Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen

Not only did he attend the lectures of the best statistics and economics professors in France, he also immersed himself in the philosophy of science, especially the works of Blaise Pascal, Ernst Mach, and Henri Bergson.

The trip was put off for about a year, however, as he had more pressing obligations in Romania: He needed to conclude his first national editorial project, a 500-page manual on Metoda Statistică, and he had to care for his aging widowed mother who was in bad health.

On arriving at Harvard University, he learned that the Economic Barometer had been shut down years before: The project had completely failed to predict the Wall Street Crash of 1929, and was soon abandoned altogether.

After several failed attempts to find another sponsor for his research, Georgescu-Roegen finally managed a meeting with the professor at the university teaching business cycles to see if there were any other opportunities available to him.

Schumpeter warmly welcomed Georgescu-Roegen to Harvard, and soon introduced him to the now famous 'circle', one of the most remarkable groups of economists ever working at the same institution, including Wassily Leontief, Oskar Lange, Fritz Machlup, and Nicholas Kaldor, among others.

[31]: 132 [14]: 7f In spring 1936, Georgescu-Roegen left the U.S. His voyage back to Romania came to last almost a year in itself, as he paid a long visit to Friedrich Hayek and John Hicks at the London School of Economics on the way home.

A trusted government official and a leading member of an influential political party, Georgescu-Roegen was appointed general secretary of the Armistice Commission, responsible for negotiating the conditions for peace with the occupying power.

Plenty of items on Georgescu-Roegen's track record were suitable for antagonising both the native Romanian communists and the Soviet authorities that still occupied the country: His top membership of the Peasants' Party, in open opposition to the Communist Party; his chief negotiating position in the Armistice Commission, defending Romania's sovereignty against the occupying power; and his earlier affiliation with capitalist US as a Rockefeller research fellow at Harvard University.

Only now, the circumstances were very different from what they had been in the 1930s: He was no longer a promising young scholar on a trip abroad, supported and sponsored by his native country; instead, he was a middle-aged political refugee who had fled a communist dictatorship behind the Iron Curtain.

It has been argued that Georgescu-Roegen's decision to move from Harvard to the permanence and stability of the less prestigious Vanderbilt was motivated by his precarious wartime experiences and his feeling of insecurity as a political refugee in his new country.

Whereas Georgescu-Roegen's own magnum opus went largely unnoticed by mainstream (neoclassical) economists, the report on The Limits to Growth, published in 1972 by the Club of Rome, created something of a stir in the economics profession.

When Georgescu-Roegen delivered a lecture at the University of Geneva in Switzerland in 1974, he made a lasting impression on the young and newly graduated French historian and philosopher Jacques Grinevald.

[45][note 1] Similar to his involvement with the Club of Rome (see above), Georgescu-Roegen's article on Energy and Economic Myths came to play a crucial role in the dissemination of his views among the later followers of the degrowth movement.

[48] No fewer than four Nobel Prize laureates were among the contributing economists;[9]: 150 but none of the colleagues from Georgescu-Roegen's department at Vanderbilt participated, a fact that has since been taken as evidence of his social and academic isolation at the place.

As he likened himself to one unlucky heretic and legendary martyr of science out of the Italian Renaissance, Georgescu-Roegen grumbled and exclaimed: "E pur si muove is ordinarily attributed to Galileo, although those words were the last ones uttered by Giordano Bruno on the burning stake!

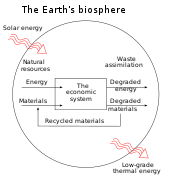

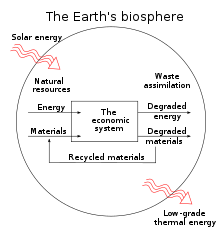

Georgescu-Roegen sees the transformation of energy – whether in nature or in human society – as moving the universe closer towards a final state of inert physical, statistical uniformity and maximum entropy.

[4]: 313 Georgescu-Roegen explains that modern mechanised agriculture has developed historically as a result of the growing pressure of population on arable land; but the relief of this pressure by means of mechanisation has only substituted a scarcer source of input for the more abundant input of solar radiation: Machinery, chemical fertilisers and pesticides all rely on mineral resources for their operation, rendering modern agriculture – and the industrialised food processing and distribution systems associated with it – almost as dependent on earth's mineral stock as the industrial sector has always been.

From that point on, he predicts, ever deepening scarcities will cause widespread misery, aggravate social conflict throughout the globe, and intensify man's economic struggle to work and earn a livelihood.

[4]: 21 ... Population pressure and technological progress bring ceteris paribus the career of the human species nearer to its end only because both factors cause a speedier decumulation of its dowry [of mineral resources].

"[81]: 105 Georgescu-Roegen's followers and interpreters have since been discussing the existential impossibility of allocating earth's finite stock of mineral resources evenly among an unknown number of present and future generations.

Daly argues that this steady-state economy is both necessary and desirable in order to keep human environmental impact within biophysical limits (however defined), and to create more allocational fairness between present and future generations with regard to mineral resource use.

Herman Daly on his part has readily accepted his teacher's judgement on this subject matter: In order to compensate for the principle of diminishing returns in mineral resource extraction, an ever greater share of capital and labour in the economy will gradually have to be transferred to the mining sector, thereby skewing the initial structure of any steady-state system.

This technology propelled the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the second half of the 18th century, whereby man's economy has been thrust into a long, never-to-return overshoot-and-collapse trajectory with regard to the earth's mineral stock.

The fact that solar collectors of various kinds had been in operation on a substantial scale for more than a century without providing a breakthrough in energy efficiency brought Georgescu-Roegen to the conclusion that no Promethean recipe was yet around in the world in his day.

Hence, a lot of material equipment is needed as inputs at the surface of the earth to collect, concentrate and (when convenient) store or transform the radiation before it can be put to use on a larger industrial scale.

Georgescu-Roegen stressed the point that even with the proliferation of solar collectors throughout the surface of the globe, or the advent of fusion power, or both, any industrial economy will still depend on a steady flow of material resources extracted from the crust of the earth, notably metals.

[31]: 148f [53]: 196f [27][14]: 238 In his last published article on the subject matter before his death, Georgescu-Roegen recollected his encouragement when he had once earlier come across the concept of 'matter dissipation' used by German physicist and Nobel Prize laureate Max Planck to account for the existence of irreversible physical processes where no simultaneous transformation of energy was taking place.

Modelling a possible future economic system for mankind, Robert Ayres has countered Georgescu-Roegen's position on the impossibility of complete and perpetual recycling of material resources.

In this spaceship economy, all waste materials will be temporarily discarded and stored in inactive reservoirs – or what he calls 'waste baskets' – before being recycled and returned to active use in the economic system at some later point in time.

In effect, complete and perpetual recycling of material resources will be possible in a future spaceship economy of this kind specified, thereby rendering obsolete Georgescu-Roegen's proposed fourth law of thermodynamics, Ayres submits.