Nipmuc

[6] Their historic territory Nippenet, meaning 'the freshwater pond place', is in central Massachusetts and nearby parts of Connecticut and Rhode Island.

Many Nipmuc were held captive on Deer Island in Boston Harbor and died of disease and malnutrition, while others were executed or sold into slavery in the West Indies.

Backed by the colonial government, he established several "Indian plantations" or praying towns, where Native Americans were coerced to settle and be instructed in European customs and converted to Christianity.

In 1637, Roger Williams recorded the tribe as the Neepmuck, which derives from Nipamaug, 'people of the freshwater fishing place,' and also appears spelled as Neetmock, Notmook, Nippimook, Nipmaug, Nipmoog, Neepemut, Nepmet, Nepmock, Neepmuk, as well as modern Nipmuc(k).

Daniel Gookin (1612–1687), Superintendent to the Native Americans and assistant of Eliot, was careful to distinguish the Nipmuc (proper), Wabquasset, Quaboag, and Nashaway tribes.

'[19] The all-Indian Commission was established; it conferred state support for education, health care, cultural continuity, and protection of remaining lands for the descendants of the Wampanoag, Nipmuc and Massachusett tribes.

[21] The Commonwealth of Massachusetts also cited the continuity of the Nipmuc(k) with the historic tribe and commended tribal efforts to preserve their culture and traditions.

The state also symbolically repealed the General Court Act of 1675 that banned Native Americans from the City of Boston during King Philip's War.

The tribe, in conjunction with the National Congress of American Indians were against the construction of the sewage treatment plant on Deer Island in Boston Harbor where many graves were desecrated by its construction, and annually hold a remembrance service for members of the tribe lost over the winter during their internment during King Philip's War and protest against the destruction of Indian gravesites.

[23] On April 22, 1980, Zara Cisco Brough, landowner of Hassanamessit, submitted a letter of intention to petition for federal recognition as a Native American tribe.

On July 20, 1984, the BIA received the petition letter from the 'Nipmuc Tribal Council Federal Recognition Committee', co-signed by Zara Cisco Brough and her successor, Walter A. Vickers, of the Hassanamisco, and Edwin 'Wise Owl' W. Morse Sr. of the Chaubunagungamaug.

These early seafarers introduced several infectious diseases to which the Native Americans had no prior exposure, resulting in epidemics with mortality rates as high as 90 percent.

[7] As shown by the writings of Increase Mather, the colonists attributed the decimation of the Native Americans to God's providence in clearing the new lands for settlement, but they were accustomed to interpreting their lives in such religious terms.

[25] At the time of contact, the Nipmuc were a fairly large grouping, subject to more powerful neighbors who provided protection, especially against the Pequot, Mohawk and Abenaki tribes that raided the area.

Following is a list of Indian Plantations (Praying towns) associated with the Nipmuc:[28][29][30] Chaubunagungamaug, Chabanakongkomuk, Chaubunakongkomun, or Chaubunakongamaug Hassanamesit, Hassannamessit, Hassanameset, or Hassanemasset Magunkaquog, Makunkokoag, Magunkahquog, Magunkook, Maggukaquog or Mawonkkomuk Manchaug, Manchauge, Mauchage, Mauchaug, or Mônuhchogok Manexit, Maanexit, Mayanexit Nashoba Natick Okommakamesitt, Agoganquameset, Ockoocangansett, Ogkoonhquonkames, Ognonikongquamesit, or Okkomkonimset Packachoag, Packachoog, Packachaug, Pakachog, or Packachooge Quabaug, Quaboag, Squaboag Quinnetusset, Quanatusset, Quantiske, Quantisset, or Quatiske, Quattissick Wabaquasset, Wabaquassit, Wabaquassuck, Wabasquassuck, Wabquisset or Wahbuquoshish Wacuntuc, Wacantuck, Wacumtaug, Wacumtung, Waentg, or Wayunkeke Washacum or Washakim The Massachusetts Bay Colony passed numerous legislation against Indian culture and religion.

New laws were passed to limit the influence of the powwows, or 'shamans', and restricted the ability of non-converted Native Americans to enter colonial towns on the Sabbath.

The Native Americans that had already settled the Praying towns were interned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor over the winter where a great many perished from starvation and exposure to the elements.

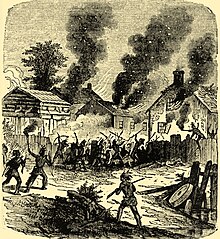

[32] The Nipmuc were major participants in the siege of Lancaster, Brookfield, Sudbury and Bloody Brook, all in Massachusetts,[33] and the tribe prepared thoroughly for conflict by forming alliances, and the group even had "an experienced gunsmith, a lame man, who kept their weapons in good working order.

[35] The Native Americans lost the war, and survivors were hunted down, murdered, sold into slavery in the West Indies or forced to leave the area.

With smaller numbers and landholdings, Indian autonomy was worn away by the time of the Revolutionary War, the remaining reserve lands were overseen by colony- and later state-appointed guardians that were to act on the Native Americans' behalf.

[41][42] The upheaval of the Indian Wars and growing mistrust of the Native Americans by the colonists lead to a steady trickle, and sometimes whole villages, that fled to increasingly mixed-tribe bands either northward to the Pennacook and Abenaki who were under the protection of the French or westward to join the Mahican at increasingly mixed settlements of Schagticoke or Stockbridge, the latter of which eventually migrated as far west as Wisconsin.

Rapid acculturation and intermarriage led many to believe the Nipmuc had simply just vanished, due to a combination of romantic notions of who the Native Americans were and to justify the colonial expansion.

[48] The children of such unions were accepted into the tribe as Native Americans, due to the matrilineal focus of Nipmuc culture, but to the eyes of their sceptical White neighbours, the increasingly Black phenotypes of some were seen to delegitimize their Indian identity.

[51] The turn of the century also saw active cultural and genealogical research by James L. Cisco and his daughter Sara Cisco Sullivan from the Grafton homestead, and worked closely with the remnants of other closely related tribes, such as Gladys Tantaquidgeon and the Fielding families of the Mohegan Tribe, Atwood L. Williams of the Pequot, and William L. Wilcox of the Narragansett.

Many local members of the tribe were called upon to help with the development of the Native American exhibit at Old Sturbridge Village, a 19th-century living museum built in the heart of former Nipmuc territory.