Casimir Kucharek noted, "In Eastern Catholic Churches, the Filioque may be omitted except when scandal would ensue.