Noble savage

[4] In the philosophic debates of 17th-century Britain, the Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit was the Earl of Shaftesbury's ethical response to the political philosophy of Leviathan (1651), in which Thomas Hobbes defended absolute monarchy and justified centralized government as necessary because the condition of Man in the apolitical state of nature is a "war of all against all", for which reason the lives of men and women are "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" without the political organization of people and resources.

The European Hobbes gave, incorrectly, as example the Native Americans as people living in the bellicose state of nature that precedes tribes and clans organizing into the societies that compose a civilization.

[5] In many ways, the myth of the noble savage entails fantasies about the non-West that cut to the core of the conversation in the social sciences about Orientalism, colonialism and exoticism.

Very rare for so numerous a population is adultery [...] No one in Germany laughs at vice, nor do they call it the fashion to corrupt and to be corrupted.The 12th-century Andalusian allegorical novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan developed the idea through its noble savage titular protagonist understanding natural theology in a tabula rasa existence without any education or contact with the outside world,[8] inspiring later Western philosophy and literature during Age of Enlightenment.

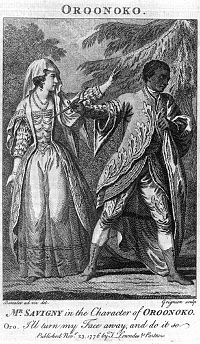

The stock character of the noble savage appears in the essay "Of Cannibals" (1580), about the Tupinambá people of Brazil, wherein the philosopher Michel de Montaigne presents "Nature's Gentleman", the bon sauvage counterpart to civilized Europeans in the 16th century.The first usage of the term noble savage in English literature occurs in John Dryden's stageplay The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards (1672), about the troubled love of the hero Almanzor and the Moorish beauty Almahide, in which the protagonist defends his life as a free man by denying a prince's right to put him to death, because he is not a subject of the prince: I am as free as nature first made man, Ere the base laws of servitude began, When wild in woods the noble savage ran.

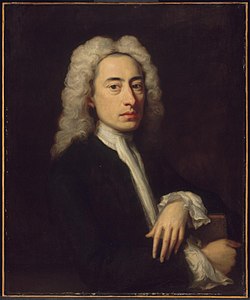

In English literature, British North America was the geographic locus classicus for adventure and exploration stories about European encounters with the noble savage natives, such as the historical novel The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 (1826), by James Fenimore Cooper, and the epic poem The Song of Hiawatha (1855), by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, both literary works presented the primitivism (geographic, cultural, political) of North America as an ideal place for the European man to commune with Nature, far from the artifice of civilisation; yet in the poem “An Essay on Man” (1734), the Englishman Alexander Pope portrays the American Indian thus: Lo, the poor Indian!

whose untutor'd mind Sees God in clouds, or hears Him in the wind; His soul proud Science never taught to stray Far as the solar walk or milky way; Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n, Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n; Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd, Some happier island in the wat'ry waste, Where slaves once more their native land behold, No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold!

To be, contents his natural desire; He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire: But thinks, admitted to that equal sky, His faithful dog shall bear him company.

To the English intellectual Pope, the American Indian was an abstract being unlike his insular European self; thus, from the Western perspective of "An Essay on Man", Pope's metaphoric usage of poor means "uneducated and a heathen", but also denotes a savage who is happy with his rustic life in harmony with Nature, and who believes in deism, a form of natural religion — the idealization and devaluation of the non-European Other derived from the mirror logic of the Enlightenment belief that "men, everywhere and in all times, are the same".

To the prosaic observer, the average Indian of the woods and prairies is a being who does little credit to human nature — a slave of appetite and sloth, never emancipated from the tyranny of one animal passion, save by the more ravenous demands of another.

In the Western U.S., those terms of address also referred to East Coast humanitarians whose conception of the mythical noble-savage American Indian was unlike the warrior who confronted and fought the frontiersman.

The protagonist is a wild man isolated from his society, whose trials and tribulations lead him to knowledge of Allah by living a rustic life in harmony with Mother Nature.

[15] As the Roman Catholic Bishop of Chiapas, the priest Bartolomé de las Casas witnessed the enslavement of the indigènes of New Spain, yet idealized them into morally innocent noble savages living a simple life in harmony with Mother Nature.

