Nusaybin

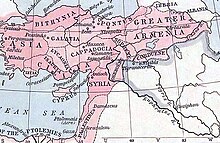

[7][8] Having been part of the Achaemenid Empire, in the Hellenistic period the settlement was re-founded as a polis named "Antioch on the Mygdonius" by the Seleucid dynasty after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

[7] Nisibis was a focus of international trade, and according to the Greek history of Peter the Patrician, the primary point of contact between Roman and Persian empires.

[7] The Roman soldier and Latin historian Ammianus Marcellinus described Nisibis, fortified with walls, towers, and a citadel, as "the strongest bulwark of the Orient".

[7] According to the Damascene monk John Moschus, the city's cathedral had five doors in the 7th century, and the monastic and later bishop of Harran, Symeon of the Olives, was recorded as having renewed several ecclesiastical buildings in the early period of Arab rule.

[7] However, besides the baptistery known as the Church of Saint Jacob (Mar Ya‘qub) and built in 359 by bishop Vologeses, little remains of ancient Nisibis, probably because of ruinous earthquake in 717.

Around the 1st century CE, Nisibis (Hebrew: נציבין, romanized: Netzivin) was the home of Judah ben Bethera, who founded a famous yeshiva there.

In 115 CE, it was captured by the Roman Emperor Trajan, for which he gained the name of Parthicus,[13] then lost to and regained from the Jews during the Diaspora Revolt.

According to the Expositio totius mundi et gentium bronze and iron were forbidden to be exported to the Persians, but for other goods, Nisibis was the site of substantial trade across the Roman–Persian frontier.

[7] Upon the death of Constantine the Great in 337 CE, the Sassanid Shah Shapur II marched against Roman held Nisibis with a vast army composed of cavalry, infantry and elephants.

[17] In 350 CE, while the Roman Emperor Constantius II was engaged in a civil war against the usurper Magnentius in the West, the Persians invaded and laid siege to Nisibis for the third time.

Unlike the first siege, as the walls fell, Persian assault troops immediately entered the breaches supported by war elephants.

The Romans, experts at close-quarter combat, and supported by arrows and bolts from the walls and towers checked the assault and a sortie from one of the gates forced the Persians to withdraw.

[18] The Roman historian of the 4th century, Ammianus Marcellinus, gained his first practical experience of warfare as a young man at Nisibis under the magister equitum, Ursicinus.

Ammianus lovingly calls Nisibis the "impregnable city" (urbs inexpugnabilis) and "bulwark of the provinces" (murus provinciarum).

Sozomen writes that when the inhabitants of Nisibis asked for help because the Persians were about to invade the Roman territories and attack them, Emperor Julian refused to assist them because they were Christianized, and he told them that he would not help them if they did not return to paganism.

Ephrem the Syrian, an Assyrian poet, commentator, preacher and defender of orthodoxy, joined the general exodus of Christians and re-established the school on more securely Roman soil at Edessa.

The expelled masters and pupils withdrew once more, back to Nisibis, under the care of Barsauma, who had been trained at Edessa, under the patronage of Narses, who established the statutes of the new school.

The two chief masters were the instructors in reading and in the interpretation of Holy Scripture, explained chiefly with the aid of Theodore of Mopsuestia.

Its rich library possessed a most beautiful collection of Nestorian works; from its remains Ebed-Jesus, Bishop of Nisibis in the 14th century, composed his celebrated catalogue of ecclesiastical writers.

From the middle of the 11th century onwards, it was subjected to Turkish raids and being threatened by the County of Edessa, being attacked and damaged by Seljuq forces under Tughril in 1043.

The city is described as a very prosperous one by the period's Arab geographers and historians, with imposing baths, walls, lavish houses, a bridge and a hospital.

[29] After the establishment of the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, Nusaybin lost over 60% of its population to the settlements there, most prominently Qamishli.

[32] Swedish historian David Gaunt visited the site to investigate its origins, but left after finding evidence of tampering.

Gaunt added that the death squad, named El-Hamşin (meaning "fifty men"), was headed by officer Refik Nizamettin Kaddur.

[39] On 13 November 2015, the town was placed under a curfew by the Turkish government, and Ali Atalan and Gülser Yıldırım, two elected members of the Grand National Assembly from the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP), began a hunger strike in protest.

[42] The Turkish state imposed eight successive curfews over several months and employed the use of heavy weapons in defeating the Kurdish militants, resulting in large swathes of Nusaybin being destroyed.

This rendered 30,000 citizens homeless and caused a mass evacuation of tens of thousands of residents to neighboring towns and villages.

Located to the east is Mount Judi, which people (including Muslims) consider to be the place where the ark of Nuh or Noah (who is regarded as a Nabi or Prophet in Abrahamic religions) came to rest.

[50] Fifteen of these (8 Mart, Abdulkadirpaşa, Barış, Devrim, Dicle, Fırat, Gırnavas, İpekyolu, Kışla, Mor-Yakup, Selahattin Eyyübi, Yenişehir, Yenituran and Zeynelabidin) form the central town (merkez) of Nusaybin.

Many of its Nestorian or Assyrian Church of the East and Jacobite bishops were renowned for their writings, including Barsumas, Osee, Narses, Jesusyab and Ebed-Jesus.