Nicholas M. Nolan

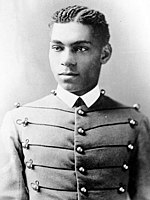

He was the commanding officer of Henry O. Flipper in 1878, the first African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Union "horse soldiers" became cavalry troopers under this tough regimen and proved adept, dismounted and mounted on horseback, with their carbines, pistols, and sabers, and confident under their battle-proven leaders.

[2] On July 3, 1863, reports of a slow moving Confederate wagon train in the vicinity of Fairfield, Pennsylvania, attracted the attention of newly commissioned Union Brigadier General Wesley Merritt of the Reserve Brigade, First Division, Cavalry Corps.

Nolan's troops and others threw back a mounted charge of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, just as the Confederate Chew's Battery unlimbered and opened fire on the Federal cavalrymen.

General "Grumble" Jones, outnumbering the Union forces by more than 2 to 1, pursued the retreating Federals for three miles to the Fairfield Gap, but was unable to eliminate his quarry.

Small groups of the 6th Cavalry," ... reformed several miles from the field of action by Lt. Louis H. Carpenter," harassed the Virginia troopers giving the impression of the vanguard of a much larger force.

Private George Crawford Platt, later Sergeant, an Irish immigrant serving in Carpenter's Troop H, was awarded the Medal of Honor on July 12, 1895, for his actions that day at Fairfield.

His citation reads, "Seized the regimental flag upon the death of the standard bearer in a hand-to-hand fight and prevented it from falling into the hands of the enemy."

He engaged many Native American tribes, dealt with many types of renegades and helped explore vast areas of uncharted territory from Texas to Arizona.

[18] After his extended leave, Nolan, as a first lieutenant in the Regular U.S. Army, volunteered for cavalry duty with "Negro Troops" that were being raised on the frontier.

Carpenter was dispatched to Philadelphia to recruit non-commissioned officers in late summer and fall of 1866 and would officially receive Company H on July 21, 1867.

Nolan wrote to the Adjutant General's Office in Washington, D.C., and correspondence included references to the Secretary of War and the President of the United States.

[1] The 10th Regimental headquarters remained at Fort Gibson until March 31, 1869, when they moved to Camp Wichita, Indian Territory (now the state of Oklahoma).

[23] While Carpenter, with Troops H and L, patrolled the area aggressively, Nolan provided a mobile interior defense against the prairie fires being set upwind of the settlement and at different points.

This was also known as the Staked Plains Horror and was a tragic series of events in the hot dry Llano Estacado region of north-west Texas and eastern New Mexico.

[24] Another important factor would include Quanah Parker, a Kwahada leader, who rode into the situation with an Army pass, to seek out the raiding Indians and to convince them to return to the reservation.

Parker and the primary buffalo hunter scout Jose Piedad Tafoya, a former Comanchero, would come to an understanding despite previous difficulties between the two.

[6] The "Army and Navy Journal" dated September 15, 1877, has an article called, "A Fearful march on the Staked Plains" taken from a report of Nicholas M. Nolan.

Miss Mollie Dwyer, Anne's sister arrived shortly after Troop A moved to Fort Elliott in Texas in early 1879.

[20][28] Colonel Grierson, commander of the 10th Cavalry, traversed the hot Chihuahuan Desert and then the narrow valleys of the Chinati Mountains, reaching Rattlesnake Springs on the morning of August 6, 1880.

With the hostile Apaches in their sights appearing ready to bolt, the soldiers did not wait and opened fire on their own initiative; Victorio's men scattered and withdrew out of carbine range.

Stunned by the presence of such a strong force but in desperate need of water, Victorio repeatedly charged the cavalrymen in attempts to reach the spring.

[29] On August 7, Carpenter, with Captain Nolan as second in command, and three companies of troopers headed out to Sulfur Springs to deny that source of water to the Apaches.

In the early light of day, Victorio saw a string of wagons rounding a mountain spur to the southeast and about eight miles distant, crawling onto the plain.

The Apache attack disintegrated as the warriors fled in confusion to the southwest to rejoin Victorio's main force as it moved deeper into the Carrizo Mountains.

Nolan sent out patrols while Carpenter's attack scattered the Indian guards while the troopers secured 25 head of cattle, provisions and several pack animals.

[29] On October 14, 1880, a sharpshooter of the Mexican Army ended Victorio's life at Cerro Tres Castillos, in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico.

[1] On October 24, 1883, while en route to Holbrook in Navajo County he suffered an "apoplexy" event that was later called "brain consumption" in the official report.

On the same day, Major Nicholas M. Nolan was buried in the San Antonio National Cemetery[1] He lies at rest in section A site 53 near the flagpole that flies the flag of his adopted country.

[31] His second wife, Annie E. Dwyer died on July 11, 1907, and is interred at Arlington National Cemetery as the "Widow of Major Nicholas M. Nolan 3rd U S Cavalry.