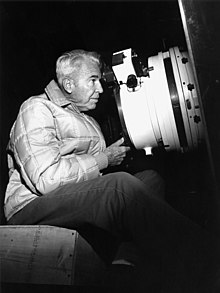

Nicholas U. Mayall

After obtaining his doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley, Mayall worked at the Lick Observatory, where he remained from 1934 to 1960, except for a brief period at MIT's Radiation Laboratory during World War II.

His father permitted him to use his car, a Moline Knight, to transport the club members up the dirt and gravel winding mountain road leading to the observatory.

Mayall generally did well at university, and was eventually elected to the Sigma Xi and Phi Beta Kappa honor societies.

Eventually Mayall discovered that he greatly enjoyed astronomy, and decided upon a course of graduate level study followed by a career as a research scientist.

However, he took a hiatus from pursuing his advanced degree and went to work as a human computer at the Mount Wilson Observatory from 1929 to 1931, where he assisted prominent astronomers including Edwin Hubble, Paul W. Merrill, and Milton L.

His thesis topic, suggested by Hubble, was to count the number of galaxies per unit area on the sky as a function of position on direct plates taken with the Crossley reflector at Lick.

[21][22] While working on his thesis, Mayall had an idea of designing a small, fast slitless spectrograph,[23] optimized for nebulae and galaxies.

Mayall's thesis advisor, William Hammond Wright, and the then head of the Lick stellar spectroscopy program, Joseph Haines Moore, encouraged him to develop his spectrograph.

The device was constructed by the Lick Observatory's own workshop, and proved to be more efficient for extended, low-surface-brightness objects, particularly in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, thus confirming the expectations of Mayall.

Instead, he began his career at Lick, which was afforded by the number two janitor resigning and Mayall being given a one-year position as observing assistant with janitorial duties limited to maintaining the darkrooms and keeping instrument rooms clean.

They lived in a small apartment that was part of the little astronomy village on the Mount Hamilton summit, where all Lick astronomers resided at that time.

[32] In 1941, together with Arthur Wyse and Lawrence Aller, Mayall studied the rotation of nearby galaxies and found that there was much matter that was too faint to be observed, but which could be detected by way of its gravitational effect.

[2][35] After the United States entered World War II, Mayall accepted a position at the MIT Radiation Laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts to work on radar development.

However, the climate of Massachusetts was unlike that of California, which he and his family were accustomed to, and in the middle of 1943 he arranged a transfer to the Pasadena Mount Wilson Observatory offices.

Mayall was adept at working with the small Crossley, but understood that it could never really stand up to a competing telescope that collected nine times the amount of light.

Agitated by the refusal, Sproul changed his stance and told the regents that they had to find a way to raise money for a new telescope once the war ended.

Wright and Joseph H. Moore, interim wartime Lick director, imagined an 85-inch (2.2 m) or 90-inch (2.3 m) reflector based upon the funds proposed in the budget by Sproul.

Mayall and Gerald E. Kron sent a letter to Sproul representing the younger Lick staff members, in which they requested a meeting to discuss the kind of telescope to be built.

Adams and the executive officer of the 200-inch (5.1 m) project, John August Anderson, shared their experience, drawings and plans with the Lick design committee.

[40] During the long period of building the 120-inch (3.0 m) telescope, Mayall continued to use Lick's 36-inch (0.91 m) Crossley Reflector and focused his efforts on utilizing his slitless spectrograph, which was optimized for extended, low-surface-brightness clusters, galaxies, and nebulae.

His paper was key in demonstrating that the system of Milky Way globular clusters shares only slightly the galactic rotation found in the flattened disc of interstellar matter and young stars in our galaxy.

[46][47] Other research Mayall performed included the 20 year collaboration (formulated in 1935 by Hubble) with Milton Humason, to gather redshift values for all northern galaxies brighter than +13 visual magnitude.

[55] Mayall moved on from the University of California (after more than 25 years[37] progressing from student to astronomer), to become the second director of Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO).

The first director was Aden B. Meinel, who chose the site near Tucson at the 7,000-foot (2,100 m) Kitt Peak, and oversaw the building of its first telescope, the 84-inch (2.1 m) reflector which was completed in the spring of 1960.

However, the AURA board decided that Meinel was not well suited for the job and chose Mayall to replace him on October 1, 1960,[57] even though he had no previous administrative experience.