Norse rituals

These could be inherited or borrowed,[2] and although the great geographical distances of Scandinavia led to a variety of cultural differences, people understood each other's customs, poetic traditions and myths.

[5] Recent research suggests that great public festivals involving the population of large regions were not as important as the more local feasts in the life of the individual.

Even when the Christian influence is taken into account, they draw an image of a religion closely tied to the cycle of the year and the social hierarchy of society.

However, common cultural norms meant that it was normally the person with the highest status and the greatest authority (the head of the family or the leader of the village) who led the rituals.

Near Tissø, archaeologists have unearthed a complex consisting of, among other things, a central mead hall connected to a fenced area with a smaller building.

[20] The combination of religious festivals and markets has been common to most cultures through most of history, since a society where travel is difficult and communication limited uses such occasions to get several things done at the same time.

[22] Locally there were several kinds of holy places, usually marked by a boundary in the form of either a permanent stone barrier or a temporary fence of branches.

[31] Another word for hall, höll, was used to describe another kind of sacral building, not meant for habitation but dedicated to special purposes like holding feasts.

[36] There is general agreement that Gamla Uppsala was one of the last strongholds of heathen religion in central Sweden and that the religious centre there was still of great importance when Adam of Bremen wrote his account.

According to Adam, the temple at Uppsala was the centre for the national worship of the gods, and every nine years a great festival was held there where the attendance of all inhabitants of the Swedish provinces was required, including Christians.

It was built on an artificial plateau near the burial mounds from the Germanic Iron Age and was presumably a residence connected to the royal power, which was established in the area during that period.

Because of the limited knowledge about religious leaders there has been a tendency to regard the gothi and his female counterpart, the gyðja, as common titles throughout Scandinavia.

The term thul is related to words meaning recitation, speech and singing, so this religious function could have been connected to a sacral, maybe esoteric, knowledge.

There has been great disagreement about why, for instance, two bodies were found in the Oseberg tomb or how to interpret Ibn Fadlan's description of the killing of a female thrall at a funeral among the Scandinavian Rus on the Volga.

These rituals were connected to the change of status and transitions in life a person experiences, such as birth, marriage and death, and followed the same pattern as is known from other rites of passage.

[citation needed] In the Viking Age, people would pray to the goddesses Frigg and Freyja, and sing ritual galdr-songs to protect the mother and the child.

[57] The belief that deities were present during childbirth suggests that people did not regard the mother and the child as excluded from normal society as was the case in later, Christian, times and apparently there were no ideas about female biological functions being unclean.

[61] These conditions were reserved for the dominating class of freeholders (bóndi/bœndr), as the remaining parts of the population, servants, thralls and freedmen were not free to act in these matters but were totally dependent on their master.

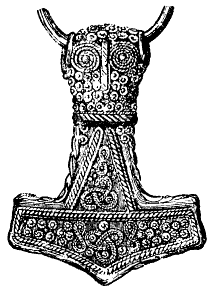

It is known that the goddess Vár witnessed the couple's vows, that a depiction of Mjolnir could be placed in the lap of the bride asking Thor to bless her, and that Freyr and Freyja were often called upon in matters of love and marriage, but there is no suggestion of a worship ritual.

On the first night the couple was led to bed by witnesses carrying torches, which marked the difference between legal marital relations and a secret extra-marital relationship.

The evidence of prehistoric openings in mounds may thus not indicate looting but the local community's efforts to retrieve holy objects from the grave, or to insert offerings.

Since the excavation of a mound was a time- and labour-consuming task which could not have happened unnoticed, religious historian Gro Steinsland and others find it unlikely that lootings of graves were common in prehistoric times.

Usually the graves were placed close to the dwelling of the family and the ancestors were regarded as protecting the house and its inhabitants against bad luck and bestowing fertility.

During Christianisation the attention of the missionaries was focused on the named gods; worship of the more anonymous collective groups of deities was allowed to continue for a while, and could have later escaped notice by the Christian authorities.

[66] It is hard to determine from the sources what the term meant in the Viking Age but it is known that Seid was used for divination and interpretation of omens for positive as well as destructive purposes.

Graves are the most common archaeological evidence of religious acts and they are an important source of knowledge about the ideas about death and cosmology held by the bereaved.

[74] However, in principle, material remains can only be used as circumstantial evidence to understanding Norse society and can only contribute concrete knowledge about the time's culture if combined with written sources.

At this feast, Haakon refused to eat the sacrificed horse meat that was served, and made the sign of the cross over his goblet instead of invoking Odin.

After this incident the king lost many of his supporters, and at the feast the following year, he was forced to eat the sacrificial meat and was forbidden to bless his beer with the sign of the cross.

For instance Margaret Clunies Ross has pointed out that the descriptions of rituals appearing in the sagas are recycled in a historicised context and may not reflect practice in pre-Christian times.