Noah Webster

Noah Webster (October 16, 1758 – May 28, 1843) was an American lexicographer, textbook pioneer, English-language spelling reformer, political writer, editor, and author.

He was born into an established family, and the Noah Webster House continues to highlight his life and serves as the headquarters of the West Hartford Historical Society.

[9] At age six, Webster began attending a dilapidated one-room primary school built by West Hartford's Ecclesiastical Society.

His four years at Yale overlapped the American Revolutionary War and, because of food shortages and the possibility of a British invasion, many classes were held in other towns.

[13] Webster lacked clear career plans after graduating from Yale in 1779, later writing that a liberal arts education "disqualifies a man for business".

[15] While studying law under future U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth, Webster also taught full-time in Hartford—a grueling experience that ultimately proved unsustainable.

Later that year, he opened a small private school in western Connecticut, which initially succeeded but was eventually closed, possibly due to a failed romance.

[18] Turning to literary work as a way to overcome his losses and channel his ambitions,[19] he began writing a series of well-received articles for a prominent New England newspaper justifying and praising the American Revolution and arguing that the separation from Britain would be a permanent state of affairs.

[24] America sees the absurdities—she observes the kingdoms of Europe, disturbed by wrangling sectaries, or their commerce, population and improvements of every kind cramped and retarded, because the human mind like the body is fettered 'and bound fast by the chords of policy and superstition': She laughs at their folly and shuns their errors: She founds her empire upon the idea of universal toleration: She admits all religions into her bosom; She secures the sacred rights of every individual; and (astonishing absurdity to Europeans!)

she sees a thousand discordant opinions live in the strictest harmony ... it will finally raise her to a pitch of greatness and lustre, before which the glory of ancient Greece and Rome shall dwindle to a point, and the splendor of modern Empires fade into obscurity.Webster dedicated his Speller and Dictionary to providing an intellectual foundation for American nationalism.

In October 1787, he wrote a pamphlet entitled "An Examination into the Leading Principles of the Federal Constitution Proposed by the Late Convention Held at Philadelphia", published under the pen name "A Citizen of America".

He relied heavily on Rousseau's Social Contract while writing Sketches of American Policy, one of the earliest, widely-published arguments for a strong central government in America.

In December, he founded New York's first daily newspaper American Minerva, later renamed the Commercial Advertiser, which he edited for four years, writing the equivalent of 20 volumes of articles and editorials.

As a Federalist spokesman, Webster defended the administrations of George Washington and John Adams, especially their policy of neutrality between Britain and France, and he especially criticized the excesses of the French Revolution and its Reign of Terror.

When French ambassador Citizen Genêt set up a network of pro-Jacobin "Democratic-Republican Societies" that entered American politics and attacked President Washington, he condemned them.

As a result, he was repeatedly denounced by the Jeffersonian Republicans as "a pusillanimous, half-begotten, self-dubbed patriot", "an incurable lunatic", and "a deceitful newsmonger ... Pedagogue and Quack.

"[30] For decades, he was one of the most prolific authors in the new nation, publishing textbooks, political essays, a report on infectious diseases, and newspaper articles for his Federalist party.

From his own experiences as a teacher, Webster thought that the Speller should be simple and gave an orderly presentation of words and the rules of spelling and pronunciation.

Most people called it the "Blue-Backed Speller" because of its blue cover and, for the next one hundred years, Webster's book taught children how to read, spell, and pronounce words.

Several of those masterly addresses of Congress, written at the commencement of the late Revolution, contain such noble, just, and independent sentiments of liberty and patriotism, that I cannot help wishing to transfuse them into the breasts of the rising generation.

"Students received the usual quota of Plutarch, Shakespeare, Swift, and Joseph Addison, as well as such Americans as Joel Barlow's Vision of Columbus, Timothy Dwight's Conquest of Canaan, and John Trumbull's poem M'Fingal.

[40][41] Webster also included excerpts from Tom Paine's The Crisis and an essay by Thomas Day calling for the abolition of slavery in accord with the Declaration of Independence.

[44] Vincent P. Bynack (1984) examines Webster in relation to his commitment to the idea of a unified American national culture that would stave off the decline of republican virtues and solidarity.

Thus, the etymological clarification and reform of American English promised to improve citizens' manners and thereby preserve republican purity and social stability.

To evaluate the etymology of words, Webster learned twenty-eight languages, including Old English, Gothic, German, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, French, Dutch, Welsh, Russian, Hebrew, Aramaic, Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrit.

[46] However, his level of understanding for these languages was challenged with Charlton Laird claiming that Webster struggled with "elements of Anglo-Saxon grammar" and that he did "not recognize common words".

[53] Scholars have long seen Webster's 1844 dictionary to be an important resource for reading poet Emily Dickinson's life and work; she once commented that the "Lexicon" was her "only companion" for years.

Webster himself saw the dictionaries as a nationalizing device to separate America from Britain, calling his project a "federal language", with competing forces towards regularity on the one hand and innovation on the other.

To come north to preach and thus disturb our peace, when we can legally do nothing to effect this object, is, in my view, highly criminal and the preachers of abolitionism deserve the penitentiary.

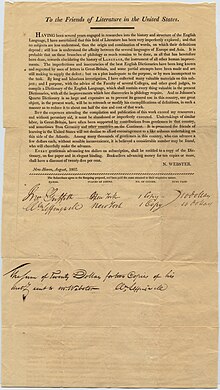

[64] Webster played a critical role lobbying individual states throughout the country during the 1780s to pass the first American copyright laws, which were expected to have distinct nationalistic implications for the young nation.