Nidal Hasan

[25] According to The Washington Post, Hasan made a presentation titled "The Quranic World View as It Relates to Muslims in the U.S. Military" during his senior year of residency at WRAMC; it was not well received by some attendees.

[26] He suggested the U.S. Department of Defense "should allow Muslims [sic] Soldiers the option of being released as 'Conscientious objectors' to increase troop morale and decrease adverse events.

[23] However, an Army spokesman did not confirm the relatives' statements;[35] with the deputy director of the American Muslim Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Council stating the reported harassment was "inconsistent" with their records.

[43] Faizul Khan, the former Imam of the Silver Spring mosque where Hasan prayed several times a week, said he was "a reserved guy with a nice personality.

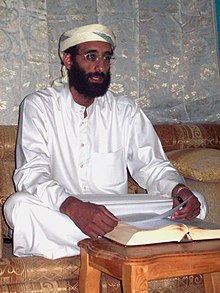

[46] Eleven months prior to the shootings, in December 2008, federal intelligence officials captured a series of e-mail exchanges between Al-Awlaki and Hasan.

[50][51][52] After the shootings, the Yemeni journalist Abdulelah Hider Shaea interviewed al-Awlaki in November 2009 about their exchanges, and discussed their time with a Washington Post reporter.

"[53] In October 2008, Charles Allen, US Undersecretary of Homeland Security for Intelligence and Analysis, warned al-Awlaki "targets US Muslims with radical online lectures encouraging terrorist attacks from his new home in Yemen".

"[56] The NEFA Foundation says, on December 23, 2008, six days after he said Hasan first e-mailed him, al-Awlaki wrote on his blog: "The bullets of the fighters of Afghanistan and Iraq are a reflection of the feelings of Muslims toward America.

[47][66] A review of Hasan's computer and e-mail accounts show visits to Internet sites espousing radical Islamist ideas, according to a press-release from an anonymous government agent.

[68] Days before his attacks on Fort Hood in 2009, Hasan asked his supervisors and Army legal advisers how to handle reports of soldiers' deeds in Afghanistan and Iraq that disturbed him.

Hasan told a local store owner he was stressed about his imminent deployment to Afghanistan since his work as a psychiatrist might require him to fight or kill fellow Muslims.

[84] To save his life, Hasan was hospitalized in the intensive care unit at Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas.

"[103] The prosecutors filed a memo on April 28, 2010, stating the "aggravating factor" necessary for pursuit of the death penalty will be satisfied if Hasan is found guilty of more than one murder.

[107] On November 18, Colonel James L. Pohl, investigating officer for the Article 32 hearing, recommended Hasan be court-martialed and face the death penalty.

Hasan notified Gross he had released John Galligan, his civilian attorney during previous court appearances, choosing to be represented by three military lawyers.

Lieutenant Colonel Kris Poppe, Hasan's lead attorney, said the request to delay the trial was "purely a matter of necessity of adequate time for pre-trial preparation".

[111] On April 10, 2012, Hasan's lawyers requested another continuance to move the trial start date from June to late October to investigate paperwork and evidence and interview witnesses.

The New York Times published remarks by Hasan from a mental health report supplied by the defendant's civil attorney John Galligan.

Earlier, he planned to call two defense witnesses: one a mitigation expert in capital murder cases, and the other a California university professor specializing in philosophy and religion.

[140] By August 27, the thirteen-member panel of jurors heard testimony from twenty-four victims and family members of those wounded and killed during the 2009 Fort Hood attacks against American armed forces.

[145] The panel also recommended Hasan forfeit his military pay and be dismissed from the Army, a separation for officers carrying the same consequences as a dishonorable discharge.

[151] In March 2010, Al Qaeda spokesman Adam Yahiye Gadahn praised Hasan, saying, although he was not a member of Al Qaeda, the Mujahid brother [...] shown us what one righteous Muslim with an assault rifle [sic] can do for his religion and brothers in faith [...] is a pioneer, a trail-blazer, and a role-model [...] and yearns to discharge his duty to Allah and play a part in the defense of Muslims against the savage, heartless, and bloody Zionist Crusader assault on our religion, sacred places, and homelands.

According to an anonymous source, Hasan was disciplined for "proselytizing about his Muslim faith with patients and colleagues" while at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS).

[157] The Dallas Morning News reported on November 17 that law enforcement officials suspected the attacks were triggered by the refusal of Hasan's superiors to process his requests seeking to have some of his patients prosecuted for war crimes based on statements they made during psychiatric sessions with him.

Webster was selected for the job due to, as Mueller stated, being "uniquely qualified" for such a review,[161] and the Webster Commission's press-release includes several recommendations including written policies to "[...] clarify the ownership of leads, integration of databases, and acquiring search capabilities for all relevant databases based on computational analysis of textual data to replace simple keyword searches [...]".

[165] Nancy Gibbs reported the cover story: "Hasan matched the classic model of the lone, strange, crazy killer: the quiet and gentle man who formed few close human attachments.

[167] On November 14, The New York Times stated, "Major Hasan may be the latest example of an increasingly common type of terrorist, self-radicalized with the help of the Internet, and wreaks havoc without support from overseas networks and without having to cross a border to reach his target.

"[168] Following his conviction and sentencing, Nidal Hasan was incarcerated at the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas to await execution.

Despite Army regulations banning personnel from facial hair, Hasan stopped shaving following the Fort Hood attacks in 2009 by citing his religious beliefs.

[176][177] The Israeli singer Eric Berman, in his album "Oh Pathetic Ridiculous Heart," composed the song "Not A Simple Story" following the background of the attacks.