Plains Indians

Their historic nomadism and armed resistance to domination by the government and military forces of Canada and the United States have made the Plains Indian culture groups an archetype in literature and art for Native Americans everywhere.

The first group became a fully nomadic horse culture during the 18th and 19th centuries, following the vast herds of American bison, although some tribes occasionally engaged in agriculture.

The second group were sedentary and semi-sedentary, and, in addition to hunting bison, they lived in villages, raised crops, and actively traded with other tribes.

[1] Numerous Plains peoples hunted the American bison (or buffalo) to make items used in everyday life, such as food, cups, decorations, crafting tools, knives, and clothing.

Wars with the Ojibwe and Cree peoples pushed the Lakota (Teton Sioux) west onto the Great Plains in the mid- to late 17th century.

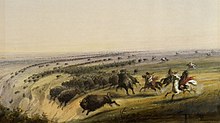

[7] The horse enabled the Plains Indians to gain their subsistence with relative ease from the seemingly limitless bison herds.

Riders were able to travel faster and farther in search of bison herds and to transport more goods, thus making it possible to enjoy a richer material environment than their pedestrian ancestors.

[9][8]: 432 The French explorer Claude Charles Du Tisne found 300 horses among the Wichita on the Verdigris River in 1719, but they were still not plentiful.

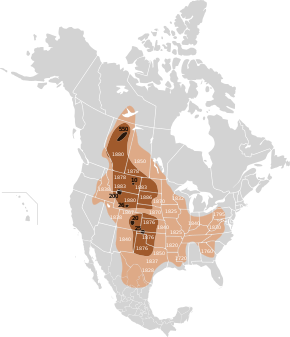

[8]: 429–437 By 1770, Plains horse culture was established, consisting of mounted bison-hunting nomads from Saskatchewan and Alberta southward nearly to the Rio Grande.

[13] On the northeastern Plains of Canada, the Indians were less favored, with families owning fewer horses, remaining more dependent upon dogs for transporting goods, and hunting bison on foot.

[14] The Lakota, also called Teton Sioux, enjoyed the happy medium between North and South and became a dominant Plains tribe by the mid-19th century.

At the same time, they occupied the heart of prime bison range which was also an excellent region for furs, which could be sold to French and American traders for goods such as guns.

[15] By the 19th century, the typical year of the Lakota and other northern nomads was a communal buffalo hunt as early in spring as their horses had recovered from the rigors of the winter.

In June and July the scattered bands of the tribes gathered together into large encampments, which included ceremonies such as the Sun Dance.

These gatherings afforded leaders to meet to make political decisions, plan movements, arbitrate disputes, and organize and launch raiding expeditions or war parties.

Beginning in the 1830s, the Comanche and their allies often raided for horses and other goods deep into Mexico, sometimes venturing 1,000 miles (1,600 km) south from their homes near the Red River in Texas and Oklahoma.

Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding through hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions.

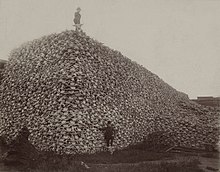

In 1875, General Philip Sheridan pleaded to a joint session of Congress to slaughter the herds, to deprive the Plains Indians of their source of food.

Armed conflicts intensified in the late 19th century between Native American nations on the plains and the U.S. government, through what were called generally the Indian Wars.

Comanche power peaked in the 1840s when they conducted large-scale raids hundreds of miles into Mexico proper, while also warring against the Anglo-Americans and Tejanos who had settled in independent Texas.

[28] The earliest farmers, the Southern Plains villagers were probably Caddoan speakers, the ancestors of the Wichita, Pawnee, and Arikara of today.

[citation needed] By the 1870s bison herds were depleted and beef, cereal grains, fats and starchy vegetables became more important in the diet of Plains Indians.

Honored warriors and leaders earn the right to wear war bonnets, headdresses with feathers, often of golden or bald eagles.

One of the most important gatherings for many of the Plains tribes is the yearly Sun Dance, an elaborate spiritual ceremony that involves personal sacrifice, multiple days of fasting and prayer for the good of loved ones and the benefit of the entire community.

[33] Certain people are considered to be wakan (Lakota: "holy"), and go through many years of training to become medicine men or women, entrusted with spiritual leadership roles in the community.

The marriage was turbulent and formally ended when Making Out Road threw Carson and his belongings out of her tepee (in the traditional manner of announcing a divorce).

Young men gained both prestige and plunder by fighting as warriors, and this individualistic style of warfare ensured that success in individual combat and capturing trophies of war were highly esteemed [39]: 20 The Plains Indians raided each other, the Spanish colonies, and, increasingly, the encroaching frontier of the Anglos for horses, and other property.

[40] The most renowned of all the Plains Indians as warriors were the Comanche whom The Economist noted in 2010: "They could loose a flock of arrows while hanging off the side of a galloping horse, using the animal as protection against return fire.

Battles between Indians often consisted of opposing warriors demonstrating their bravery rather than attempting to achieve concrete military objectives.

[43] The exception to that was raids into Mexico by the Comanche and their allies in which the raiders often subsisted for months off the riches of Mexican haciendas and settlements.

George Catlin , 1832