Chronology of the ancient Near East

Historical inscriptions and texts customarily record events in terms of a succession of officials or rulers: "in the year X of king Y".

More recent work by Vahe Gurzadyan has suggested that the fundamental eight-year cycle of Venus is a better metric.

The alternative major chronologies are defined by the date of the eighth year of the reign of Ammisaduqa, king of Babylon.

The most common Venus Tablet solutions (sack of Babylon) The following table gives an overview of the different proposals, listing some key dates and their deviation relative to the middle chronology, omitting the Supershort Chronology (sack of Babylon in 1466 BC): In the series, the conjunction of the rise of Venus with the new moon provides a point of reference, or rather three points, for the conjunction is a periodic occurrence.

[28][29] Some important examples: There are thirteen Egyptian New Kingdom lunar observations which are used to pin the chronology in that period by locking down the accession year of Ramsesses II to 1279 BC.

There are a number of issues with this including a) the regnal lengths for Neferneferuaten, Seti I, and Horemheb are actually not known with accuracy, b) where the observations occurred (Memphis is usually assumed), c) what day the observations were taken (two are known to be the 1st lunar day), and d) the Egyptian calendar for this period is not fully known, especially how intercalary months were handled.

[41] Since the Assyrian eponym list is accurate to one year only back to 1132 BC, ancient Near East chronology for the preceding century or so is anchored to Ramsesses II, based on synchronisms and the Egyptian lunar observations.

[43] Ancient observations of the heliacal rise of the planet Sirus (Sothic cycle) have also been used to try and date the Egyptian chronology.

[44] A number of attempts have been made to date Kassite Kudurru stone documents by mapping the symbols to astrononomical elements, using Babylonian star catalogues such as MUL.APIN with so far very limited results.

[49] Key documents like the Sumerian King List were repeatedly copied and redacted over generations to suit current political needs.

For this and other reasons, the Sumerian King List, once regarded as an important historical source, is now only used with caution, if at all, for the period under discussion here.

Additionally, our knowledge of the underlying languages, like Akkadian and Sumerian, has evolved over time, so a translation done now may be quite different from one done in AD 1900: there can be honest disagreement over what a document says.

The Assyrians in particular have a literary tradition of putting the best possible face on history, a fact the interpreter must constantly keep in mind.

[53] The Assyrian King List extends back to the reign of Shamshi Adad I (1809 – c. 1776 BC), an Amorite who conquered Assur while creating a new kingdom in Upper Mesopotamia.

Its purpose is to create a narrative of continuity and legitimacy for Assyrian kingship, blending in the kings of Amorite origin.

Kings also publicly recorded major deeds such as battles won, titles acquired, and gods appeased.

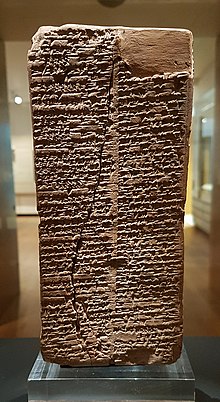

Cuneiform tablets were constantly moving around the ancient Near East, offering alliances (sometimes including daughters for marriage), threatening war, recording shipments of mundane supplies, or settling accounts receivable.

Most were tossed away after use as one today would discard unwanted receipts, but fortunately for us, clay tablets are durable enough to survive even when used as material for wall filler in new construction.

[66] We have some data sources from the classical period: Berossus, a Babylonian astronomer and historian born during the time of Alexander the Great wrote a history of Babylon which is a lost book.

[67] This book provides a list of kings starting with the Neo-Babylonian Empire and ending with the early Roman Emperors.

[68] [58] [69] Not having the stability of buried clay tablets, the records of the Hebrews have a great deal of ancient editorial work to sift through when used as a source for chronology.

However, the Hebrew kingdoms lay at the crossroads of Babylon, Assyria, Egypt and the Hittites, making them spectators and often victims of actions in the area during the 1st millennium.

Dendrochronology attempts to use the variable growth pattern of trees, expressed in their rings, to build up a chronological timeline.

[90][91][92] There is much evidence that the Bronze Age civilization of the Indus Valley traded with the Near East, including clay seals found at Ur III and in the Persian Gulf.

[94][95] In addition, if the land of Meluhha does indeed refer to the Indus Valley, then there are extensive trade records ranging from the Akkadian Empire until the Babylonian Dynasty I.

Goods from Greece made their way into the ancient Near East, directly in Anatolia and via the island of Cyprus in the rest of the region and Egypt.

A Hittite king, Tudhaliya IV, even captured Cyprus as part of an attempt to enforce a blockade of the Assyrians.

A large eruption, it would have sent a plume of ash directly over Anatolia and filled the sea in the area with floating pumice.

Archaeological remains date the eruption toward the end of the Late Minoan IA period (c. 1636–1527 BC) roughly comparable to the beginning of the New Kingdom in Egypt.