Njáls saga

[2] The saga deals with a process of blood feuds in the Icelandic Commonwealth, showing how the requirements of honor could lead to minor slights spiralling into destructive and prolonged bloodshed.

Insults where a character's manhood is called into question are especially prominent and may reflect an author critical of an overly restrictive ideal of masculinity.

The principal characters in the saga are the friends Njáll Þorgeirsson,[4] a lawyer and a sage, and Gunnar Hámundarson, a formidable warrior.

Gunnar's wife, Hallgerðr langbrók, instigates a feud that leads to the death of many characters over several decades including the killing by fire of the eponymous "Burnt Njáll".

The major events described in the saga are probably historical but the material was shaped by the author, drawing on oral tradition, according to his artistic needs.

Other suggested authors include Sæmundr's sons, Jón Loftsson, Snorri Sturluson, Einarr Gilsson, Brandr Jónsson and Þorvarðr Þórarinsson.

[10] Opinions on the historicity of the saga have varied greatly, ranging from pure fiction to nearly verbatim truth to any number of nuanced views.

[13] Njáls saga explores the consequences of vengeance as a defence of family honor by dealing with a blood feud spanning some 50 years.

The saga shows how even worthy people can destroy themselves by disputes and demonstrates the tensions in the Icelandic Commonwealth which eventually led to its destruction.

Magnus Magnusson finds it "a little pathetic, now, to read how vulnerable these men were to calls on their honour; it was fatally easy to goad them into action to avenge some suspicion of an insult".

In his view, the course of events is foreordained from the moment Hrútr sees the thieves' eyes in his niece and until the vengeance for Njáll's burning is completed to the southeast in Wales.

In this way, Laxness believed that Njáls saga attested to the presence of a "very strong heathen spirit",[17] antithetical to Christianity, in 13th century Iceland.

[18] Magnus Magnusson wrote that "[t]he action is swept along by a powerful under-current of fate" and that Njáll wages a "fierce struggle to alter its course" but that he is nevertheless "not a fatalist in the heathen sense".

[15] Thorsteinn Gylfason rejects the idea that there is any fatalism in Njáls saga, arguing that there is no hostile supernatural plan which its characters are subject to.

We are shown Hrútur's exploits in Norway where he gains honour at court and in battle, but he ruins his subsequent marriage by becoming the lover of the Norwegian queen mother Gunnhildur.

Hallgerður charms a number of dubious characters into killing members of Njáll's household and the spirited Bergþóra arranges vengeance.

Þráinn brings back the malevolent Hrappur, the sons of Njáll and the noble Kári Sölmundarson, who marries their sister.

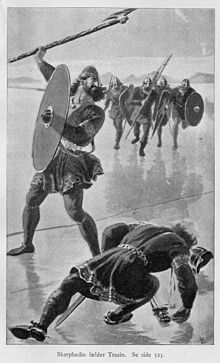

Skarphéðinn overtakes his brothers, leaps the river, and slides on the ice past Þráinn, splitting his skull in passing.

He sets the sons of Njáll against Höskuldur; the tragedy of the saga is that they are so susceptible to his promptings that they, with Mörður and Kári, murder him as he sows in his field.

[20][21] After some legal sparring, arbitrators are chosen, including Snorri goði, who proposes a wergild of three times the normal compensation for Höskuldur.

Moved by this, all but Kári and Njáll's nephew Þorgeir reach a settlement, while everyone contributes to Ljótur's weregild, which in the end amounts to a quadruple compensation.

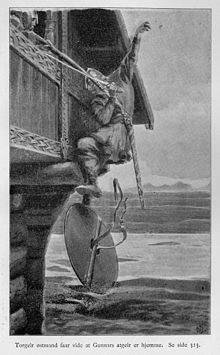

[24][25] The Red Romance Book, a collection of heroic tales and legends published in 1905 and lavishly illustrated by Henry Justice Ford, includes three stories based on the saga: The Slaying of Hallgerda's Husbands, The Death of Gunnar, and Njal's Burning.

These include Thomas Gray's The Fatal Sisters (1768), Richard Hole's The Tomb of Gunnar (1789), Jónas Hallgrímsson's Gunnarshólmi (1838), Sigurður Breiðfjörð's Rímur af Gunnari á Hlíðarenda (1860), Grímur Thomsen's Gunnarsríma (1890) and his Íslenzkar konur frá söguöldinni (1895), and Helen von Engelhardt's Gunnar von Hlidarendi (1909).

Dramatic works deriving from the saga's plot and characters include Gordon Bottomley's The Riding to Lithend (1909), Jóhann Sigurjónsson's Logneren/Lyga-Mörður (1917), Thit Jensen's Nial den Vise (1934), and Sigurjón Jónsson's Þiðrandi - sem dísir drápu (1950).

Embla Ýr Bárudóttir and Ingólfur Örn Björgvinsson's graphic novel adaptation of the saga, consisting of the four volumes Blóðregn, Brennan, Vetrarvíg, and Hetjan, was published in Iceland between 2003 and 2007.

Featured in the soundtrack is a song called "Brennu-Njálssaga," composed by the Icelandic new wave band, Þeyr with the collaboration of Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson.

In DreamWorks' animated series Dragons: Race to the Edge season 3 episode 3 a small excerpt from Njáls saga is chiseled into a sword and a wall in a cave using the Futhorc runic alphabet.

BBC Radio 3 broadcast The Saga of Burnt Njal, an audio adaptation by Hattie Naylor based on a translation by Benjamin Danielsson and directed by Gemma Jenkins, on 24 October 2021,[26] with Justin Salinger as "Njal", Christine Kavanagh as "Bergthora", Justice Ritchie as "Gunnar", Lisa Hammond as "Hattgerd", Jasmine Hyde as "Mord" and Salomé Gunnarsdottir as "The Voice of the Saga."

In numerous Shanghai magazines, the Chinese composer Nie Er went by the English name George Njal, after a character in the saga.

[31] The first printed edition of the saga, by Ólafur Ólafsson, based primarily on Reykjabók, with reference to Kálfalækjabók and Möðruvallabók, was published in Copenhagen in 1772.