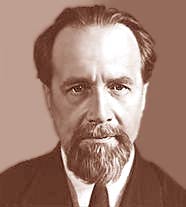

Nikolai Myaskovsky

After the death of his mother the family was brought up by his father's sister, Yelikonida Konstantinovna Myaskovskaya, who had been a singer at the Saint Petersburg Opera.

Early influences on Myaskovsky's emerging personal style were Tchaikovsky, strongly echoed in the first of his surviving symphonies (in C minor, Op.

3, 1908/1921), which was his Conservatory graduation piece, and Alexander Scriabin, whose influence comes more to the fore in Myaskovsky's First Piano Sonata in D minor, Op.

Myaskovsky graduated in 1911 and afterwards taught in Saint Petersburg, where he also developed a supplementary career as a penetrating musical critic, writing for the Moscow publication, "Muzyka.

[7] Called up during World War I, he was wounded and suffered shell-shock on the Austrian front, then worked on the naval fortifications at Tallinn.

[9] Myaskovsky himself served in the Red Army from 1917 to 1921; in the latter year he was appointed to the teaching staff of the Moscow Conservatory and membership of the Composers' Union.

Through his devotion to these forms, and the fact that he always maintained a high standard of craftsmanship, he was sometimes referred to as 'the musical conscience of Moscow'.

[11] In 1935, a survey made by CBS of its radio audience asking the question "Who, in your opinion, of contemporary composers will remain among the world's great in 100 years?"

placed Myaskovsky in the top ten along with Prokofiev, Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, Sibelius, Ravel, de Falla and Fritz Kreisler.

This symphony, sketched immediately after the disaster and premiered in Moscow on 24 October 1936, includes a big funeral march as its slow movement, and the finale is built on Myaskovsky's own song for the Red Air Force, 'The Aeroplanes are Flying'.

He does not deny himself a teasingly neurotic scherzo, as in his last two string quartets (that in the Thirteenth Quartet, his last published work, is frantic, and almost chiaroscuro but certainly contrasted) and the general paring down of means usually allows for direct and reasonably intense expression, as with the Cello Concerto (dedicated to and premiered by Sviatoslav Knushevitsky) and Cello Sonata No.

In 1947 Myaskovsky was singled out, with Shostakovich, Khachaturian and Prokofiev, as one of the principal offenders in writing music of anti-Soviet, 'anti-proletarian' and formalist tendencies.

Myaskovsky refused to take part in the proceedings, despite a visit from Tikhon Khrennikov inviting him to deliver a speech of repentance at the next meeting of the Composers' Union.

[12] He was only rehabilitated after his death from cancer in 1950, leaving an output of eighty-seven published opus numbers spanning some forty years and students with recollections.

[12] Myaskovsky never married and was shy, sensitive and retiring; Pierre Souvtchinsky believed that a "brutal youth (in military school and service in the war)" left him "a fragile, secretive, introverted man, hiding some mystery within.

[12] Stung by the many accusations in the Soviet press of "individualism, decadence, pessimism, formalism and complexity", Myaskovsky wrote to Asafyev in 1940, "Can it be that the psychological world is so foreign to these people?

[13] Shostakovich, who visited Myaskovsky on his deathbed, described him afterwards to the musicologist Marina Sabinina as "the most noble, the most modest of men".

[14] Mstislav Rostropovich, for whom Myaskovsky wrote his Second Cello Sonata late in life, described him as "a humorous man, a sort of real Russian intellectual, who in some ways resembled Turgenev".

His students included Aram Khachaturian, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Varvara Gaigerova, Vissarion Shebalin, Rodion Shchedrin, German Galynin, Andrei Eshpai, Alexei Fedorovich Kozlovsky, Alexander Lokshin, Boris Tchaikovsky, and Evgeny Golubev.

It has been said that the earlier music of Khachaturian, Kabalevsky and other of his students has a Myaskovsky flavor, with this quality decreasing as the composer's own voice emerges (since Myaskovsky's own output is internally diverse such a statement needs further clarification)[15]—while some composers, for instance the little-heard Evgeny Golubev, kept something of his teacher's characteristics well into their later music.

0" of Golubev's pupil Alfred Schnittke, released on CD in 2007, has striking reminiscences of Myaskovsky's symphonic style and procedures.

In the chaotic conditions prevailing at the breakup of the USSR, Svetlanov is rumoured to have had to pay the orchestral musicians himself in order to undertake the sessions.

To complicate matters, in July 2008, Warner Music France issued the entire 16-CD set, boxed, as volume 35 of their 'Édition officielle Evgeny Svetlanov'.