Non-sovereign monarchy

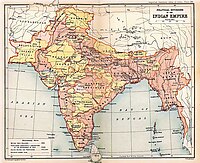

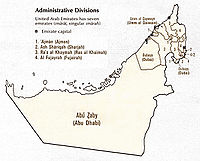

This situation can exist in a formal capacity, such as in the United Arab Emirates (in which seven historically independent emirates now serve as constituent states of a federation, the president of which is chosen from among the emirs), or in a more informal one, in which theoretically independent territories are in feudal suzerainty to stronger neighbors or foreign powers (the position of the princely states of India during British rule), and thus can be said to lack sovereignty in the sense that they cannot, for practical purposes, conduct their affairs of state unhampered.

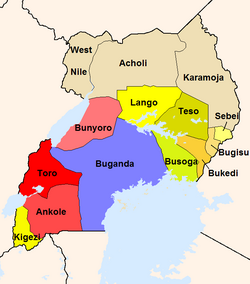

Sub-national monarchies also exist in a few states which are, in and of themselves, not monarchical, (generally for the purpose of fostering national traditions).

[2] In addition to this limited parliamentary role the kings play, the individual kingdoms' customary legal systems have some jurisdiction in areas of civil law.

Neger Sembilan itself consists of a number of sub-state monarchial chiefdoms/ The head of state of the entire federation is a constitutional monarch styled Yang di-Pertuan Agong (In English, "He who is made lord").

The Māori of New Zealand lived in the autonomous territories of numerous tribes, called iwi, before the arrival of British colonialists in the mid 19th century.

British encroachment on tribal lands continued, however, leading to the creation of the King Movement (Māori: Kīngitanga) in an attempt to foster strength through intertribal unity.

Before its defeat in the Land Wars, however, the King Movement wielded temporal authority over large parts of the North Island and possessed some of the features of a state, including magistrates, a state newspaper known as Te Hokioi, and government ministers (there was even a minister of Pākehā affairs [Pākehā being the Māori term for Europeans]).

[3] Today, though the monarch lacks political power, the position is invested with a great deal of mana (cultural prestige).

The monarchy is elective in theory, in that there is no official dynasty or order of succession, but hereditary in practice, as every monarch chosen by the tribal chiefs has been a direct descendant of Potatau Te Wherowhero (though not always the firstborn child of the previous ruler).

[4] The eighth and current Māori monarch is Queen Ngā Wai Hono i te Pō.

They have very little in the way of technical authority, but are in possession of real influence in practice due to their control of popular opinion within the various tribes.

In addition to this a number of them, such as the sultan of Sokoto and the Ooni of Ife, retain their spiritual authority as religious leaders of significant parts of the country in question's population.

The kingdom was a major regional power for most of the 19th century, but eventually was drawn into conflict with the expanding British Empire, and after a reduction in territory after defeat in the Anglo-Zulu War, lost its independence in 1887, when it was incorporated into the Natal Colony, and later the Union of South Africa.

It also empowers the national and provincial legislatures to formally establish houses for and councils of traditional leaders.

In 1853 the rulers signed a Perpetual Maritime Truce, and from that point onward delegated disputes between themselves to the British for arbitration (it is from this arrangement that the territory's former title, the "Trucial" States was derived).

are Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm al-Quwain.