Viking Age

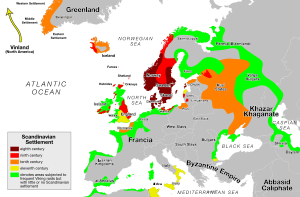

[4] Voyaging by sea from their homelands in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, the Norse people settled in the British Isles, Ireland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Normandy, and the Baltic coast and along the Dnieper and Volga trade routes in eastern Europe, where they were also known as Varangians.

[10] In the Lindisfarne attack, monks were killed in the abbey, thrown into the sea to drown, or carried away as slaves along with the church treasures, giving rise to the traditional (but unattested) prayer—A furore Normannorum libera nos, Domine, "Free us from the fury of the Northmen, Lord.

"[11] Three Viking ships had beached in Weymouth Bay four years earlier (although due to a scribal error the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dates this event to 787 rather than 789), but that incursion may have been a trading expedition that went wrong rather than a piratical raid.

During the Enlightenment and Nordic Renaissance, historians such as the Icelandic-Norwegian Thormodus Torfæus, Danish-Norwegian Ludvig Holberg, and Swedish Olof von Dalin developed a more "rational" and "pragmatic" approach to historical scholarship.

[18] Barrett considers that prior scholarship having examined causes of the Viking Age in terms of demographic determinism, the resulting explanations have generated a "wide variety of possible models".

[19] Bagge alludes to the evidence of demographic growth at the time, manifested in an increase of new settlements, but he declares that a warlike people do not require population pressure to resort to plundering abroad.

[24] In Western Europe, proto-urban centres such as those with names ending in wich, the so-called -wich towns of Anglo-Saxon England, began to boom during the prosperous era known as the "Long Eighth Century".

The second case is the internal "push" factor, which coincides with a period just before the Viking Age in which Scandinavia was undergoing a mass centralisation of power in the modern-day countries of Denmark, Sweden, and especially Norway.

The Viking colonisation of islands in the North Atlantic has in part been attributed to a period of favourable climate (the Medieval Climactic Optimum), as the weather was relatively stable and predictable, with calm seas.

These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island (Lindisfarne), by rapine and slaughter.

[43] The end of the Viking era in Norway is marked by the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030, in which Óláfr Haraldsson (later known as Olav the Holy), a fervent Christianiser who dealt harshly with those suspected of clinging to pagan cult, was killed.

[55] Their attacks became bigger and reached further inland, striking larger monastic settlements such as Armagh, Clonmacnoise, Glendalough, Kells, and Kildare, and also plundering the ancient tombs of Brú na Bóinne.

[60] During the next eight years the Vikings won decisive battles against the Irish, regained control of Dublin, and founded settlements at Waterford, Wexford, Cork, and Limerick, which became Ireland's first large towns.

[96] According to Thorsten Andersson, the Russian folk name Rus' ultimately derives from the noun roþer ('rowing'), a word also used in naval campaigns in the leþunger (Old Norse: leiðangr) system of organizing a coastal fleet.

[115] Castle building by the Slavs seems to have reached a high level on the southern Baltic coast in the 8th and 9th centuries, possibly explained by a threat coming from the sea or from the trade emporiums, as Scandinavian arrowheads found in the area indicate advances penetrating as far as the lake chains in the Mecklenburgian and Pomeranian hinterlands.

But the Vikings took advantage of the quarrels in the royal family caused after the death of Louis the Pious to settle their first colony in the south-west (Gascony) of the kingdom of Francia, which was more or less abandoned by the Frankish kings after their two defeats at Roncevaux.

The Vikings then moved another 60 miles down the Tuscan coast to the mouth of the Arno, sacking Pisa and then, following the river upstream, also the hill-town of Fiesole above Florence, among other victories around the Mediterranean (including in Sicily and Nekor (Morocco), North Africa).

The Vikings launched their campaigns from their strongholds in Francia into this realm of Muslim influence; following the coastline of the Kingdom of Asturias they sailed through the Gibraltar strait (known to them as Nǫrvasund, the 'Narrow Sound') into what they called Miðjarðarhaf, literally 'Middle of the earth' sea,[132] with the same meaning as the Late Latin Mare Mediterrāneum.

[135] In Irene García Losquiño's telling, these Vikings navigated their boats up the river Guadalquivir towards Išbīliya (Seville) and destroyed Qawra (Coria del Río), a small town about 15 km south of the city.

His account says a flotilla of about 80 Viking ships, after attacking Asturias, Galicia and Lisbon, had ascended the Guadalquivir to Išbīliya, and besieged it for seven days, inflicting many casualties and taking numerous hostages with the intent to ransom them.

[139] It was not a total victory for the emir's forces, but the Viking survivors had to negotiate a peace to leave the area, surrendering their plunder and the hostages they had taken to sell as slaves, in exchange for food and clothing.

According to the Arabist Lévi-Provençal, over time, the few Norse survivors converted to Islam and settled as farmers in the area of Qawra, Qarmūnâ, and Moron, where they engaged in animal husbandry and made dairy products (reputedly the origin of Sevillian cheese).

There is only brief mention in the historical record of this Viking army's attacks on south-eastern al-Andalus, including at al-Jazīra al-Khadrā (Algeciras), Ūriyūla, and the Juzur al-Balyār (جزُر البليار) (Balearic Islands).

The remaining vessels continued up the Atlantic coast and landed near (Pampeluna), called Banbalūna in Arabic,[143] where they took their emir Gharsīa ibn Wanaqu (García Iñiquez) prisoner until in 861 he was ransomed for 70,000 dinars.

[144] According to the Annales Bertiniani, Danish Vikings embarked on a long voyage in 859, sailing eastward through the Strait of Gibraltar then up the river Rhône, where they raided monasteries and towns and established a base in the Camargue.

[150][151] After a thirteen-day siege in which they plundered the surrounding countryside, the Vikings conquered al-Us̲h̲būna, but eventually retreated in the face of continued resistance by the townspeople led by their governor, Wahb Allah ibn Hazm.

[156] In about 986, the Norwegian Vikings Bjarni Herjólfsson, Leif Ericson, and Þórfinnr Karlsefni from Greenland reached Mainland North America, over 500 years before Christopher Columbus, and they attempted to settle the land they called Vinland.

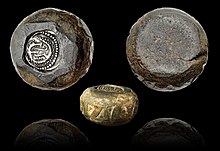

York was the centre of the kingdom of Jórvík from 866, and discoveries there (e.g., a silk cap, a counterfeit of a coin from Samarkand, and a cowry shell from the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf) suggest that Scandinavian trade connections in the 10th century reached beyond Byzantium.

As Scandinavian ships penetrated southward on the rivers of Eastern Europe to acquire financial capital, they encountered the nomad peoples of the steppes, leading to the beginning of a trading system that connected Russia and Scandinavia with the northern routes of the Eurasian Silk Road network.

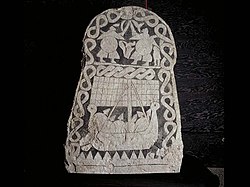

[176] Birgit Sawyer says her book The Viking-age Rune-stones aims to show that the corpus of runestones considered as a whole is a fruitful source of knowledge about the religious, political, social, and economic history of Scandinavia in the 10th and 11th centuries.