Dispersion (optics)

[1] Sometimes the term chromatic dispersion is used to refer to optics specifically, as opposed to wave propagation in general.

All common transmission media also vary in attenuation (normalized to transmission length) as a function of frequency, leading to attenuation distortion; this is not dispersion, although sometimes reflections at closely spaced impedance boundaries (e.g. crimped segments in a cable) can produce signal distortion which further aggravates inconsistent transit time as observed across signal bandwidth.

[citation needed] For example, in fiber optics the material and waveguide dispersion can effectively cancel each other out to produce a zero-dispersion wavelength, important for fast fiber-optic communication.

However, in lenses, dispersion causes chromatic aberration, an undesired effect that may degrade images in microscopes, telescopes, and photographic objectives.

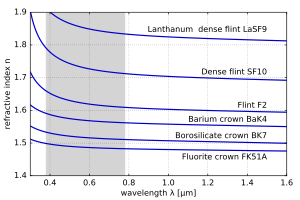

In general, the refractive index is some function of the frequency f of the light, thus n = n(f), or alternatively, with respect to the wave's wavelength n = n(λ).

The wavelength dependence of a material's refractive index is usually quantified by its Abbe number or its coefficients in an empirical formula such as the Cauchy or Sellmeier equations.

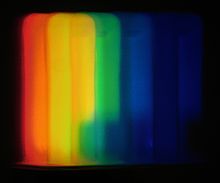

The most commonly seen consequence of dispersion in optics is the separation of white light into a color spectrum by a prism.

For visible light, refraction indices n of most transparent materials (e.g., air, glasses) decrease with increasing wavelength λ: or generally, In this case, the medium is said to have normal dispersion.

An everyday example of a negatively chirped signal in the acoustic domain is that of an approaching train hitting deformities on a welded track.

Group-velocity dispersion can be heard in that the volume of the sounds stays audible for a surprisingly long time, up to several seconds.

In practice, however, this approach causes more problems than it solves because zero GVD unacceptably amplifies other nonlinear effects (such as four-wave mixing).

Solitons have the practical problem, however, that they require a certain power level to be maintained in the pulse for the nonlinear effect to be of the correct strength.

The rate at which data can be transported on a single fiber is limited by pulse broadening due to chromatic dispersion among other phenomena.

In general, for a waveguide mode with an angular frequency ω(β) at a propagation constant β (so that the electromagnetic fields in the propagation direction z oscillate proportional to ei(βz−ωt)), the group-velocity dispersion parameter D is defined as[5] where λ = 2πc/ω is the vacuum wavelength, and vg = dω/dβ is the group velocity.

[6][7] These terms are simply a Taylor series expansion of the dispersion relation β(ω) of the medium or waveguide around some particular frequency.

Their effects can be computed via numerical evaluation of Fourier transforms of the waveform, via integration of higher-order slowly varying envelope approximations, by a split-step method (which can use the exact dispersion relation rather than a Taylor series), or by direct simulation of the full Maxwell's equations rather than an approximate envelope equation.

Spatial dispersion refers to the non-local response of the medium to the space; this can be reworded as the wavevector dependence of the permittivity.

is dielectric response (susceptibility); its indices make it in general a tensor to account for the anisotropy of the medium.

Fire is a colloquial term used by gemologists to describe a gemstone's dispersive nature or lack thereof.

Pulsars are spinning neutron stars that emit pulses at very regular intervals ranging from milliseconds to seconds.

This dispersion occurs because of the ionized component of the interstellar medium, mainly the free electrons, which make the group velocity frequency-dependent.