Nihonium

Nihonium was first reported to have been created in experiments carried out between 14 July and 10 August 2003, by a Russian–American collaboration at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia, working in collaboration with the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, and on 23 July 2004, by a team of Japanese scientists at Riken in Wakō, Japan.

The confirmation of their claims in the ensuing years involved independent teams of scientists working in the United States, Germany, Sweden, and China, as well as the original claimants in Russia and Japan.

Experiments to date have supported the theory, with the half-lives of the confirmed nihonium isotopes increasing from milliseconds to seconds as neutrons are added and the island is approached.

[21] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

Cold fusion was pioneered by Yuri Oganessian and his team in 1974 at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Soviet Union.

Yields from cold fusion reactions were found to decrease significantly with increasing atomic number; the resulting nuclei were severely neutron-deficient and short-lived.

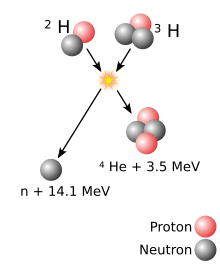

[56][57] Faced with this problem, Oganessian and his team at the JINR turned their renewed attention to the older hot fusion technique, in which heavy actinide targets were bombarded with lighter ions.

[56] In 1998, the JINR–LLNL collaboration started their attempt on element 114, bombarding a target of plutonium-244 with ions of calcium-48:[56] A single atom was observed which was thought to be the isotope 289114: the results were published in January 1999.

[9] A similar long-lived activity observed by the JINR team in March 1999 in the 242Pu + 48Ca reaction may be due to the electron-capture daughter of 287114, 287113; this assignment is also tentative.

The JINR–LLNL collaboration published its results in February 2004:[62] Four further alpha decays were observed, ending with the spontaneous fission of isotopes of element 105, dubnium.

[67] In June 2004 and again in December 2005, the JINR–LLNL collaboration strengthened their claim for the discovery of element 113 by conducting chemical experiments on 268Db, the final decay product of 288115.

[1][68] Both the half-life and decay mode were confirmed for the proposed 268Db which lends support to the assignment of the parent and daughter nuclei to elements 115 and 113 respectively.

[64] In November and December 2004, the Riken team studied the 205Tl + 70Zn reaction, aiming the zinc beam onto a thallium rather than a bismuth target, in an effort to directly produce 274Rg in a cross-bombardment as it is the immediate daughter of 278113.

[70] The Riken team then repeated the original 209Bi + 70Zn reaction and produced a second atom of 278113 in April 2005, with a decay chain that again terminated with the spontaneous fission of 262Db.

[67] In June 2006, the JINR–LLNL collaboration claimed to have synthesised a new isotope of element 113 directly by bombarding a neptunium-237 target with accelerated calcium-48 nuclei: Two atoms of 282113 were detected.

[64] The JWP did not accept the Riken team's claim either due to inconsistencies in the decay data, the small number of atoms of element 113 produced, and the lack of unambiguous anchors to known isotopes.

They were now joined by scientists from Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and Vanderbilt University, both in Tennessee, United States,[56] who helped procure the rare and highly radioactive berkelium target necessary to complete the JINR's calcium-48 campaign to synthesise the heaviest elements on the periodic table.

[67] In March 2010, the Riken team again attempted to synthesise 274Rg directly through the 205Tl + 70Zn reaction with upgraded equipment; they failed again and abandoned this cross-bombardment route.

[75] Although electricity prices had soared since the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, and Riken had ordered the shutdown of the accelerator programs to save money, Morita's team was permitted to continue with one experiment, and they chose their attempt to confirm their synthesis of element 113.

The recommendations were widely used in the chemical community on all levels, from chemistry classrooms to advanced textbooks, but were mostly ignored among scientists in the field, who called it "element 113", with the symbol of E113, (113), or even simply 113.

A survey of physicists determined that many felt that the Lund–GSI 2016 criticisms of the JWP report were well-founded, but it was also generally thought that the conclusions would hold up if the work was redone.

[81] IUPAC and IUPAP publicised the proposal of nihonium that June,[92] and set a five-month term to collect comments, after which the name would be formally established at a conference.

All isotopes with an atomic number above 101 undergo radioactive decay with half-lives of less than 30 hours: this is because of the ever-increasing Coulomb repulsion of protons, so that the strong nuclear force cannot hold the nucleus together against spontaneous fission for long.

Researchers in the 1960s suggested that the closed nuclear shells around 114 protons and 184 neutrons should counteract this instability, and create an "island of stability" containing nuclides with half-lives reaching thousands or millions of years.

The major reason for this is the spin–orbit (SO) interaction, which is especially strong for the superheavy elements, because their electrons move much faster than in lighter atoms, at velocities close to the speed of light.

[5] The melting and boiling points of nihonium have been predicted to be 430 °C and 1100 °C respectively, exceeding the values for indium and thallium, following periodic trends.

[110] Nihonium(I) is predicted to be more similar to silver(I) than thallium(I):[1] the Nh+ ion is expected to more willingly bind anions, so that NhCl should be quite soluble in excess hydrochloric acid or ammonia; TlCl is not.

[116]) Nihonium is expected to be able to gain an electron to attain this closed-shell configuration, forming the −1 oxidation state like the halogens (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, and astatine).

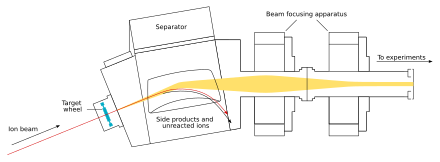

The nihonium atoms were synthesised in a recoil chamber and then carried along polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) capillaries at 70 °C by a carrier gas to the gold-covered detectors.

This experimental result for the interaction limit of nihonium atoms with a PTFE surface (−ΔHPTFEads(Nh) > 45 kJ/mol) disagrees significantly with previous theory, which expected a lower value of 14.00 kJ/mol.