They are attached to a powerfully positive morality of valor and pride, one that would have been likely to appeal to early modern codes of honor, and they are contrasted with modes of behavior in the France of the wars of religion, which appear as distinctly less attractive, such as torture and barbarous methods of execution.

After all, following the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, the invented image of Charles IX shooting Huguenots from the Louvre Palace window did combine the established reputation of the King as a hunter, with a stigmatization of hunting, a cruel and perverted custom, did it not?

[20] The art historian Erwin Panofsky explains that: There had been, from the beginning of Classical speculation, two contrasting opinions about the natural state of man, each of them, of course, a "Gegen-Konstruktion" to the conditions under which it was formed.

... We value health, frugality, liberty, and vigor of body and mind: the love of virtue, the fear of the gods, a natural goodness toward our neighbors, attachment to our friends, fidelity to all the world, moderation in prosperity, fortitude in adversity, courage always bold to speak the truth, and abhorrence of flattery.

.The imperial politics of Western Europe featured debates about soft primitivism and hard primitivism worsened with the publication of Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651), by Thomas Hobbes, which justified the central-government regime of absolute monarchy as politically necessary for societal stability and the national security of the state: Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of War, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall.

In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.In the Kingdom of France, critics of the Crown and Church risked censorship and summary imprisonment without trial, and primitivism was political protest against the repressive imperial règimes of Louis XIV and Louis XV.

... [The Savage] looks with compassion on poor civilized man — no courage, no strength, incapable of providing himself with food and shelter: a degenerate, a moral cretin, a figure of fun in his blue coat, his red hose, his black hat, his white plume and his green ribands.

Everyone knows how Voltaire and Montesquieu used Hurons or Persians to hold up the [looking] glass to Western manners and morals, as Tacitus used the Germans to criticize the society of Rome.

But he observes that "the human race is what we wish to make it", that the felicity of Man depends entirely on the improvement of legislation, and ... his view is generally optimistic.Benjamin Franklin was critical of government indifference to the Paxton Boys massacre of the Susquehannock in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in December 1763.

Within weeks of the murders, he published A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County, in which he referred to the Paxton Boys as "Christian white savages" and called for judicial punishment of those who carried the Bible in one hand and a hatchet in the other.

[30] Like the Earl of Shaftesbury in the Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit (1699), Jean-Jacques Rousseau likewise believed that Man is innately good, and that urban civilization, characterized by jealousy, envy, and self-consciousness, has made men bad in character.

In Discourse on the Origins of Inequality Among Men (1754), Rousseau said that in the primordial state of nature, man was a solitary creature who was not méchant (bad), but was possessed of an "innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer.

[37]Rousseau proposes reorganizing society with a social contract that will "draw from the very evil from which we suffer the remedy which shall cure it"; Lovejoy notes that in the Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, Rousseau: ...declares that there is a dual process going on through history; on the one hand, an indefinite progress in all those powers and achievements which express merely the potency of man's intellect; on the other hand, an increasing estrangement of men from one another, an intensification of ill-will and mutual fear, culminating in a monstrous epoch of universal conflict and mutual destruction.

And the chief cause of the latter process Rousseau, following Hobbes and [Bernard] Mandeville, found, as we have seen, in that unique passion of the self-conscious animal — pride, self esteem, le besoin de se mettre au dessus des autres [the need to put oneself above others].

Precisely the two processes, which he described have ... been going on upon a scale beyond all precedent: immense progress in man's knowledge and in his powers over nature, and, at the same time, a steady increase of rivalries, distrust, hatred and, at last, "the most horrible state of war" ... [Moreover, Rousseau] failed to realize fully how strongly amour propre tended to assume a collective form ... in pride of race, of nationality, of class.

[38]In 1853, in the weekly magazine Household Words, Charles Dickens published a negative review of the Indian Gallery cultural program, by the portraitist George Catlin, which then was touring England.

[49][50] Anarcho-primitivists, such as the philosopher John Zerzan, rely upon a strong ethical dualism between Anarcho-primitivism and civilization; hence, "life before domestication [and] agriculture was, in fact, largely one of leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality, and health.